How phage therapy works

British teenager is saved by experimental treatment suggested by her mum that could be used to fight superbugs

Scientists believe they may be on the brink of a major breakthrough in the battle against antibiotic-resistant superbugs after a British teenager made an unexpected recovery following an experimental new treatment.

Isabelle Carnell-Holdaway, a 17-year-old from Kent, was taken to hospital in 2017 with life-threatening complications arising from cystic fibrosis, a genetic condition that results in the lungs becoming clogged with mucus. After giving her a 1% chance of survival, doctors at Great Ormond Street Hospital attempted an untested treatment known as “phage therapy”, which uses genetically modified viruses to attack and kill deadly bacteria.

Against the odds, Isabelle made a full recovery. “It’s incredible medical science. It’s been a miracle,” says her mother, Jo.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Scientists are now conducting tests to find out if phage therapy is the next step in fighting antibiotic resistance worldwide. Here’s what we know so far.

Why is it in the news?

In 2017, after being plagued by two stubborn bacterial strains in her lungs for eight years, Isabelle underwent a double lung transplant. However, the procedure “left her with an intractable infection that could not be cleared with antibiotics”, The Guardian says.

The infection affected her surgical wound and then her liver, before nodules began pushing up through the skin on her arms, legs, and buttocks.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

After traditional antibiotics stopped working, the teen’s liver began failing and she ended up in intensive care, the BBC reports. She was kept at Great Ormond Street Hospital for nine months and was discharged only to return home to enter palliative, or end-of-life, care.

But her mother refused to give up and after researching alternatives on the internet, suggested attempting phage therapy.

The Great Ormond Street team contacted Professor Graham Hatfull of the University of Pittsburgh, who has spent more than two decades “enlisting students to help him amass the world’s largest collection of bacteriophages” - viruses that prey solely on bacteria, Wired reports.

The Guardian says that Hatfull and his colleagues “tested thousands of combinations” of phages in petri dishes before identifying three phages that could reverse the infection. Two of them were able to inflict damage to the bacteria while the third was able to destroy the infection entirely.

Isabelle returned to Great Ormond Street and was “given the cocktail twice daily via an intravenous drip and on her skin”, the newspaper says. Six weeks later, a liver scan revealed the infection had all but vanished and she had not experienced any side-effects.

Hatfull has called the outcome “brilliant”, adding that he “didn’t think we’d ever get to a point of using these phages therapeutically”. Other experts have described the case as “enormously exciting”, says the BBC.

How does it work?

Nova reports that scientists first used phage therapy in the early 1900s, but it was eclipsed by the discovery of antibiotics, which are much easier to use.

