Ready meals explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

The rise of so-called TV dinners has revolutionised our culinary habits

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world.

The ready meal in 60 seconds

A ready meal is a type of meal, often for one person, that can be cooked in its packaging and requires little to no preparation.

Although these so-called TV dinners were available in the US from 1940s - usually in the form of a type of meat, with a side of vegetables and potatoes - it wasn’t until the following decade that the idea really took off.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Consumers in the UK were slower to embrace ready meals, "largely because domestic freezers did not become the norm until the late 1960s and early 1970s", said BBC. But "chilled ready meal sales rose throughout the 1980s and the arrival of microwaves in the domestic kitchen only increased them further", the broadcaster adds.

Indeed, such is their popularity that the aluminum cooking tray designed for use with the first ready meals has since been inducted into the Museum of American History, a museum that "preserves and displays the heritage" of the country.

Nutritionists and scientists have voiced concerns about these meals, however. A 2013 study outlined in a paper in the British Medical Journal found that of 100 supermarket ready meals analysed, not one fully complied with nutritional guidelines set out by the World Health Organization.

Despite such concerns, British consumers buy more than three million ready meals every day, according to Good Housekeeping magazine. That equates to around half of all ready meals sold in Europe, added the Daily Mail.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How did it develop?

The first ready meal was manufactured in 1945 by Maxson Food Systems and was called the "Strato-Plate". However, the meals were only sold for consumption on airplanes by military and civilian passengers, and never made it to the retail market, according to the US Library of Congress.

The ready meal as we recognise it today was invented by an American food company called Swansons. The Swanson family say the idea first arose in 1953, when the company was left with a 260-tonne surplus of turkey after Thanksgiving, the Smithsonian magazine reports.

The two brothers behind the firm - Gilbert and Clarke Swanson - hit upon the idea of packaging up the surplus turkey with all of the other components of the traditional American dinner; cornbread dressing, frozen peas and sweet potatoes. This was then packed into the same type of aluminium trays as those used to serve food by airlines, which acted as both the tray to cook the frozen meal and a plate off which to eat it.

Gerry Thomas, a salesman at the company, has said that he came up with both the idea and the name "TV dinner", but both the Swanson family and some staff have refuted that claim.

The new meals were a huge success, with ten million reportedly sold in the first year of production, according to The Independent.

As domestic freezers became the norm in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and more women entered the workforce, ready meals increasingly became a "a relief from domestic labour", according University of Manchester sociology professor Alan Warde.

The popularity of this easier dining option grew over following two decades, although the form of ready meals changed, with frozen food becoming more popular than the original tray-based dinner. During this period, famous products including Findus Crispy Pancakes and Birds Eye Potato Waffles were launched in the US, alongside frozen desserts such as Wall’s Viennetta and Birds Eye’s Arctic Roll.

Ready meals underwent another evolution in the late 1980s, with consumers increasingly turning to chilled ready meals as what was perceived as being a fresher and healthier alternative to the frozen options.

One of the most popular of these chilled meals in the UK was the Marks and Spencer chicken kiev, launched in 1979 for £1.99, and designed by product developer Cathy Chapman.

According to The Daily Telegraph, the kiev was intended to be "a sophisticated alternative to the TV dinner" and "the kind of meal that a working middle-class woman could serve to friends". To this day, it is used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) as one of the products used to calculate inflation.

The BBC says that by 2012, "chilled ready meal made up 57% of the UK prepared meals" in a market worth £2.6bn. In the US, the frozen food industry is worth $22bn (£17.2bn) per year, with Americans consuming an annual average of 72 frozen meals each year, according to statistics released by the American Frozen Food Institute.

How did it change the world?

The ready meal has "revolutionised the way that we eat", making it possible to "continue the culture of social eating" as the world gets faster and busier, said Artefact.

As the magazine notes, "home-cooked meals and slow dining are no longer a central part of the day", with the ready meal providing a convenient alternative.

The rise of the ready meal has also allowed for the reallocation of "time previously spent in the kitchen to other forms of personal development", especially among women, according to research by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In addition, the launch of pre-prepared meals triggered an expansion in the culinary horizons of consumers, allowing people to become "more adventurous when it came to food", said the BBC. As Artefact magazines notes, the ready meal offers a "budget-friendly way of experimenting with taste palettes".

However, the MIT study also found that the rise of the TV dinner coincided with an increase in the "informality of dinnertime rituals", in which families moved "away from the dining table and in front of the television". The researchers conclude that communication over mealtimes has been "eroded by the appearance of frozen food".

