Gauri Lankesh was a brilliant and brave journalist. She was my friend. And they murdered her.

Did Gauri pay with her life for fiercely opposing militant Hindu nationalism?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The rising forces of religious extremism, intolerance, and lawlessness in India inflicted a terrible casualty this week: They slayed my dear friend, Gauri Lankesh, the nation's bravest and fiercest journalist.

If a country's moral health is to be judged by its capacity to handle dissenters and critics, then my birth land — and the world's most populous democracy — is in a truly dark place.

Gauri was gunned down by unknown assailants outside her home in Bangalore, India's equivalent of Silicon Valley, as she stepped out of her car. Reports suggest that her assassins were lurking outside her driveway awaiting her return from work. They sprayed her small frame in a hail of bullets and sped away.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Unfortunately, she is not the first Indian journalist to be murdered so gruesomely — or brazenly. It is not clear who was behind the attack, but at least three of her "spiritual" brothers who, like her, spoke out against the alarming growth of Hindu militancy and shrinking secularism have been likewise struck near their homes in the last few years. None of the murders have been solved, something that distressed Gauri to no end — not because she was overly concerned about her own safety (she always told me not to worry, "love and hugs!"), but the chilling effect such violence has on speech.

In 2015, India was among the three most dangerous countries for journalists, worse than Pakistan and even Afghanistan. Death threats against a long list of journalists whom Hindu militants daily berate as "libturds" and "presstitutes" have become commonplace. Such coarse and violent language has dehumanized journalists in India, making violence against them seem justified. Yet Prime Minister Narenda Modi, a Hindu nationalist himself, has not seen fit to make a national appeal against such hateful invective. More tellingly, he has yet to issue a statement condemning Gauri's assassination, despite demonstrations and candlelight vigils by heartbroken scribes and grieving fans all over the country. She also got an official funeral by the state government, which would have surely made her laugh given that the same government, just a few months ago, convicted her for criminal defamation for exposing two Hindu politicos who had swindled their own party's workers. She was sentenced to six months in prison (postponed pending an appeal) — a clear effort to punish her for her opinions, she noted.

To say that Gauri, whom I met in journalism school in New Delhi 34 years ago, was a remarkable woman would be an understatement. She combined a gentle warmth, profound compassion, and easy forgiveness with a steely, unwavering, moral conviction. She was also preternaturally humble and honest — a hero because she never dreamed of being one.

We bonded over boy talk and politics — in that order — during all-night gossip sessions as she filled up the ashtray and gave me a contact high. She was already well on her way to sorting out her politics even before we met when, barely out of high school, she bylined a piece, "Objection Overruled," lambasting a Supreme Court ruling that banned women from appearing in court in jeans, slapping a picture of her riding a scooter in a denim jumpsuit on it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Still, she listened more than she opined, which was one reason that neither one of us dreamed then that two decades later she would single-handedly found the eponymous Gauri Lankesh Patrike — a tabloid that combines the counter-establishment politics of the Village Voice with the gossipy salaciousness of the New York Post. And what's more, turn it into such a fierce and uncompromising voice against India's triple bane of "communalism" (religious fanaticism), "casteism" (caste oppression), and corruption that it would get her killed.

She shared these causes with her father, himself a highly successful tabloid publisher whose newspaper she ran for 10 years after his death before quitting following a spat with her brother. She used to say that her progressive father, whom she revered, turned her into a feminist.

She wanted to promote her father's legacy, no doubt — which is why, despite her faltering grasp of Kanada, the local language, she opted to publish her newspaper in it, as he had done. He had convinced her that if she wanted to fight for the underdogs — poor farmers, dalits (untouchables), low-wage women — she had to reach out to them in their language — not that of English-speaking urban sophisticates. She also embraced his business model, refusing advertisements lest they dilute her paper's anti-establishment commitment, and depended solely on subscriptions — which had to be kept nominal if her target audience were to afford them.

