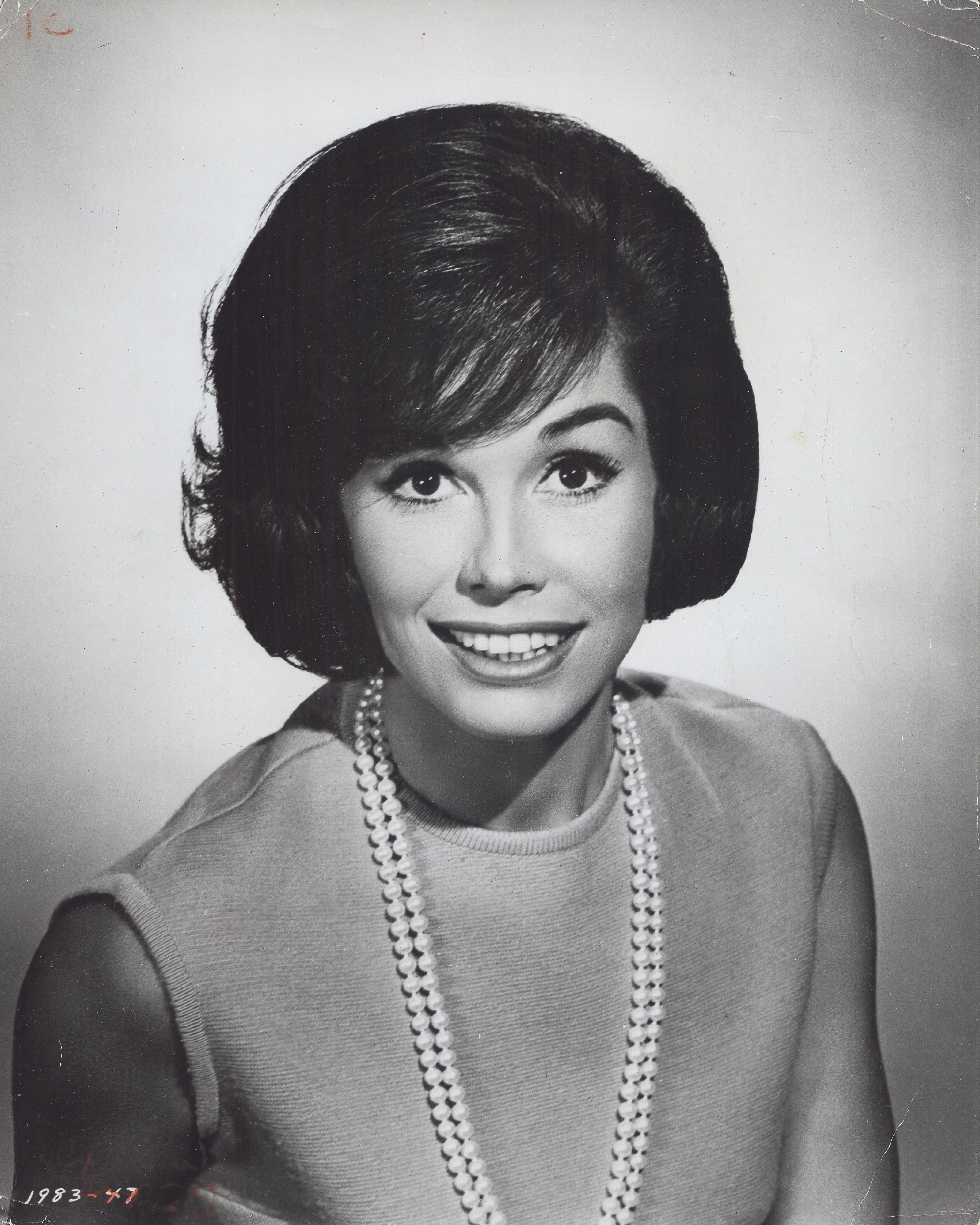

Mary Tyler Moore's complicated legacy

There's no question that Moore was crucial to the mainstreaming of feminism. But was she herself a feminist?

Mary Tyler Moore died of pneumonia at Connecticut's Greenwich Hospital on Wednesday. She was 80.

An advocate for diabetes research and animal rights activist in her latter years, Moore came to fame as Dick Van Dyke's wife Laura Petrie on The Dick Van Dyke Show, but she will probably be best remembered for playing Mary Richards, the winsome 30-something protagonist of The Mary Tyler Moore Show — a sitcom that won 29 Emmys and made "career women" palatable to audiences unused to the idea.

Moore dazzled with her smile. She made capris fashionable. She transformed TV history and helped mainstream the multi-camera sitcom. ("It seems to really be catching on as a technique," she says in this delightful 1977 interview with Bette Rogge.) And by endowing Mary Richards with her grace, charm, and verve, Moore helped audiences accept some modern truths: Mary Richards, assistant producer at WJM in Minneapolis, was the girl next door. And the girl next door was on the pill.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In Mary Richards, Moore inspired generations of women struggling to fit into the workplace — and trying to figure out how to reconcile some retrograde social expectations with the realities of modern living. Stars ranging from Oprah Winfrey to Katie Couric have cited the character as an inspiration. There's no question that Moore was crucial to the mainstreaming of feminism.

It's all the more interesting, then, that Moore's own feelings about all Mary Richards came to represent were complicated.

The feminist icon never quite took to the feminist label. She would declare herself a "libertarian centrist" in Parade magazine in 2009, and there are signs that she detected some condescension in response to her insistence on distinguishing herself from her most famous character. Asked in 1995 whether she resented reporters asking her about Mary Richards, she told The New York Times, "I think some of them may be trying to find some way to instruct, or to make a judgment about, or in some way set themselves above me."

Moore's life was shot through with tragedy: Born in 1936, she was neglected by her parents and struggled with alcoholism as an adult. She married at 18 and had her first and only child, Richard, at 19. He would die at 24 of an accidental self-inflicted gun wound. Her reflections on motherhood — and on how she considers her own career — likely stem from the pain from that loss.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"[T]ruth be told," she writes of her sitcom career in her 2009 memoir Growing Up Again, "work was my focus before, during, and after. If I had it to do over, I wouldn't have pursued a career while I had a little boy to care for. My heart breaks when I think of the times missed, times with him. How predictable that without awareness I emulated my mother's behavior toward me."

But though her memoirs are tinged with regret — and the express desire to have been a better mother and, one senses, a more conventional woman — Moore was every inch an artist. "I like to be challenged," she told Charlie Rose in 1995. "I like to not be totally familiar with areas that I'm going into anymore, because that satisfies the creative part of me."

Her first marriage (to Richard Meeker) lasted only six years, and she would later narrate it as a stage in her quest for self-determination. "When that marriage ended," she wrote, "I landed the role on The Dick Van Dyke Show; proudly I realized that I could take care of Richie and myself, at least economically. But emotionally I was not ready to take the helm and be the captain of the HMS Mary Tyler Moore." This was true: Within a year of her divorce, she'd married Grant Tinker, with whom she would start the MTM Company. "Despite, or maybe because of, the thrill of our accomplishments together," she would write, "I realized later that I had not been captain of my own ship — not even co-captain. I see now that it was a pattern that had long manifested itself in my personal relationships, my working life, my early marriages." Moore supposedly found that co-captaincy with her third and final husband, Dr. Robert Levine, 18 years her junior.

"Do you think Mary Richards was a trend setter?" Larry King once asked her. "Do you think she was a feminist?"

Moore's answer is telling. It is both "yes" and "no" — a version of progress more conciliatory, more willing to sacrifice than the movement Mary Richards would come to represent. But it suggests that she might have been closer to her character than even she thought:

She wasn't aggressive about it, but she surely was. The writers never forgot that. They had her in situations where she had to deal with it. There was the time where she found out that the man before her in that job was paid a good deal more money than she. And she stormed into Lou's office and said, explain this, will you? And he did and it didn't soothe her at all. He said, all right, how about this? Would it make you feel better if I told you that that man was married and had three children? And she says yes. And she gives in.

TV lost one of its greatest stars today. Let's toss a tam in the air in her honor.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

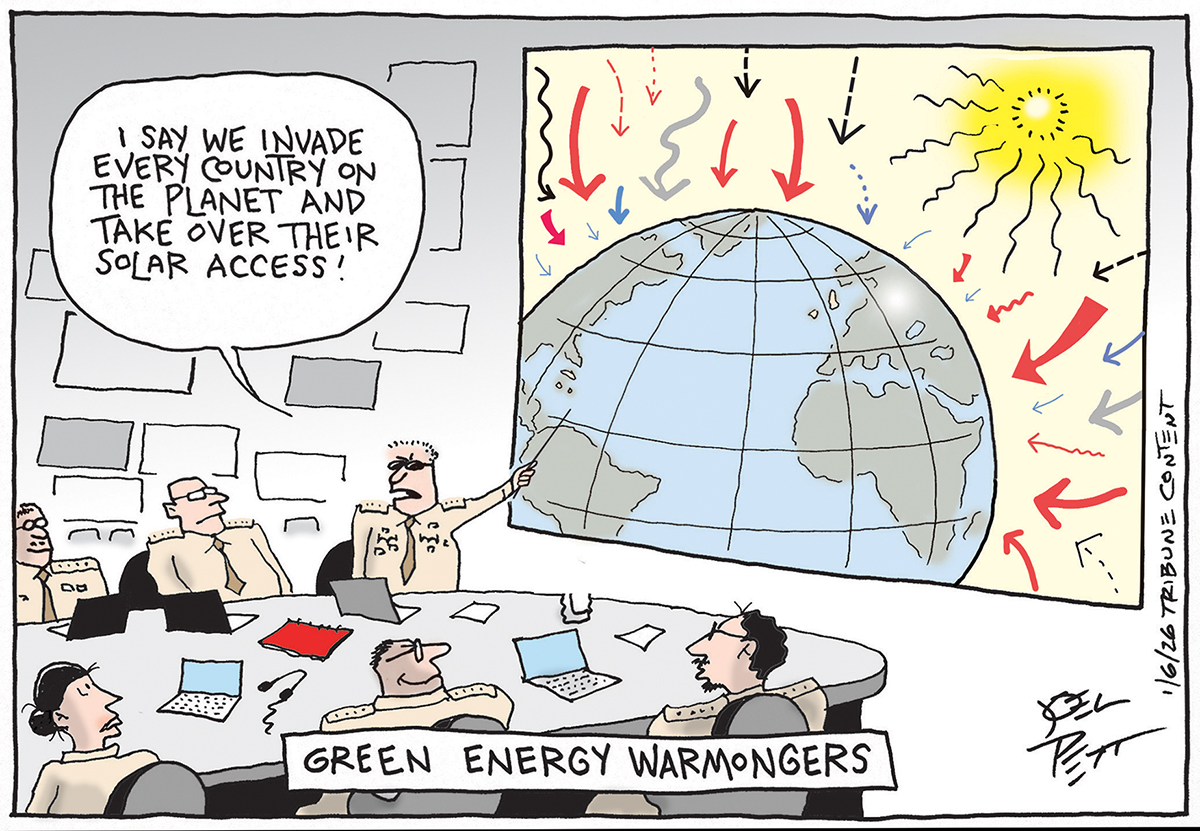

Political cartoons for January 11

Political cartoons for January 11Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include green energy, a simple plan, and more

-

The launch of the world’s first weight-loss pill

The launch of the world’s first weight-loss pillSpeed Read Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have been racing to release the first GLP-1 pill

-

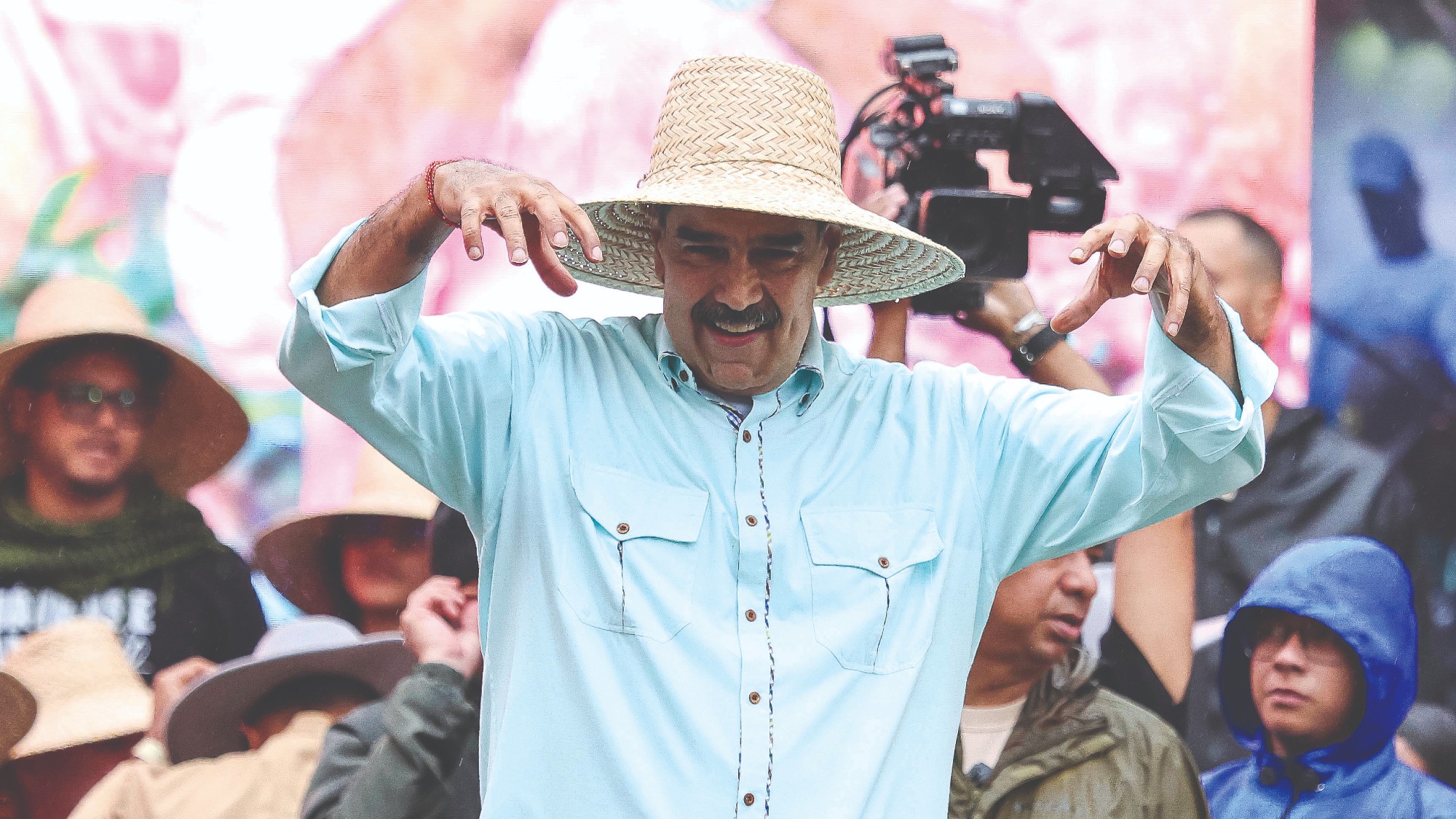

Maduro’s capture: two hours that shook the world

Maduro’s capture: two hours that shook the worldTalking Point Evoking memories of the US assault on Panama in 1989, the manoeuvre is being described as the fastest regime change in history

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.