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. Zero

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. ZeroIn Depth The technology on which you’re reading this article only works because of zero

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. Money

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. MoneyIn Depth Millennia of civilisations have used mediums of exchange ranging from seashells and cows to bitcoin and cash

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. Ecology

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. EcologyIn Depth Scientific ecology can be traced back to Charles Darwin and considers living things and their environment

-

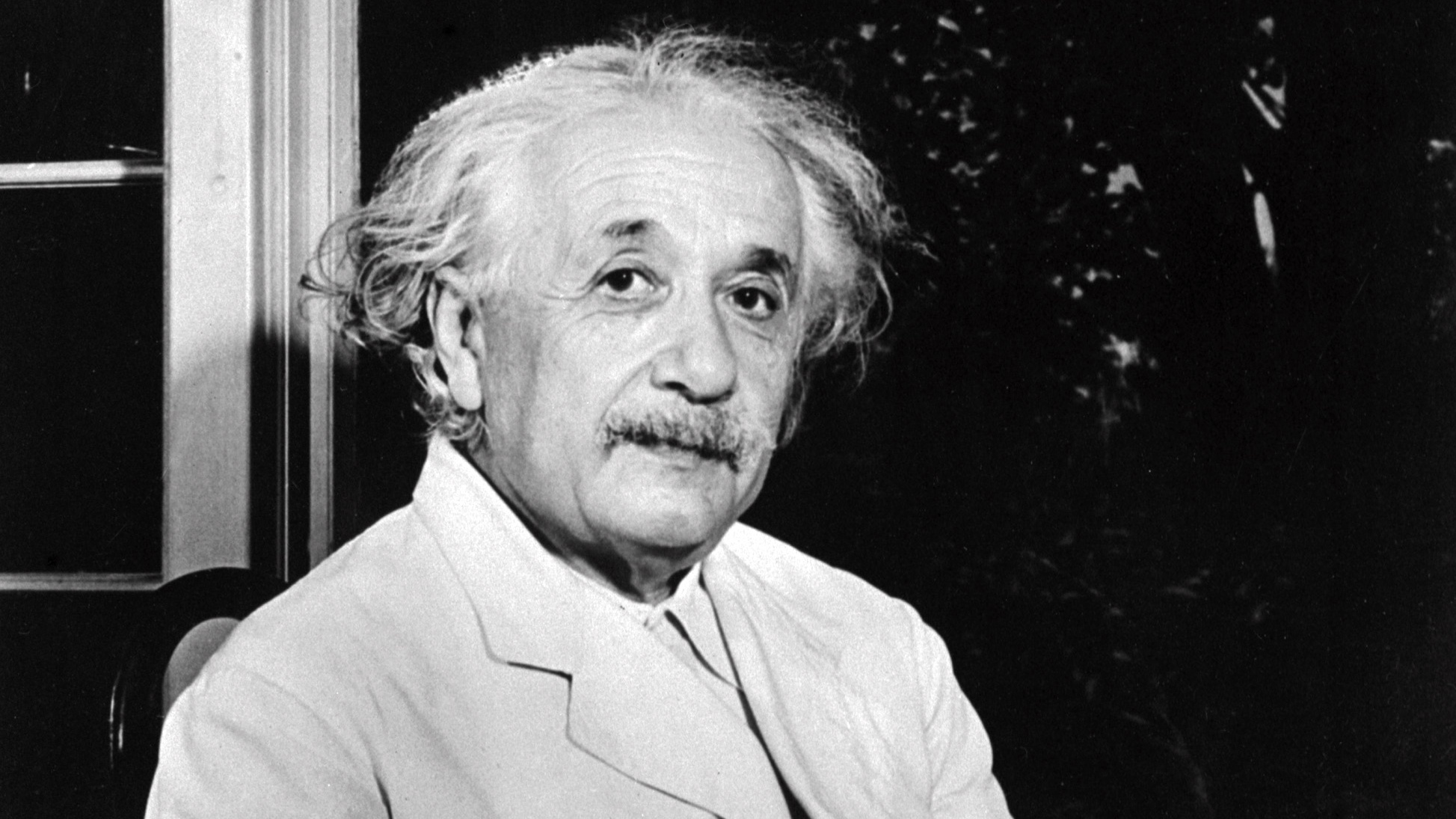

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. Relativity

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. RelativityIn Depth Einstein’s theory remains ‘most important in modern physics’

