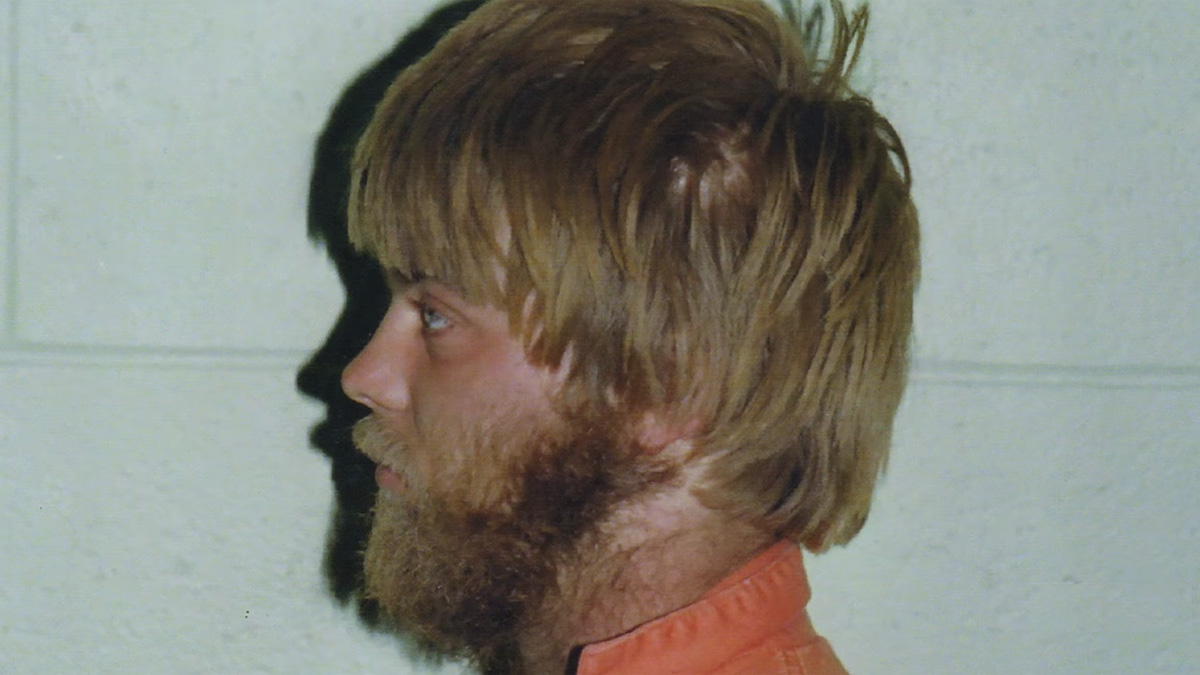

Making a Murderer: why everyone is talking about Steven Avery

Armchair sleuths are hooked by the story of Steven Avery, but why is it so popular?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Netflix's Making a Murderer is the latest true-crime series to get viewers hooked, with some calling it the new Serial - but who is Steven Avery and why is his story so popular?

The ten-part series was first made available on Netflix on 18 December, in the heart of the festive season, and has since attracted many thousands of viewers. It recounts the story of Steven Avery, a Wisconsin man who was jailed in 1985 for the sexual assault and attempted murder of Penny Beerntsen but exonerated 18 years later. Two years after that, he was accused and convicted of the murder of Teresa Halbach.

The series covers both cases in forensic detail, from the blood swabs taken from an abandoned SUV to aerial photographs, and the complex machinations of the police investigations and the court cases that followed. It also examines how DNA evidence was used to exonerate Avery from the first murder and how the second charge came while he was making a $36m (£24.6m) compensation claim.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some commentators have called Making a Murderer the television equivalent of the Serial podcast, which re-opened the 1999 case of the murder of a high-school student in Baltimore and became the most popular podcast in history. Others have compared it to Jinx, HBO's series about the alleged murders of real-estate heir Robert Durst.

But why do true-crime shows such as Making a Murderer fascinate viewers?

Christopher Hooton in The Independent says the genre isn't anything new, pointing to 1988's documentary The Thin Blue Line and subsequent shows such as The Staircase and West of Memphis. But Hooton says the transference of these stories into the mainstream of "'Trending Now', 50,000 shares and 'Must Read'" is new.

Hooton gives a number of reasons for the popularity of shows such as Making a Murderer, suggesting the level of detail provided and the distribution format allowing for binge-viewing are important. But the key thing, he adds, is that "people love justice and they love to see the truth out" and that it's now "easier than ever for the masses to funnel their outrage" at authorities.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Viewers have been hooked by the possibility that Avery may be innocent, says Tim Robey in the Daily Telegraph. Since the show aired, more than 300,000 people have signed a change.org petition demanding his pardon and calling the prosecution "an abomination of due process".

Making a Murderer "gets us through the door" with the whodunit aspect and provides plenty of fodder for armchair sleuths, he adds. Yet it also exposes the gaping holes in the prosecution's case against Avery.

Robey says "it's in forcing us to sift the evidence and realise the complexity involved in reaching a conclusion" that these shows become so compelling.

Stephanie Merry at the Washington Post is less convinced. She says Making a Murderer "leaves out or glosses over crucial facts", including Avery's past conviction for animal cruelty.

She admits the filmmakers say they were not really concerned with Avery's innocence or guilt but wanted to document the legal process, which is what they do. But what made Serial so revolutionary, argues Merry, and what is absent from Making a Murderer, is that it exposed its own "reportorial bias" in the process.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

February TV brings the debut of an adult animated series, the latest batch of ‘Bridgerton’ and the return of an aughts sitcom

February TV brings the debut of an adult animated series, the latest batch of ‘Bridgerton’ and the return of an aughts sitcomthe week recommends An animated lawyers show, a post-apocalyptic family reunion and a revival of a hospital comedy classic

-

The 8 best hospital dramas of all time

The 8 best hospital dramas of all timethe week recommends From wartime period pieces to of-the-moment procedurals, audiences never tire of watching doctors and nurses do their lifesaving thing

-

The 8 best horror series of all time

The 8 best horror series of all timethe week recommends Lost voyages, haunted houses and the best scares in television history

-

The 8 best comedy movies of 2025

The 8 best comedy movies of 2025the week recommends Filmmakers find laughs in both familiar set-ups and hopeless places

-

The best drama TV series of 2025

The best drama TV series of 2025the week recommends From the horrors of death to the hive-mind apocalypse, TV is far from out of great ideas

-

The 8 best drama movies of 2025

The 8 best drama movies of 2025the week recommends Nuclear war, dictatorship and the summer of 2020 highlight the most important and memorable films of 2025

-

The 8 best comedy series of 2025

The 8 best comedy series of 2025the week recommends From quarterlife crises to Hollywood satires, these were the funniest shows of 2025

-

A postapocalyptic trip to Sin City, a peek inside Taylor Swift’s ‘Eras’ tour, and an explicit hockey romance in December TV

A postapocalyptic trip to Sin City, a peek inside Taylor Swift’s ‘Eras’ tour, and an explicit hockey romance in December TVthe week recommends This month’s new television releases include ‘Fallout,’ ‘Taylor Swift: The End Of An Era’ and ‘Heated Rivalry’