The American retirement crisis is real

Here's what 401(k) apologists miss about the retirement crisis

Left-leaning groups and writers have been arguing for years now that America is looking down the barrel of a retirement crisis. The baby boomers are in the process of retiring, and a great many of them are just not ready for it.

But one liberal icon begs to differ. "[T]here's very little evidence for any kind of broad retirement crisis," Kevin Drum of Mother Jones argues, needling this "common view on the left, usually delivered with no evidence." So compiling data, he shows that 401(k)s and other retirement accounts have smoothly replaced traditional pensions, and that future income projections forecast a brighter future for retirees. It was all very interesting — conventional wisdom dispelled! The trouble is, it was also wrong.

Careful analysis shows that 401(k)s and individual accounts are still far inferior to traditional pensions for most people, and that the future projection relies on a lot of unrealistically rosy assumptions. Yet Drum's analysis is far from worthless — though flawed, it still manages to shed valuable light on the Byzantine operation of our retirement system.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Let's start where Drum does, with the idea that American retirement is already in a better position than it's given credit for. To back up this idea, Drum presents a chart that shows people over 65 making impressive income gains over the last few decades. But there's an immediate problem: He ignores that much of that income comes from working — i.e. the opposite of retirement. Earnings are the second-biggest source of income for seniors over 65 overall, and by far the biggest for those aged 65-69.

Of course, past trends don't have anything to do with the looming retirement crisis. So is Drum still right that the future remains bright for retirees? Let's go through a napkin sketch of the problem.

First, recall that for people to retire, they need to receive income without working. That means either through outside money transfers, like Social Security, or some sort of money hoard they can spend down over time, like pensions, 401(k)s, and other retirement accounts.

But several factors are combining to make future retirees' prospects here rather dim. In rough order of importance:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

1. Cuts to Social Security — mainly via an increase in the retirement age, which has gone from 65 to 66 and will soon increase to 67 — will reduce the amount of total income retirees can expect. (Social Security is the biggest source of retiree income.)

2. Defined-benefit pensions — which pay out much more reliably than defined-contribution plans — have been slowly dying over time.

3. The shift from centrally-managed pension funds to individual retirement accounts, like 401(k)s, means the risk burden has also been shifted to individuals, so savings need to be larger to compensate.

4. People are living longer on average, so a money hoard needs to be bigger to cover more years of retirement.

5. Interest rates have been extremely low and are likely to stay that way — meaning lower investment returns over time, and hence yet more needed savings.

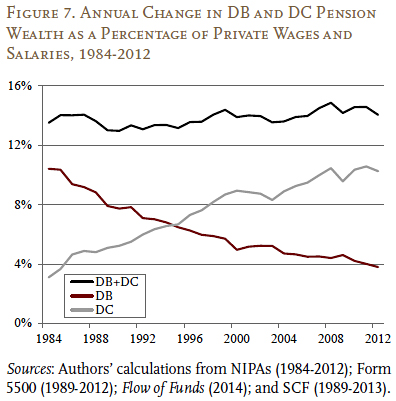

Against these issues, Drum presents the following chart (taken from a paper by the Center for Retirement Research) which shows that the rise in total individual retirement account assets (DC) has basically matched the decline in defined-benefit pension assets (DB). "In other words 401(k)s aren't a failure," he concludes.

But this chart is rather misleading. First, I should note that it does not show total savings increasing, as the trends I mentioned above make necessary. But more importantly, it obscures the fact that individual account savings are distributed vastly more unequally than pensions. More people have retirement accounts, but the pensions that do exist are spread far more evenly. Some 43 percent of families aged 32-61 have any sort of retirement account, and median account balance was $60,000 as of 2013. But the 90th percentile of retirement accounts had a balance of $274,000, and the top 1 percent had well over $1 million.

In other words, most of the 401(k) asset value is concentrated in a small minority of big accounts. That's why the Economic Policy Institute finds that pensions are a substantial source of income for many groups even as they slowly disappear, while retirement accounts are a tiny fraction for just about everyone — even rich people, because they have so many other sources of income.

The fact that most of the people with significant 401(k) savings don't particularly need them is not a coincidence. Like any nonrefundable tax break, 401(k)s pay out inversely to need, because the more money you make, the more you can write off your taxes. That makes for a hugely inefficient allocation of resources. Indeed, 401(k)s actively increase inequality: The top income quintile makes 63 percent of all income, but holds 74 percent of total 401(k) assets.

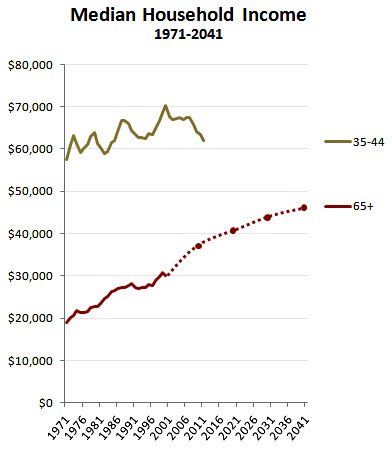

This finally brings me to the heart of Drum's case. All the above predict that, absent changes, senior income is going to decline relative to where it ought to be. But he says it will increase and presents this chart, constructed from an income projection done for the Social Security Administration (SSA) by the Urban Institute, as evidence.

Now, you can see that the chart really does show a steady increase in senior income over the next several decades. But it also relies on some questionable assumptions.

The original SSA projection predicts that retirement account participation is going to increase from about 60 percent among today's seniors to 80 percent when the first Gen Xers are 67, and that income from such accounts will more than offset the decline in pensions, increasing from about $2,000 today to $12,000, on average. It predicts that the homeownership rate among seniors will continue to increase, hence providing additional imputed rent. And it predicts that even despite the cuts, Social Security benefits will continue to increase overall, because they are calculated based on real income and the SSA foresees a roughly 1 percent increase in real income over time.

But these predictions seem wildly optimistic given the last 15 or so years. Less than half of families have any sort of retirement account, and the percentage has actually fallen by 4 points since 2001. Average account size has barely budged since 2000. The percentage of employers offering such accounts fell from 61 to 53 percent from 1999 to 2011. The homeownership rate has plummeted to the lowest level since 1965. And real median income has fallen by 7 percent since 1999.

Most of this is the result of the Great Recession, the failure to deal with the associated foreclosure crisis, and the ensuing crummy recovery. The SSA predictions basically assume that eventually, things will return to a pre-recession normal. But I see no reason to think the strong and broadly-shared growth of the 1990s will ever return, absent hugely aggressive economic stimulus that is nowhere in sight. Like Japan, we are probably going to be stuck like this for decades.

Luckily, Drum's approach for patching up the retirement system is on the right track. He proposes an increase in Social Security benefits for the bottom third of the income distribution by one third. Since Social Security is by far the best retirement policy, this is right and proper.

But since the SSA estimates are likely too optimistic, this should be strengthened. Previous cuts should be reversed; the Social Security retirement age should be reduced back to 65. Also, benefits should be increased across the board by about a third overall. Increases should be bigger for the bottom and middle, but everyone should be included, because means testing on the benefit side is bad. Instead, undesirable distributional effects should be fixed with higher taxes on the rich. The roughly $300 billion needed for such an increase can be had by slightly bumping the payroll tax, removing the cap — and if I had my druthers, axing the 401(k) and plowing the proceeds into retirement.

America is easily rich enough to provide a decent standard of living for everyone over 65. We just need to set aside traditional notions that retirement security should be the result of individual thrift.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Why quitting your job is so difficult in Japan

Why quitting your job is so difficult in JapanUnder the Radar Reluctance to change job and rise of ‘proxy quitters’ is a reaction to Japan’s ‘rigid’ labour market – but there are signs of change

-

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegations

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegationsIn the Spotlight Newsom called Oz’s behavior ‘baseless and racist’

-

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a party

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a partyThe Explainer Grab your friends and make a night of tackling the most boring tasks