Are employers finally giving felons a second chance?

The labor market might be finally getting tight enough to help the most shunned group of all

One of the festering problems in the American economy is how our job market treats people with criminal records.

There are between 14 million and 15.8 million Americans of working age with felony convictions, and 6.1 million to 6.9 million of them are also former prisoners. Employers often rule them out as hires, putting them in a state of semi-permanent exile from all but the most poorly paid and exploitative fringes of the economy. A 2016 analysis by the Center on Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) estimated that the stigma against people with prison or felony histories prevents 1.7 million to 1.9 million people from working.

The consequences of this exile are both insidious and perverse. Getting a good job is one of the most important ingredients for reintegrating into society. But by cutting these Americans off from employment, we make it all the more likely they'll return to crime and then to prison. Their communities and families suffer when they can't find work. The life prospects of their children are set back.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One possible fix is to rein in America's completely out-of-control approach to sentencing and imprisonment. "It isn't just that we have the highest incarceration rate in the world," explained John Schmitt, a senior economist at CEPR who co-authored the analysis. "We have created a situation over the last 30 years where about one in eight men is an ex-offender."

But another fix would be to approach the problem from the opposite end and force employers to be more open to hiring to these Americans. The ongoing "ban the box" movement wants to do just that, by preventing employers from asking about criminal records on initial hiring forms. That way, businesses have to at least give applicants a face-to-face interview before learning of their criminal history and writing them off.

Yet there's an even more fundamental fix to this problem and it's one the U.S. is slowly creeping up on almost by accident: Get the unemployment rate low, and keep it there.

At bottom, employers don't hire people with criminal records because they can afford to be picky. So long as the number of people looking for work vastly exceeds the number of jobs being created, businesses can write off potential hires for all sorts of reasons without having to worry about losing potential sales, competitiveness, or market share. Between several major recessions, culminating in the 2008 collapse — plus an overall shift to slow and anemic recoveries — employers have spent the last few decades regularly enjoying this luxury.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But occasionally, the unemployment rate gets low enough to flip the script. Employers then can no longer afford to indulge their biases without it hitting them where it hurts — in the pocketbook. We briefly saw that happen in the boom economy of the late 1990s, when the unemployment rate ultimately got down to 4 percent.

The recovery from the Great Recession has been agonizingly slow. But unemployment is now at 4.4 percent and shows every sign of continuing to fall. The stigma against criminal records is particularly prevalent amongst Americans without high school educations, and unemployment for that socioeconomic group fell 2 percentage points since September — while the unemployment rate for people with college educations held steady.

There's finally anecdotal evidence that employers are once again feeling the pinch.

"While the government doesn't track jobs for those with arrest records, people are increasingly getting hired, according to economists, companies, and government officials," Bloomberg recently reported. The home construction sector in several states is beginning to make concerted efforts to hire people just coming out of prison who have taken classes in things like carpentry and plumbing. The Council of State Governments Justice Center is giving logistical help for hiring ex-offenders to the 1,300 business groups that make up the Association of Chamber of Commerce Executives.

So have things turned a corner for those with criminal records? It's too early to tell.

As CEPR has also shown, there's still plenty of evidence the job market is considerably weaker than it was in the late 1990s. Labor force participation is still depressed and the employment rate for prime-age workers is still lower than the mid-2000s peak — which was in turn lower than the late 1990s peak. Wage growth is probably the most telling indicator of how much pressure businesses feel to attract new hires, and it remains unusually low as well. Employers are still pulling in new hires from the ranks of the young and the long-term unemployed while feeling free to offer them basement-low wages.

Gerald Howard, chief executive officer of the National Association of Home Builders, may have told Bloomberg his industry faces a "huge labor shortage." But what counts as "huge" is in the eye of the beholder. The unemployment rate needs to keep falling and the pressure on employers needs to keep heating up before everyone gets the second chance that society owes them.

There are a few practical lessons from this. At a minimum, lawmakers should avoid doing anything stupid that could damage the economy — like massively cutting welfare state spending and public investment. Preferably, they'd be doing new rounds of Keynesian fiscal stimulus to boost aggregate demand, create even more jobs, and bring the unemployment rate down faster. Far from worrying about inflation, the Federal Reserve ought to tolerate an inflation rate that stays well above its 2 percent target for quite a while.

