The Oscars used to be about art. Now they're about gratuitous luxury, and it's gross.

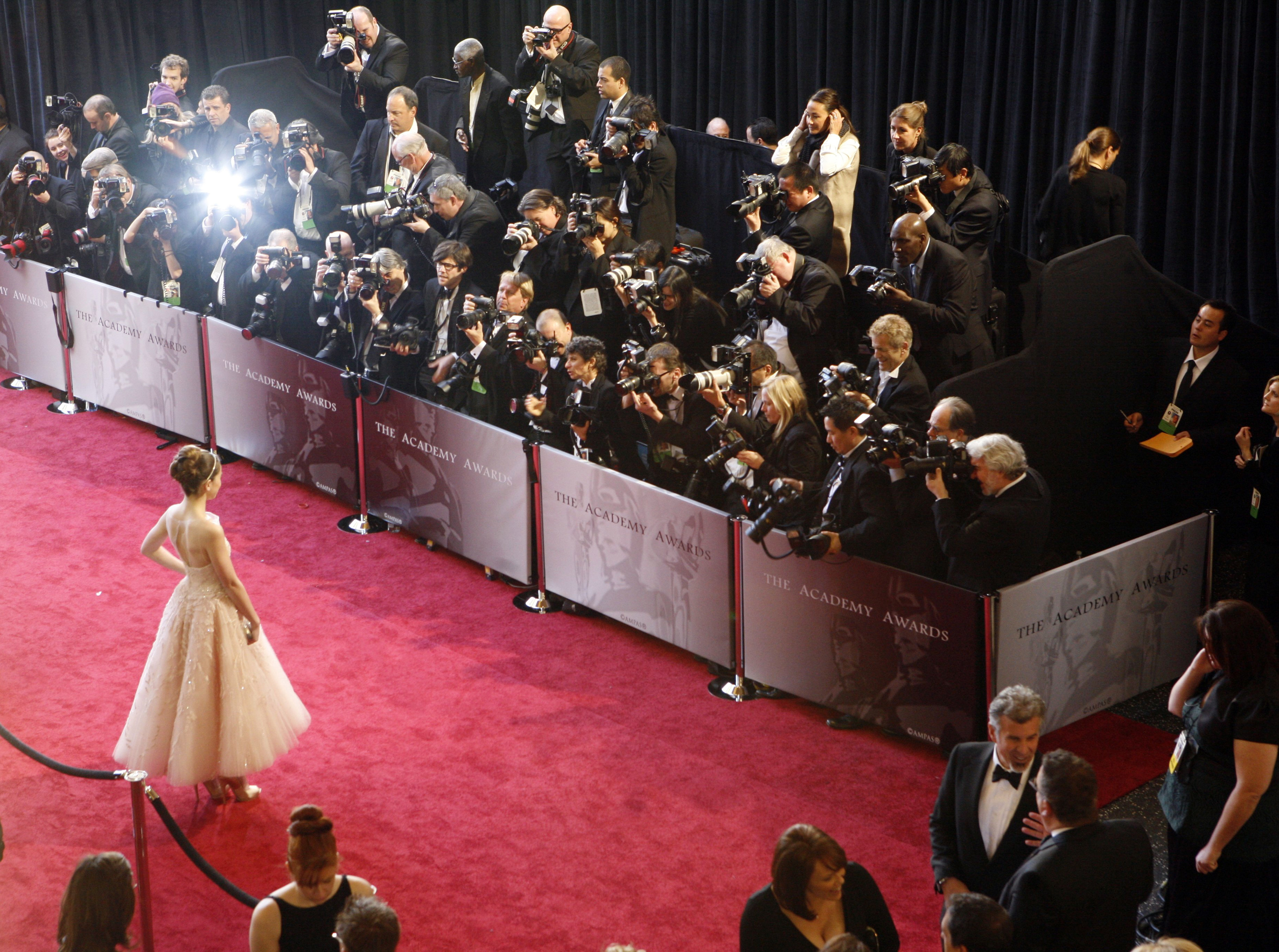

The red carpet has killed the Oscars

The 89th Academy Awards have arrived at a supercharged political moment — the kind Hollywood likes to return to in schmaltzy retrospectives about how the Oscars contributed to social progress. As with any legend, those stories tend to be double-edged: Hattie McDaniel may have been the first black Oscar winner (she won for playing Mammy in Gone With the Wind), but the real scandal was that the Ambassador Hotel, where the awards were held, was still segregated: She had to sit in the back of the room, away from the rest of the cast. Sidney Poitier was the first black man to win an Oscar for Best Actor in 1964, but the true controversy arose when Anne Bancroft gave him a congratulatory and scandalously interracial peck on the cheek.

