The great video game scare of 2017

America's economy is messed up. It's not because of video games.

America faces a massive array of daunting economic challenges. But Overwatch, Final Fantasy, and Call of Duty are not among them.

You may have heard otherwise, thanks to the media deluge about a new study titled "Leisure Luxuries and the Labor Supply of Young Men," which suggested that really awesome video games explain why young men don't work more. Researchers noted that between 2000 and 2015, hours worked by men ages 21-30 fell by 12 percent, compared to an 8 percent decline for men 31-55. And as young men's leisure time increased, time-use studies show, most of those additional hours were spent playing video games. This wasn't the case for older men. Or as the study put it, "Improved leisure technology played a role in reducing younger men's labor supply."

Video games might well be a factor in young men deciding whether or how much to work. But concerned parents should slow their roll before they start unplugging and hiding all those Playstations and Xboxes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

First of all, it's a red flag that the big gaps in hours and employment between younger and older men emerged during the Great Recession and Not So Great Recovery. There are lots of potential non-video-game explanations for this. For instance, employers might have started demanding more education or experience before hiring during a time of economic tumult.

As my American Enterprise Institute colleague Stan Veuger explains, "Think of a world where suddenly no one ever gets hired, only fired, for example. All young people would be unemployed but previously employed old people keep their jobs. That's not crazily different from a world where job openings went from 4.5 million to 2 million — though of course there were mass layoffs as well."

The big jobs event in 2007 wasn't the release of Halo 3. It was the start of a severe economic downturn.

If the recession and recovery played a big role in young men working less, then work rates should improve the further we move into the economic expansion. And that's exactly what seems to be happening. The employment-to-population ratio — the share of a particular population with a job — for 20- to 24-year-olds fell to 61.3 percent in 2010 from 72.7 percent in 2006, the last full non-recession year.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But that number has since rebounded to 66.2 percent. Is video game quality suddenly getting worse? Of course not. It's just that an improving labor market seems to be drawing young men back in. Indeed, as the study notes, non-employed young men actually reduced their total leisure time by five hours a week between 2012 and 2015, versus the 2004-2007 period, as they scrambled to find a job. That, even though total time spent gaming increased.

It's also unclear what role video games play in long-term employment trends for young men. From 2000-2016, their employment-to-population ratio fell by about 10 percentage points here in America. But in Japan, another country where video game playing is presumably a common leisure activity, the work ratio has actually increased a bit over that same span.

In a way, the video game scare is the flipside of concerns that robots are taking all of our jobs. In one case, technology is supposedly hurting the demand for work, in the other, the supply of work. But the big problem with the U.S. economy over the past decade isn't automation or trade, it's the fact that we suffered a massive financial shock and near-depression. It takes awhile for economies to recover from those.

What is an actual problem is the long-term decline in labor force participation for men from their mid-20s to mid-50s. And as Moody's economist Adam Ozimek notes, "Solutions to the problem of joblessness should not start with radical ideas such as guaranteed jobs programs, but old-fashioned ways for improving labor markets."

He suggests expanding the the Earned Income Tax Credit to younger workers and making it more rewarding for currently eligible workers without kids. Other ideas include criminal justice reform and lowering occupational licensing requirements, as outlined by the Obama White House in 2016.

Gamers can still be workers — although their parents may need some convincing.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

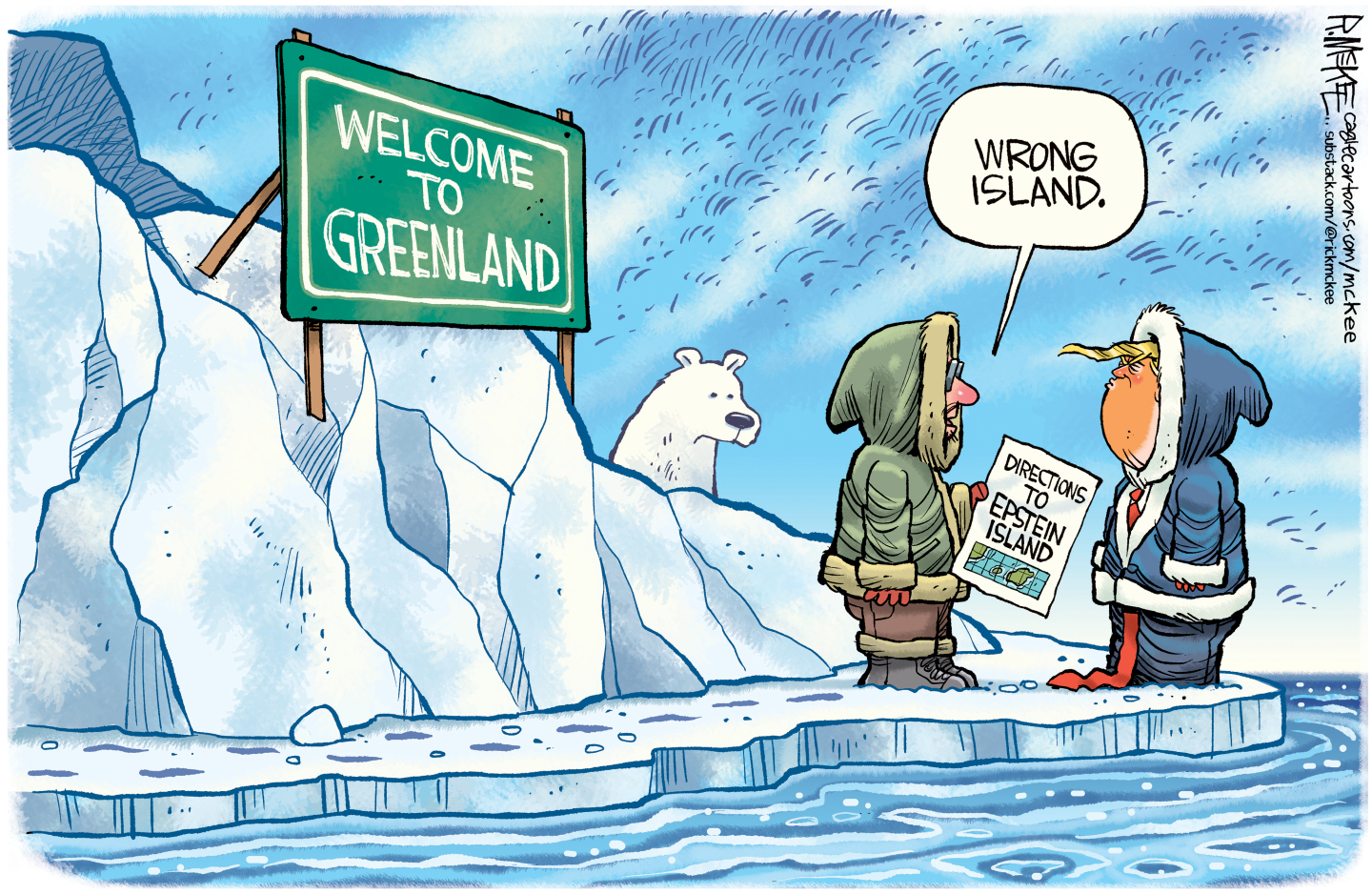

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade Greenland

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade GreenlandCartoons Artists take on misdirection, the need for Greenland, and more