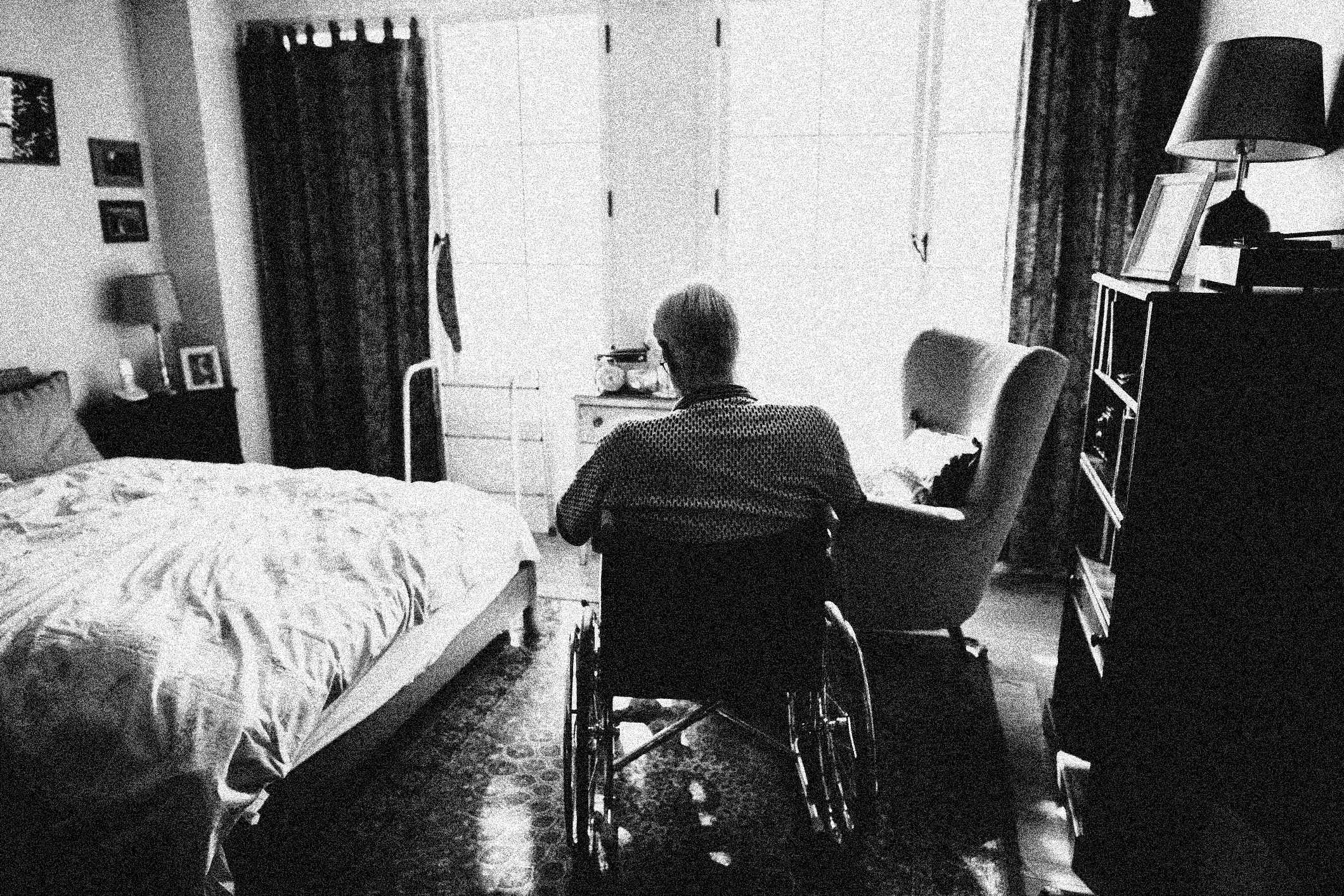

Why retirement is breaking the elderly

Retirement used to be a collective problem. Now it's yours.

The American economy may be booming. But not everyone is participating in the bonanza. And one of the groups increasingly left out of the party is America's retirees.

The latest evidence comes from the Consumer Bankruptcy Project, which found that the rate of bankruptcies among the elderly has tripled in the last 25 years. In 1991, there were only 1.2 bankruptcy filers per every 1,000 people over 65; by 2006, there were 3.6. Over 12 percent of all bankruptcy filers are now Americans 65 and older, up from 2.1 percent over the same time period. And the next generation is on track to continue this ominous trend.