When the Oscars have delivered genuinely challenging moments, they stand out because they don't align with brand or studio or corporate interests. These are the incidents that don't make everyone in the room feel good, like in 1973, when Marlon Brando protested the film industry's treatment of Native Americans by sending Sacheen Littlefeather, an Apache activist, to reject the award for Best Actor on his behalf. Or Vanessa Redgrave's speech in 1978 (accepting an award for Best Supporting Actress in Julia), in which she reiterated her and Jane Fonda's controversial support of a Palestinian state. Halle Berry and Chris Rock both addressed the Academy's inadequate recognition of black artistry — Berry in her acceptance speech in 2002, Rock as host in 2016.

The question facing this year's Academy Awards is this: How will it respond to the challenges of the moment? Will it follow in the tracks of the Golden Globes and the SAG Awards, both of which were unusually political this year? Or will it melt into the dull fashion contest to which it generally defaults?

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Despite the swag bags and million-dollar jewels and bank-breaking dresses, the Oscars — which seldom offer much of artistic or political substance — no longer offer even much in the way of fun. If it's a dystopia, it's a boring and ascetic one, devoid of even the venal pleasures of fashion and gossip and envy and vicarious good living. Under the harsh lights, the high-definition cameras, and the internet, Hollywood's messy decadence has hardened to a paranoid, perfect lacquer. The resultant spectacle — which is way too disciplined and polished to approach anything like pleasure — is a grim parade of human ascetics. Instead of competing for Best Picture, these actors are competing for best stylist.

To put it bluntly, the fashion police have won. The red carpet rules the Academy Awards. It's transformed an event that should be about artistic achievement in film (and secondarily, film's social importance, and thirdly, the envy and gossip the industry fosters) into a beauty industry dystopia that no one — save fashion critics — is enjoying.

We need to consider the consequences of these distortions and tally up what this beauty dystopia is costing us — in talent, in labor, in representation — while draining Hollywood's ability to respond to the challenge of the present.

Consider what actors who should be writing or rehearsing or producing or developing their craft are doing in the month leading up to the Oscars.

"Usually for red carpets, we take a month to prepare the skin," says a facialist who helps people prepare for the awards. "I use a mild electric current to drain puffiness, tone muscle, and tighten skin." Spray tans. Resurfacing peels. Oxygen treatments. LED therapy can make celebrities "look like they have spent the last month in a health spa."

But they haven't, have they? Instead, they've been avoiding salt and fasting via juice cleanses, all while exercising under the supervision of creepily focused instructors: "The goal is to burn more calories from the moment they wake up until they go to bed and I monitor it from my computer," says one such guru, who proudly limits his clients' net carbs to 40 grams. Are you thinking about your craft — or about writing or directing films of your own, or considering art's relation to injustice — when your profession strongly suggests that you starve and tighten and resurface and polish and shrink your skin if you wish to succeed?

No. You're descending into an industry-mandated dungeon of narcissistic torture in the name of looking inhumanly perfect for a few seconds on the red carpet — and perhaps you'll win Best Dressed, which might currently be the most powerful category of all. But actors are not models, and that they are expected to be is a problem.

Then there's the endlessly time-consuming and complicated problem of dress-choosing — stars will try on dozens of dresses while designers and stylists pair certain stars with certain brands based on each other's perceived value. The fittings take upwards of four hours. The styling team develops storyboards of looks for hair, makeup, shoes, accessories, etc. This is not a project, it's a production.

If this sounds fun for the star, think again: "No pre-parties for my patients! I urge them to stay home and try not to speak to anyone," says one industry prepper. "I gently remind them, 'You want to save your voice for when you really need it most.'"

In order to collect an honor for excellent acting, then, the actor — rather than act, or create, or eat, or engage with the world that enables her craft — must starve at home, brining in a salt and pepper bath (this is a thing), undergoing "colonic hydrotherapy," without speaking. Then there's the teeth whitening and liposculpture to dissolve the fat under their arms so they don't look droopy in sleeveless dresses. There's waxing and hair extensions and Juvederm and Botox (for face and armpits — stars must not sweat). Some will have their faces massaged from the inside to improve their appearance. And hey: If a little bit of flesh bulges under your shoulder blades where the strapless dress meets your skin, you'll need to liposuction that away.

Pause, for a moment, and consider what the red carpet used to be before there were stylists. Check out Bette Davis, who recycled an old costume for her red carpet look. Look at Ingrid Bergman's duck-footed joy. While many actors' dresses were made by terrific designers, Joanna Woodward made her own. So did Julie Christie.

But even those who are wearing designers and were therefore technically dressed by others — like Faye Dunaway in 1977 or Diane Keaton in 1978 — tell you something about themselves with their look. These people have not been polished into flawless surfaces by stylists. They are human and interesting. Look at Nicole Kidman in 1991. She looks fantastic even though her skin has texture, her eyebrows haven't been disciplined into brushstrokes, and she has pores.

The point is that fluency in fashion should not be a prerequisite for furthering one's career as an actor. But at this point, it basically is: Women who want to keep it simple by sticking to a look that works for them (like Jennifer Aniston or Angelina Jolie) are criticized for it. Women who don't care about the red carpet are admonished if they're young and relegated to kookdom if they're old.

One funny effect of all this is that luxury — the Hollywood excess which the Oscars in particular have celebrated — stopped seeming fun. There's a strained quality to it. At present, luxury means you can afford to zap off the extra skin that bulges off your dress. There's also a handy new tool called the "happy lift" that uses "micro threads" along the upper and lower outer lip to lift them into a smile so stars can avoid "loser face," the expression people involuntarily make when they don't get the award they want: "With a little thread or drop of Restylane, you can pretend — win or lose — that you don't care."

Luxury is being able to sew your mouth into a happy expression? This is horrifying.

Even the six-figure "swag bags" Oscars presenters and nominees receive are depressing. Yes, they include diamonds and a six-day trip to Hawaii and designer apples that won't brown — things none of these ultra-rich people need. But the best goodie bag in the world also includes underarm sweat patches and cellulite massagers. That's not the dreamy stuff of La La Land; it's a dull vision of stardom struggling to solve the problem of a smelly imperfect human body.

Sorry, but this version of luxury sucks. It makes art worse by hobbling half of Hollywood's artists with useless extra work. If women are expected to look not just beautiful but perfect while dressing in some intriguing but brilliant way, men are comparatively free: to think about other things, eat what they want, and put on clothes they feel comfortable in without melting off bits of themselves or micro-threading their lips into a smile. Their brands won't suffer if they wear the same old tux and forget to spend a month prepping their skin. They get a lot more time and — crucially — more mental space with which to create and produce.

It's a testament to women in Hollywood that they do create and produce and consider social questions while juggling these all-consuming extracurricular demands. But that doesn't make it fair or right or — in this political climate, with so much at stake — strategic. It's telling that Meryl Streep launched this year's trend of political speech at an awards show: Streep's rise in Hollywood came at a time when female artists were granted the right to live outside the HD tyranny of the red carpet and the fashion police. Oppressive beauty standards existed, of course, but actors could eat without endangering their careers and dress without dedicating a month to the project.

From a viewer's more selfish perspective, this all makes for a bad and predictable show. An Oscars where everyone looks perfect and smiles a perfect sewn-on smile as they hungrily wait for it all to end isn't what anyone wants. The greatest Oscars' moments meant something because people were present and responsive and engaged, both artistically as well as aesthetically. As the red carpet took over — and talk of designers and concern over personal "brands" took root — the strain of producing those perfect surfaces started to show. The Oscars should be about the art, the venal gossipy pleasures of competition, and the ethical questions that a group of artists can — if the will is there — address.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

Controversial GOP plan to sell millions of federal acres hits major roadblock

Controversial GOP plan to sell millions of federal acres hits major roadblockIN THE SPOTLIGHT Republican Sen. Mike Lee says he'll revisit legislation to sell millions of acres of federally held land to create 'freedom zones' of single family homes

-

One year after mass protests, why are Kenyans taking to the streets again?

One year after mass protests, why are Kenyans taking to the streets again?today's big question More than 60 protesters died during demonstrations in 2024

-

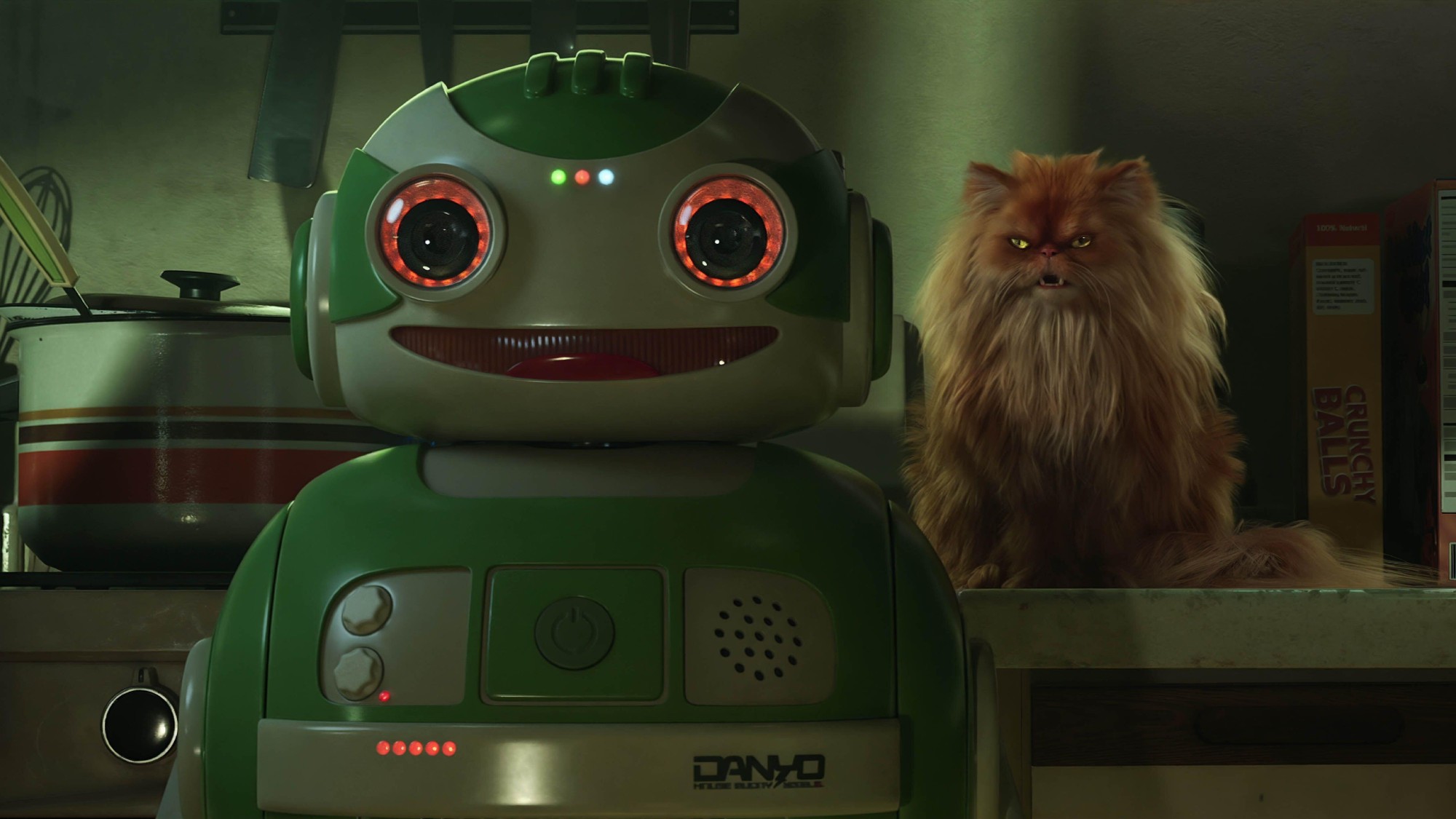

5 high-concept animated science fiction shows for grown-ups

5 high-concept animated science fiction shows for grown-upsThe Week Recommends How filmmakers are using a different medium to bring visionary science fiction to life