The GOP's child tax credit is an insult to American families

It would give a family making $1 million 44 times more cash than a single mother earning minimum wage

A new and improved child tax credit was supposed to be the saving grace of the Republican tax reform plan.

One way or another, Republicans were always going to massively cut taxes for corporations and the wealthy. But a persistent group of reform conservatives — spearheaded by Sens. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) — has been pushing to expand and upgrade the child tax credit (CTC) as well. Properly upgraded, the CTC could do enormous good reducing child poverty and helping working families with the spiraling costs of child care. However hare-brained the Republicans' ideas for boosting jobs and wages may be, the CTC seemed one place where the party had talked itself into doing something great.

With the House and Senate tax plans now before us, it's clear things didn't work out that way.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

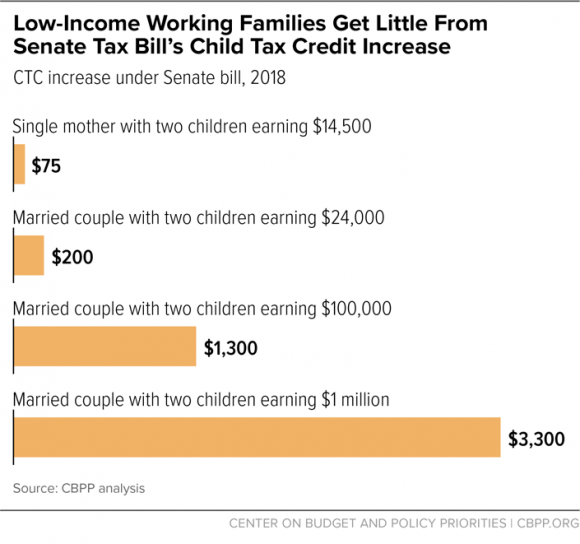

Let's start with the Senate version. In fairness to the bill, the CTC is horribly designed to begin with. The Senate bill wouldn't make anyone worse off, and it would modestly expand benefits for some low-income families. But when I say modestly, I mean modestly. "Whereas a single mother with two children who works full time at the minimum wage and earns just $14,500 would receive a child credit increase of only $75, a family of four with a $1 million income would get $3,300," wrote Chuck Marr, the director of federal tax policy at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. In other words, a family making $1 million would get 44 times more money from the government than a single mother earning the minimum wage.

To understand the reason for this grotesque discrepancy, you have to understand the credit's design.

As it stands, the child tax credit maxes out at $1,000 per child. It also begins to phase out for individual earners with kids who make at least $75,000 — and for married earners with kids making at least $110,000 — and falls to nothing for richer families soon after.

But the CTC also has two really pernicious aspects.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

First, a family has to earn at least $3,000 before they even qualify for the credit.

Second, refundability is a crucial aspect of any tax credit's ability to help the less fortunate. Let's say you qualify for the CTC, but your family only owes $500 in taxes to the federal government. If the CTC were fully refundable, you'd get the remaining $500 back as a check. Unfortunately, the CTC is only partially refundable: the check back is limited to 15 percent of your earnings over the initial $3,000 threshold. So if your family made $5,000, the refundable portion of the CTC would only be $300. (That's 15 percent of the $2,000 leftover when you subtract $3,000 from $5,000.)

The result of these two limitations? Millions of the poorest families get no help at all from the CTC, and a family has to earn about $10,000 before they see the full $1,000-per-child refund. Since low-income parents need the help the most, this is deeply perverse.

The Republicans' Senate bill would increase the CTC to $1,650 per child, which seems like a good thing. The problem is, they don't change that weird 15-percent limit on refundability, and they only drop the qualifying income threshold from $3,000 to $2,500. As a result, 10 million children in working families would see a paltry $75 increase. (That's 15 percent of the extra $500 freed up by dropping the threshold.)

On top of that, the Senate bill also caps the portion off the CTC that can be refunded at $1,100 per child rather than the full $1,650. As a result, that means another 14 million kids in less fortunate households wouldn't get the full $650 increase.

Finally, the Senate GOP massively expands the upper income limit on who can qualify for the CTC — it doesn't begin phasing out until $1 million for a couple. There's nothing inherently wrong with that, as plenty of families making six figures still struggle with expenses like child care and education.

But when combined with the distributional effect for families lower down the income ladder, the final effect is pretty stunning.

The reforms to the child tax credit put forward by House Republicans are a bit different, but they result in the same mishmash. The credit would phase out for married couple earning over $230,000, which is an improvement over the Senate bill. But the House bill would also only increase the credit to $1,600 per child, it would cap the portion of the CTC that could be refunded, and it wouldn't lower the $3,000 threshold for qualifying income at all.

This isn't an accident or an oversight. Dig through right-wing thinking on how to reform the CTC, and you quickly realize that conservatives' biggest concern is not child poverty per se. Instead, they are more concerned with low American birth rates, which they see as driven by the welfare state, and with their suspicion that government assistance creates bad incentives — especially for the poor. Those overarching concerns create an inevitable preference for a child tax credit that concentrates its help on upper-class parents rather than lower-class ones.

Rubio and Lee's own proposal has been around for several years, championed by conservatives who want the GOP to show more concern with working families. It would increase the CTC to at least $2,000 per child (ideally $2,500) and make the CTC refundable against the payroll tax as well as the income tax. Since low-income and working-class families' payroll tax liability is usually larger than their income tax liability, this would greatly expand the CTC's ability to help the less fortunate. So both the Senate and House CTC proposals are badly watered-down versions of Rubio and Lee's plan.

Their approach doesn't entirely escape the perverse logic of conservative ideology. But it's definitely better than the GOP's current offerings. And to their credit, the two senators are willing to make noise about it: "While we are glad to see an increase to the child tax credit, like the House bill, it is simply not enough for working families," Rubio and Lee said in a joint statement.

Meanwhile, during the 2016 campaign, Hillary Clinton wanted to boost the CTC to $2,000 for families with children under 4 years old. She also wanted to eliminate the $3,000 qualifying threshold entirely, and change the 15-percent limit on refundability to 45 percent.

But all of these proposals have been put to shame by the plan Sens. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) released in October. They would boost the the CTC to $3,600 for children up to age 5, and $3,000 for children age 6 to 18. They would eliminate the $3,000 qualifying threshold entirely, and completely scrap the limits on refundability. Basically, all families would see the full $3,600 or $3,000 per child on their very first dollar of income.

The only thing that would be better is taking the benefit out of the tax code entirely, and transforming it into no-strings-attached cash aid to every family with children — a true universal child allowance.

Bennet and Brown have now set the bar for the Democrats. Unfortunately, it's the Republicans who are in power. And they're still falling far short.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Is Europe finally taking the war to Russia?

Is Europe finally taking the war to Russia?Today's Big Question As Moscow’s drone buzzes and cyberattacks increase, European leaders are taking a more openly aggressive stance

-

How coupling up became cringe

How coupling up became cringeTalking Point For some younger women, going out with a man – or worse, marrying one – is distinctly uncool

-

The rapid-fire brilliance of Tom Stoppard

The rapid-fire brilliance of Tom StoppardIn the Spotlight The 88-year-old was a playwright of dazzling wit and complex ideas