Now, the absolute number of Americans over 65 filing for bankruptcy remains relatively small — roughly 100,000 per year. But "the people who show up in bankruptcy are always the tip of the iceberg," University of Illinois law professor Robert Lawless, one of the researchers, pointed out to The New York Times.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In other words, these numbers hint at a far vaster expansion of financial insecurity among the elderly.

To explain how this happened, the researchers reference the idea of "risk shift" put forward by political scientist Jacob Hacker. This is when the burden of paying for a risk is moved off the shoulders of some collective entity — like companies or the government — and onto the shoulders of isolated individuals instead.

How does this apply to retirement?

Well, no longer working involves risk. You're relying on various investments, government programs, and insurance to cover all your needs, even as you no longer get a regular paycheck from a job. The researchers pointed to several big changes that have offloaded these risks onto individual retirees: "Longer waits for full Social Security benefits, the replacement of employer-provided pensions with 401(k) savings plans, and more out-of-pocket spending on health care," as the Times summarized. "Declining incomes, whether in retirement or leading up to it, compound the challenge."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Let's break that down.

Social Security is the single biggest source of income for retirees. It's an example of U.S. society as a whole, via the federal government, taking on some of the risks of funding people's retirement. But the retirement age to start receiving Social Security benefits has been increasing: It used to be age 65, it was gradually increased to 66 by 2017, and is now on its way to 67.

This is a de facto cut in benefits. The earliest age you can retire remains 62. But if you take your Social Security benefits then, you're penalized with a lower income. For people who can't fully retire until age 66 or 67, versus 65, the penalty of taking retirement early is even worse. The result? People heading into retirement these days are forced to make other resources stretch further.

Then there's out-of-pocket spending on health care.

Medicare doesn't cover all the health expenses for American retirees. They usually need supplemental insurance from the private market. But the costs of drugs and treatments and procedures have been rising for decades. That makes it harder for insurers to offer the same level of coverage while still making the same profits. They've solved that problem by simply covering less and less, while using policies like larger deductibles and more co-pays to foist more of the costs onto individual Americans. Most retirees spend around 20 percent of their income on out-of-pocket heath care.

Again, we have a risk shift from a collective entity — the insurance company, covering the costs of care with resources pooled from thousands or more paying customers — onto individuals and families.

But perhaps the most potent example of this shift is the disappearance of the defined-benefit pension. This was basically Social Security at the company level: In return for years of labor, a business would pay a worker a fixed income upon their retirement.

In the midcentury, such pensions were common. But they also increased operating costs and lessened the amount of money that could be spit out as profits to shareholders. So American businesses gradually reduced defined-benefit plans, and today they're almost extinct.

What's taken their nominal place is the 401(k). But while businesses do sometimes help with putting money into 401(k)s, the amount of resources in the investment portfolio is ultimately a function of what each worker can sock away on their own. And unlike a defined-benefit pension, the income a 401(k) can provide is at the mercy of the stock market as well as the predatory fees of Wall Street. Predictably, 401(k)s have proven a grossly inadequate substitute for the pensions they replaced.

Debt overhangs have gotten worse for retirees as well. From 2001 to 2013, the portion of households headed by someone over 60 that also had some amount of debt went from 50.2 percent to 61.3 percent. And as bad as things have been for younger workers, especially after 2008, more retirees have had to guarantee or cosign their children's debts as well. "I never saw parents with student loans 20 or 30 years ago," a Seattle bankruptcy lawyer told the Times.

Compounding all of this are the decades of wage stagnation most Americans have experienced. That means workers have less money to put into their 401(k)s, fewer resources with which to supplement lower Social Security benefits, and ultimately less income to spend on out-of-pocket health costs.

American culture likes to characterize retirement as a matter of individual responsibility. But this is nonsense. If you're not laboring yourself — which is the point of retirement — but you're still consuming goods and services, then by definition you're living off the fruit of other people's work. Social Security taxes and retirement portfolios and all the rest of it are just the paperwork by which retirees lay legal claim to the result of someone else's labor.

And this is a good thing: Every American should be able to enjoy a dignified and rewarding retirement.

But that means providing for retirement will always be a collective effort. When American government and American companies try to wriggle out from under that responsibility, the result can never be anything other than disaster.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?Today’s Big Question Europe may impose its own tariffs

-

‘Autarky and nostalgia aren’t cure-alls’

‘Autarky and nostalgia aren’t cure-alls’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Japan’s Princess Aiko is a national star. Her fans want even more.

Japan’s Princess Aiko is a national star. Her fans want even more.IN THE SPOTLIGHT Fresh off her first solo state visit to Laos, Princess Aiko has become the face of a Japanese royal family facing 21st-century obsolescence