-

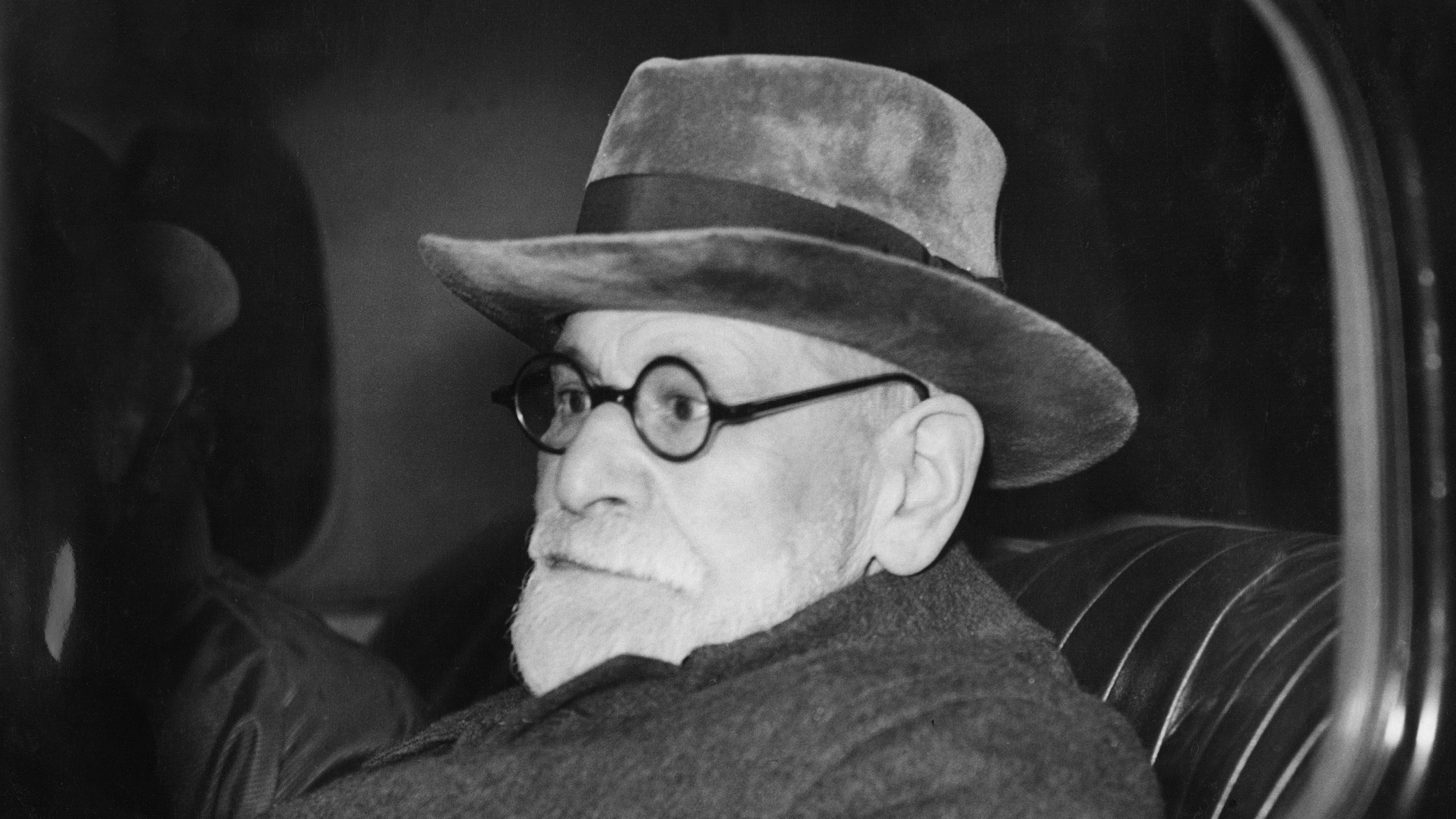

52 ideas that changed the world - 46. The unconscious mind

52 ideas that changed the world - 46. The unconscious mindIn Depth The theory of an obscured section of human consciousness has hooked psychologists for centuries

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. Writing

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. WritingIn Depth Writing is the foundation of history, great literature – and this article

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. Monogamy

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. MonogamyIn Depth The roots of monogamy have more to do with evolution than romance

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheel

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheelIn Depth The wheel might seem simple, but it took humans a long time to figure it out