But she was more than her father's daughter. Gauri had to fight fights that her dad didn't.

She was a cosmopolite at heart who loved Bangalore because of its openness and tolerance. It was one of safest cities in India for women in the 1970s and 1980s when women could, as she wrote, hop on their "RX 100 Yamaha motorcycle" and go "whrooming, without raising an eyebrow." Women inhabited the pub scene as much as men — and not in long skirts with loose blouses, Gauri observed, but "jeans and a Little Black Dress." Bangalore didn't have a "live and let live" ethos, it had an "adjust a little" attitude — meaning that every religion and way of life happily made space for the others.

All of that began to change over the last 15 years with the increasing "saffronization" — saffron being the color worn by Hindu fanatics — of her state. Hindu thugs in both parties — BJP, the majoritarian Hindu party, but also Congress, the so-called secular party of religious and other minorities — started thrashing women who wore "immodest" clothes or celebrated Valentine's Day. They invented the threat of "love jihad" — Muslim men seducing Hindu women — to justify terrorizing Muslims in the state. She understood before many others that the project of this new, virulent form of Hinduism was to resist reform of its own regressive practices while demonizing India's minority religions for theirs.

Gauri was going to have none of that. She mounted scathing attacks on them. She used strong — though, unlike her enemies, never abusive — language, named names, and connected dots. But what made her truly dangerous was that she yielded not an inch in her patriotism. She was an atheist and something of an Enlightenment rationalist who demanded a radical separation of religion and state. But she defended her views not by referring to Western thought but India's own rich intellectual traditions, making their standard accusations against their political opponents as "anti-national" or "anti-Hindu" fall flat when hurled at her. The authentically indigenous mode of her writings fundamentally deflated their claims of being the "true" representatives of their country and culture.

She knew Hindu mythology in all its resplendent local diversity long before University of Chicago's Wendy Donniger wrote a scholarly treatise about it. So she could counter Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) efforts to impose its dogma by referring to Hindu epics and scriptures and showing just how contrary to the true spirit of Hindu pluralism their ideas were. The source of her own lack of faith in god, she once told me, was Charvaka, an ancient materialist school of thought within Hinduism. She mercilessly mocked public figures whose misguided displays of piety, consciously or unconsciously, entrenched upper-caste Hindu hegemony. (For example, she wrote a piece last year lambasting India's president in 1951 who publicly washed the feet of 201 Brahmins and drank the water as "vulgar" — a virtually blasphemous thought in today's India.)

She made mistakes and had her blind spots, to be sure. Unlike me, she had a strong socialist streak. She didn't condemn Naxalism — a militant Maoist movement in India that fights for lower castes and farmers against feudal, upper-caste landlords — as forcefully as she should have. She called for the "rehabilitation" of its members because she saw them as more misguided than dangerous — and also because, whatever their excesses, they paled in comparison with those of a violent state that without any due process killed real and alleged Naxals in fake "encounters" (confrontations), including one with our journalism school friend, Saket Rajan, whose death profoundly affected Gauri.

The Charlie Hebdo attacks perpetrated by Islamist terrorists in France generated worldwide condemnations. But the climate of hate created by Hindu fanatics against Indian journalists has elicited barely a peep. This is partly because Hindu extremism is still a local phenomenon whose poison hasn't yet spread. And it is partly because the West, thanks to its own insularity, still sees India as the land of white doves and Gandhi. It simply hasn't adjusted to India's new reality.

Gauri's assassination shows just how far India's once-proud liberal democracy has fallen. It will be up to us, her liberal comrades and friends, wherever we are, to try and lift it up again.

May we make your country worthy of your sacrifice one day, Gauri. Love and hugs.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.

-

Companies are increasingly AI washing

Companies are increasingly AI washingThe explainer Imaginary technology is taking jobs

-

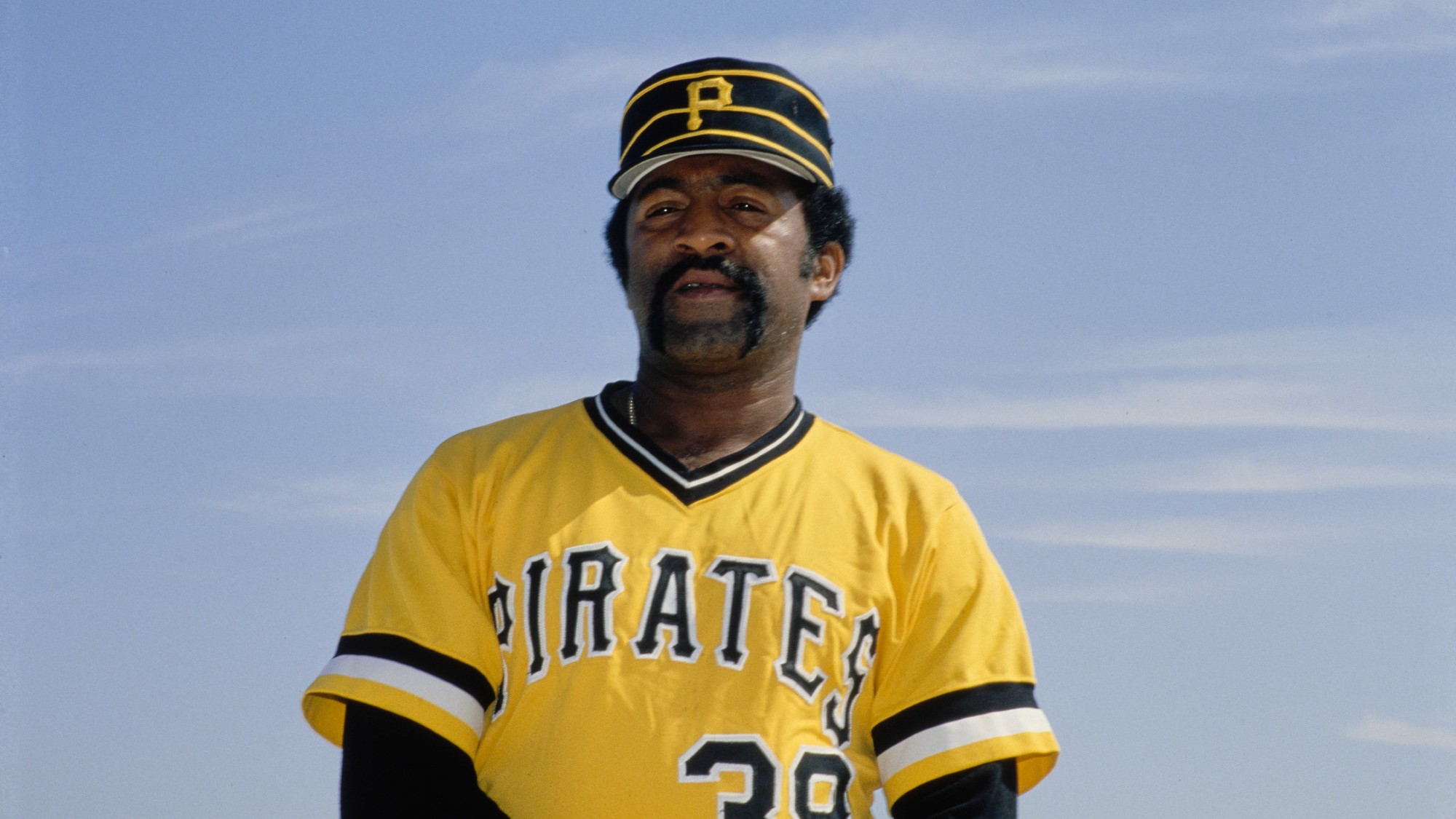

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Fame

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Famein depth These athletes’ exploits were both real and spectacular

-

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military