But as a society, we should remember that when you live with a sick economy long enough you can lose sight of what a healthy one looks like. And we should remember the Americans left behind when that happens.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

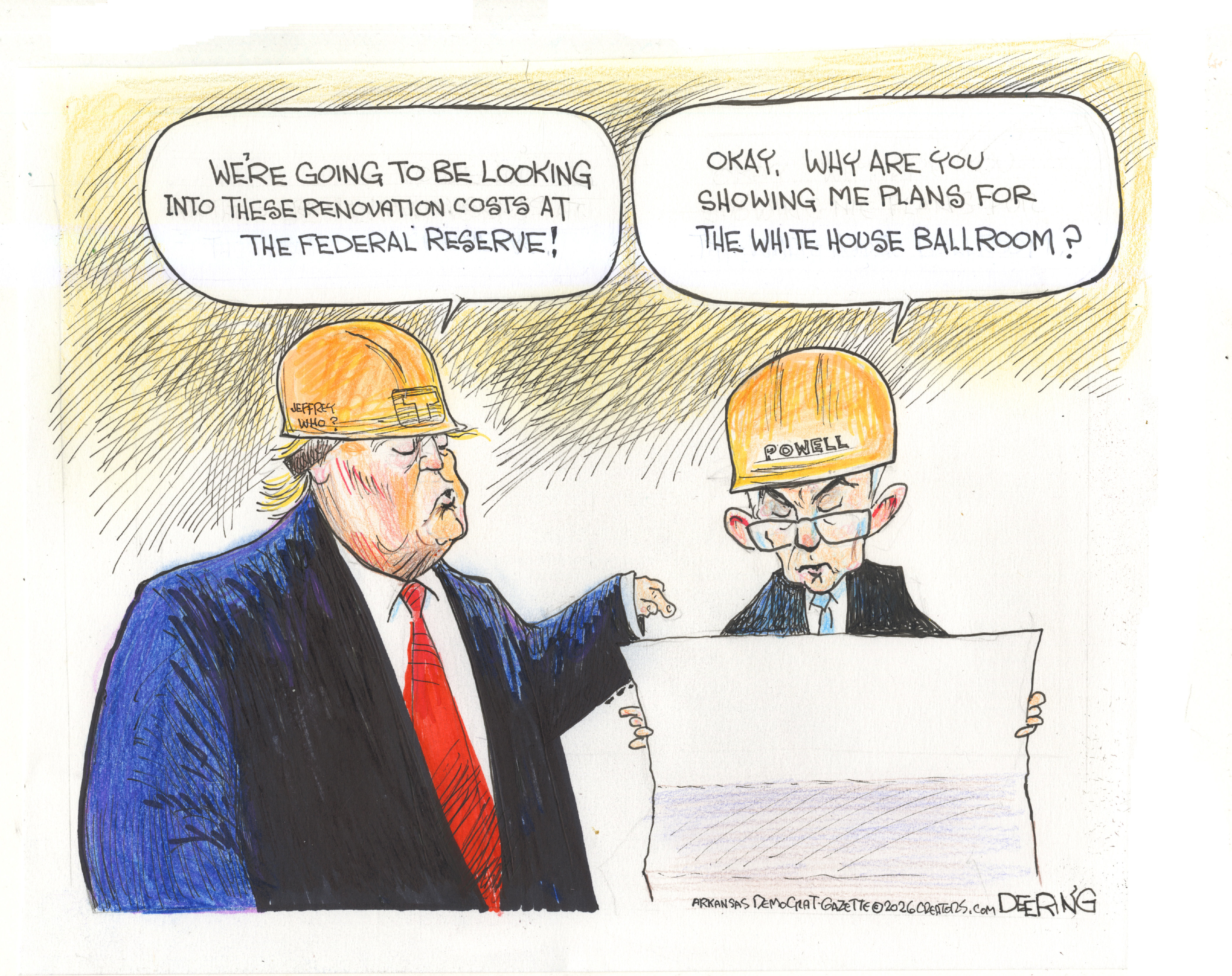

Political cartoons for January 17

Political cartoons for January 17Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include hard hats, compliance, and more

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy