Amazon eats the world

The company is taking over everything. Here's how.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you've ever seen the Pixar movie Wall-E, you might remember Buy-N-Large, the satirical megacorporation that provided for every conceivable aspect of human existence. That's basically Amazon's business strategy now.

The online retailer is taking at least one big step, and maybe two, towards becoming its cinematic doppleganger. Specifically, Amazon announced last week that it will buy the high-end grocery chain Whole Foods in 2017. And reports surfaced it might purchase the office messaging platform Slack as well.

Let's take these in turn.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Amazon's whopper purchase of Whole Foods for $13.7 billion is far and away the company's biggest acquisition yet. It's also part of a much larger battle: Amazon dominates huge swaths of online retail, with a market value larger than the next 12 biggest traditional retailers combined. But one area where it still lags is groceries. The company is experimenting with a grocery delivery service for Amazon Prime members, and another service that lets grocery shoppers skip the checkout line. But buying Whole Foods would instantaneously and massively expand Amazon's capacities in the grocery business — and bring us that much closer to a world where the groceries come to us, rather than vice versa.

Amazon will also get access to Whole Foods' 430 locations. The grocery chain will keep its brand, its CEO John Mackey, and its Austin, Texas, headquarters. But its profits and operations will be under the umbrella of its new parent.

That will give Amazon a leg-up in its larger war with Walmart over who will become the dominant force in both brick-and-mortar and online retail. Walmart is trying to expand its web offerings, thus moving into Amazon's turf. So Amazon is trying to expand its physical infrastructure — both to get a stronger grip on the physical retail business, but also to improve its online delivery service. "Amazon clearly wants to be in grocery, clearly believes a physical presence gives them an advantage," Michael Pachter, an analyst at Wedbush Securities Inc, told Bloomberg. "I assume the physical presence gives them the ability to distribute other products more locally. So theoretically you could get five-minute delivery."

Then there's Amazon's possible purchase of Slack — a deal that could value the office messaging application at $9 billion. This would be a strategic gambit in yet another war, over who will dominate the world of online business tools.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Offices across the economy are increasingly turning to cloud computing and suites of online tools offered by a handful of big tech companies. Amazon is already a big player in this space and offers both services. But the one thing Amazon lacks — and that Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Facebook all already have — is a messaging platform.

Slack, meanwhile, has been quite successful: It boasts five million users, including one million paying users, and, as of 2016, was already valued at $3.8 billion. It's also pursuing another $500 million in fundraising that would up its valuation to $5 billion. So Slack would plug right into Amazon's suite of business offerings, providing a messaging and conferencing platform to tie its cloud computing and office tools together. On top of that, Amazon wants to expand further into the market of business-to-business transactions. Slack gives it a readymade path, plus an excellent platform for ads.

Also worth mentioning is Alexa, Amazon's voice-activated AI personal assistant, which comes on its Echo speakers. Amazon has sold 11 million units as of January.

Echo and Alexa can already be found in homes and hotel rooms, and they're coming to cars next. So workplaces are the last missing link, if this sort of conversational interface is going to be the next big thing. Slack could tie all that together, too.

So there it is: Amazon has already conquered most of your online retail shopping. It's in your home and will soon be in your car. Next it's coming for your office and your groceries. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos already owns The Washington Post. Should his company ever get into real estate, Amazon could literally become the real-life Buy-N-Large, and we could all live our entire lives under its corporate auspices.

That probably sounds like a dystopian scenario. And Pixar certainly intended it that way when they lampooned such a future in Wall-E. But even if you're not moved by the romance of small businesses and local civil society, there's something else to consider.

What Amazon is engaged in is a classic example of vertical integration — when a company owns both the market infrastructure by which goods and services are distributed (say, online retail) and the goods and services themselves (say, groceries). A few decades ago, antitrust law forbade vertical integration outright. If you own the infrastructure and compete with other businesses that sell on that infrastructure, you can lock out and undercut your competitors. Vertical integration allows for monopoly power. Furthermore, old-school antitrust enforcement would never have allowed Amazon to gain the market share it enjoys.

But antitrust law changed drastically in the 1980s, which helped open the door for Amazon to go down this path.

The problem with monopoly power is it undercuts competition: It allows a company to extract more and more wealth from its customers — and from businesses throughout the economy — all while doing less and less to actually add value. Monopoly power is an engine driving inequality and wage stagnation, job destruction and dying towns. It will be a boon for Bezos and his fellow shareholders, and a boondoggle for the rest of us.

But hey, at least Buy-N-Large — I mean, Amazon — will be there to offer you a great deal on parsley.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

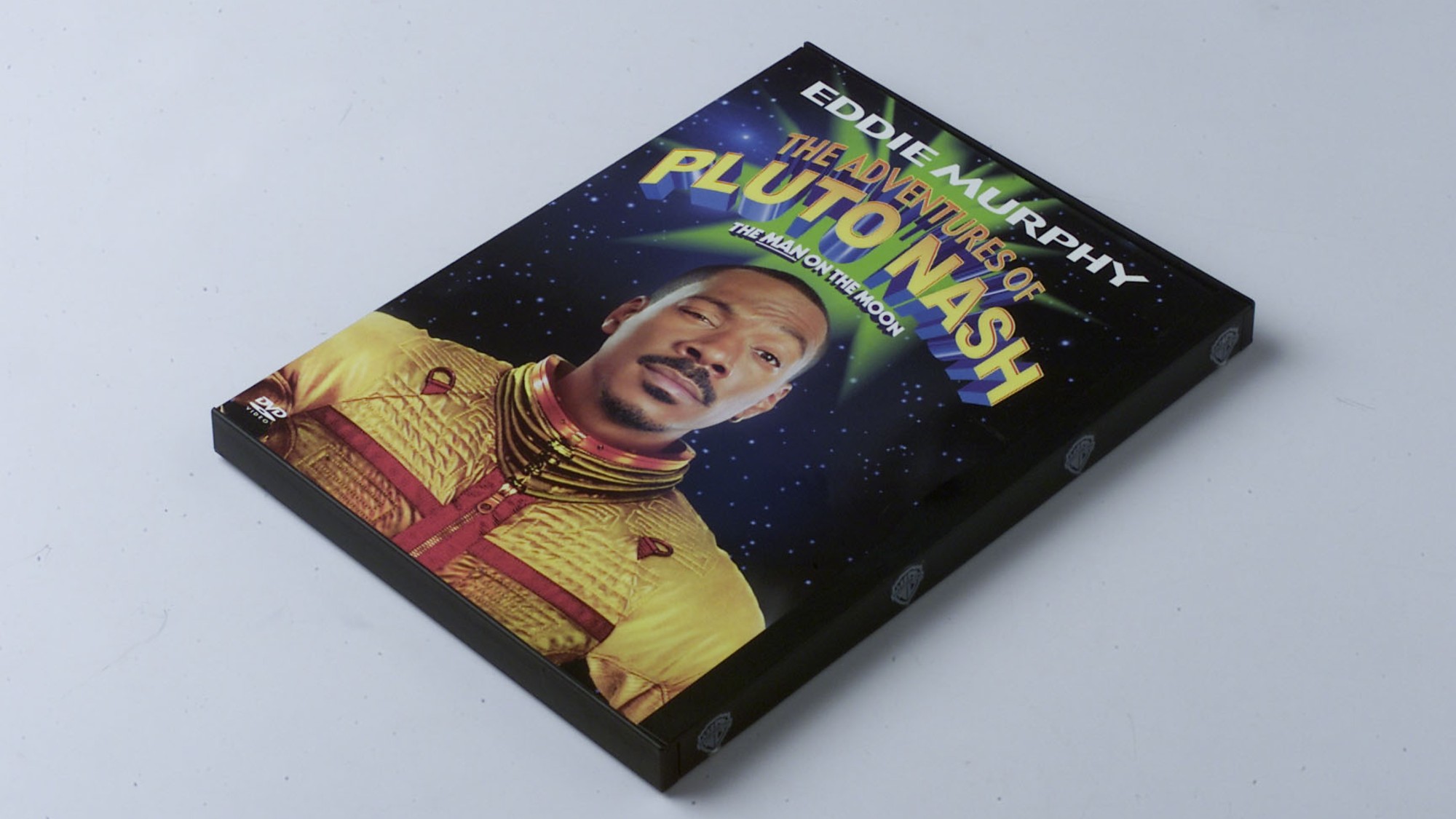

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy