It's time to retire the Oscars' 'Best Picture'

This vaunted category is absurdly blunt and meaninglessly broad

If you were paying attention to the Oscars in 1999, when Shakespeare in Love controversially won Best Picture over Saving Private Ryan, you know what's likely to happen when La La Land sweeps the Academy Awards on Sunday. (And it probably will: The Academy adores films about Hollywood's ability to make feel-good magic). A thousand thinkpieces will outline Moonlight's cinematic superiority to La La Land. We will read about Hidden Figures' greater historical import, about Fences' far more visceral honesty, about the ways Manchester by the Sea more experimentally blends humor with truly unfixable grief. Every one of these takes will be right. But they will all grant a flawed premise: that the Oscars can meaningfully judge something like Best Picture.

And in that, they will all be wrong.

To be useful, or informative, or meaningful, comparative contests should have some baseline similarities. The long jump measures who can jump farther. Even a sport that is less straightforward measures something clear: Olympic ice skaters compete to produce the most artistic and challenging routine. But film is more complex than any act of athleticism. Hidden Figures wants to make us remember. La La Land wants to make us forget. The former honors history. The second honors fantasy. These movies are not attempting similar things. What's the point of judging them as if they were?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If we hope to have a robust discussion about film as art, isn't it high time we developed better categories? Categories that acknowledge — as the industry has for decades — that genre exists?

The Hollywood Foreign Press Association recognized that need. The Golden Globes awards Best Picture trophies for "Drama" and for "Musical or Comedy," and has even established clear rules on how the modern spate of dramedies should fit into that spectrum. The SAG awards at least allow that the distinction between comedies and dramas exists in their television awards. But the Oscars — the dominant prestige event in an industry obsessed with categories and demographics and markets — still stubbornly insists on conveying an honor so absurdly blunt, so meaninglessly broad, that winning it says nothing. Or as much as a high school popularity contest tells you about the contents of human souls.

It's time to get rid of Best Picture.

Look, choosing a winner is always hard, even within a more narrowly defined genre. Which is better: An experimental and beautiful triptych about what growing up means for one gay black kid in South Florida, or a more conventional story about three unconventional adults who faced down sexism and racism and sent a man to space? Which movie was most creative with language: Manchester by the Sea, where people are frequently talking just out of frame, at a volume where you can just barely make it out and are invited (but not compelled) to overhear — echoing Lee's isolation? Or Fences, in which Troy's illiteracy only augments his oratorical jiujitsu? Or Arrival, where a linguist is radically transformed by the language she learns? Which of these is the most "important?" And how does "important" relate to "best?"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When you tack on an extra comparative layer — which is better, comedy or drama? — the exercise becomes not just moot but counterproductive. Comedy is an immensely important art form. It is. But when challenged to determine what's "best," it's awfully hard to defend comedy's intrinsic frivolity against drama, where people suffer and grieve and die. Shakespeare in Love was about a blond young white woman who cross-dressed to be taken seriously in early modern England and fell in love. It's romantic and a little bit silly. That this was considered "better" than a story about war — where far too many young men died — was an outrage in 1999. And there were plenty of reasons to object on artistic grounds. But the truth is, most didn't. Critics of Shakespeare in Love's win were less concerned with the acting, script, structure, or cinematography than they were by the Academy's choice of what subject matter they deemed "important" enough to honor.

We're likely to see a repeat of that this year, and it's a shame, because the film industry could so easily opt out of this meta version of the Hunger Games. It won't: A discussion about the business and the art that a less blunt instrument could make vital and illuminating will dissolve instead into a flood of defensive comparisons. But it could be different: Moonlight could walk away with Best Drama. La La Land could dance off with Best Musical or Comedy. And the Best Picture category would salute them from the In Memoriam reel, glad to be relieved.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

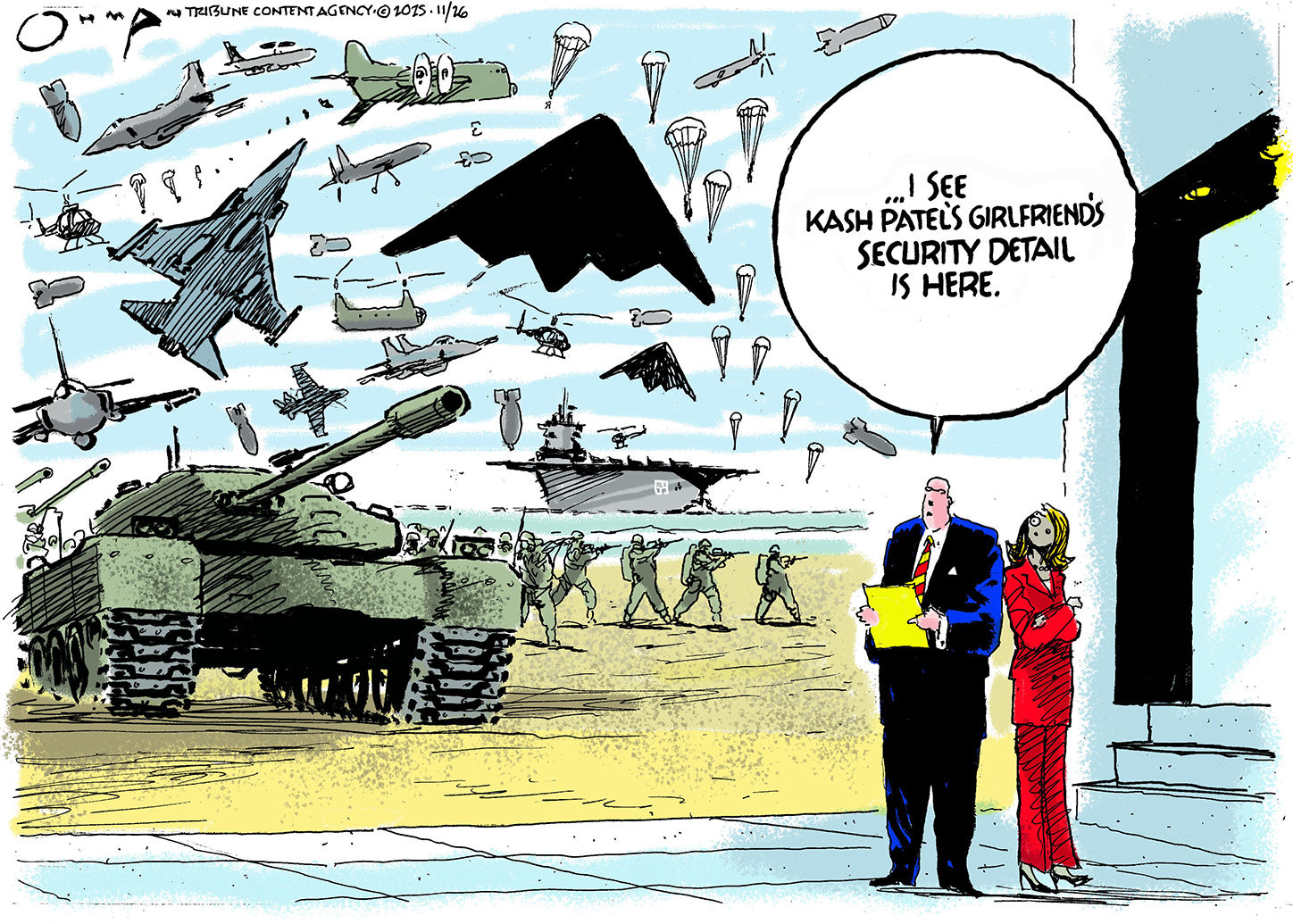

Political cartoons for November 29

Political cartoons for November 29Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include Kash Patel's travel perks, believing in Congress, and more

-

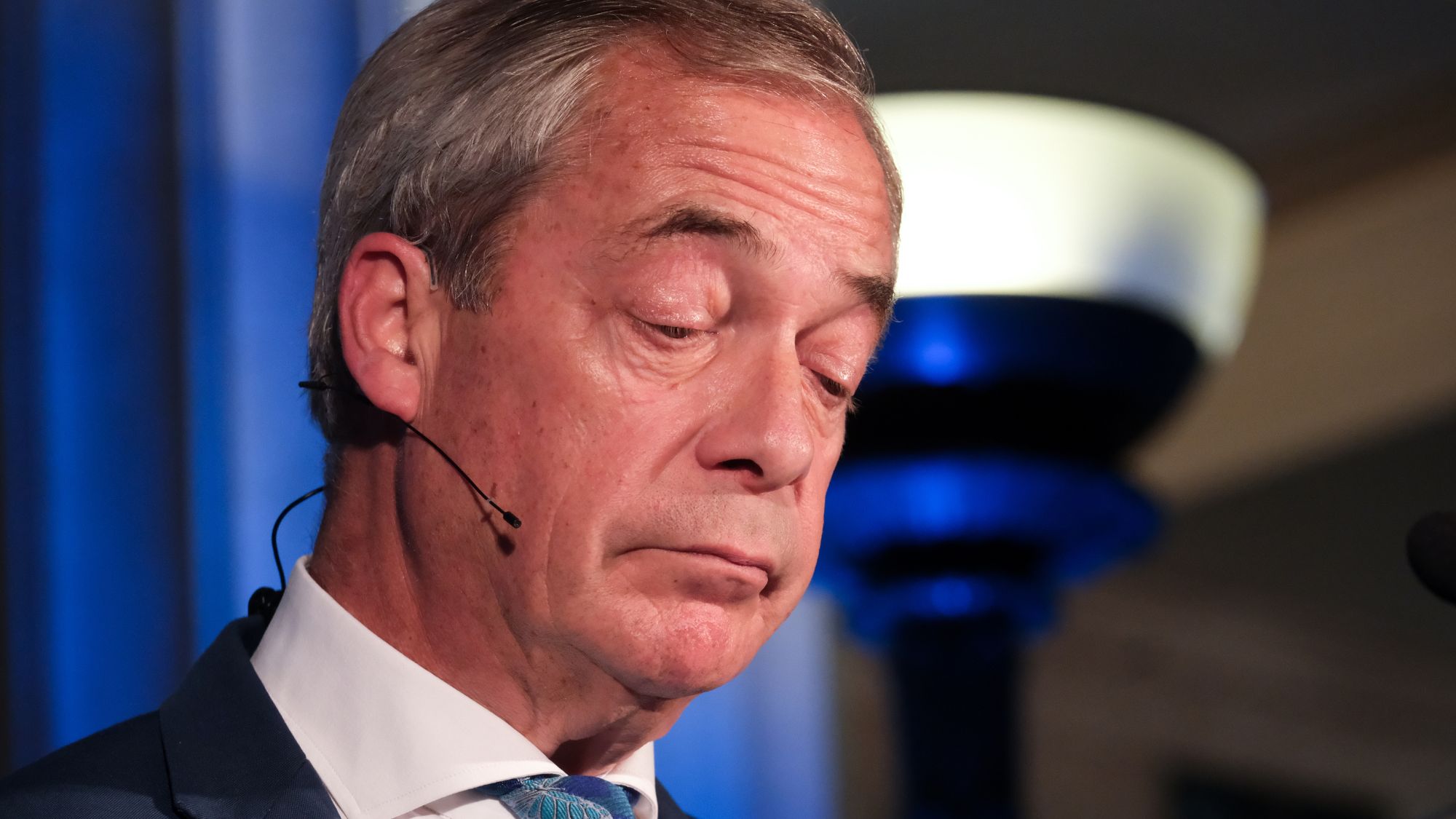

Nigel Farage: was he a teenage racist?

Nigel Farage: was he a teenage racist?Talking Point Farage’s denials have been ‘slippery’, but should claims from Reform leader’s schooldays be on the news agenda?

-

Pushing for peace: is Trump appeasing Moscow?

Pushing for peace: is Trump appeasing Moscow?In Depth European leaders succeeded in bringing themselves in from the cold and softening Moscow’s terms, but Kyiv still faces an unenviable choice