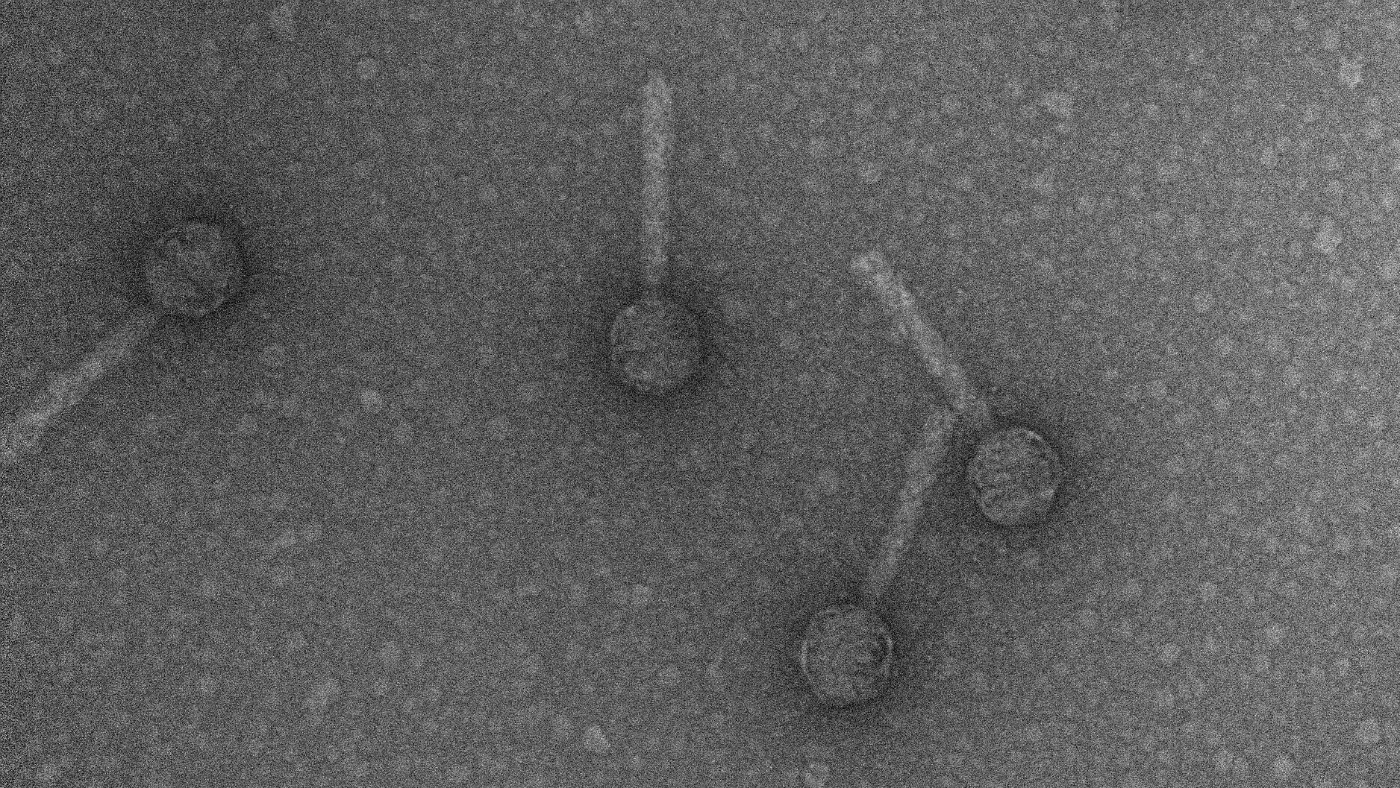

Phages, also known as bacteriophages, are a type of naturally occurring virus that infects bacteria rather than the body’s own cells, according to the BBC. They land on the surface of bacteria and inject their own genetic code into it.

The broadcaster says this effectively “hijacks the bacterial cell”, turning it into a phage factory until the viruses eventually burst out of the cell and destroy it. The BBC suggests that phages are the “microbial embodiment” of the adage “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”.

However, only certain phages naturally have the ability to destroy bacteria in this way. Of the three that were selected for Isabelle’s treatment only one - dubbed Muddy - exhibited this characteristic, known as a lytic lifecycle. The other two - ZoeJ and BPs - were able to enter the bacteria but went dormant once inside.

As a result, Hatfull needed to toggle what Wired describes as their “snooze button” in order to send them into “phage rage” mode to help the patient. To achieve this, genetic engineering was used to remove the repressor gene from ZoeJ and BPs, and with that stretch of DNA gone they could completely destroy bacteria from the inside like Muddy.

“And because the scientists hadn’t added any genes, merely deleted some, the phages weren’t subject to the European Union’s regulations around GMO therapeutics,” the science site adds.

Is it the solution to antibiotic resistance?

The BBC says this is “the big question”, but adds that “at the moment there is no clear answer”.

Isabelle’s consultant, Helen Spencer, says that the case - and the rise of antibiotic resistance - has fuelled interest in phage therapy, but adds that there are significant logistical limitations to rolling out the largely untested technique in mainstream medicine.

“I had a sense that this collection was enormously powerful for addressing all sorts of questions in biology” but “we’re sort of in uncharted territory”, she said.

The Guardian reports that the main obstacle for doctors is finding the right phages for each patient. “In the future, scientists hope it may be possible to conduct automated searches of phage libraries to identify personalised treatments,” it writes.

In the meantime, the treatment that saved Isabelle will need to be extensively tested before it can be more widely used.

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion