Stephen Bayley on Sir Terence Conran

The cultural commentator reflects on the impact his friend and fellow design powerhouse has had on British life

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

My favourite account of the Conran world view remains: ‘The problem with Terence is he wants the whole world to have a better salad bowl.’ When I heard art dealer John Kasmin say that, I was struck both by its nice wit and the fine ambition it illuminated. It also confirms a design/food association that, for Terence, is fundamental.

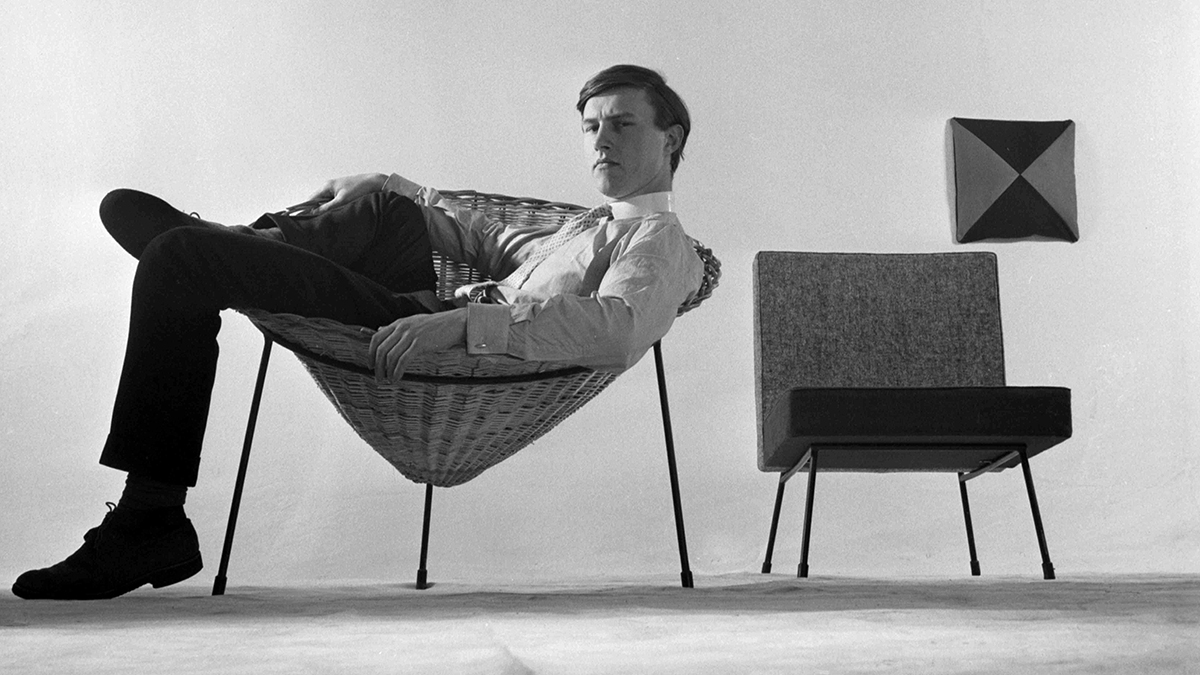

Terence’s first, very junior design job was at the Festival of Britain in 1951, the year Elizabeth David published French Country Cooking. Mrs David’s books were sauce for Terence. The vileness of the era’s British food was a creative stimulus. Rissoles sat, in grim pools of fat, in depressing contrast to the bright colours and strong flavours of Mrs David’s love letters to garlic, oil and lemon.

Cooking and designing are inseparable in Terence. It’s not about recipes or drawings, but attitudes and romance. Elizabeth David was as much part of post-war neo-romanticism as Terence hammering away at modern furniture in a Notting Hill flat. Against a backdrop of bomb damage and rationing, her books were like a sketch for a future Conran restaurant. Eat garlic and you could pretend to be on the Côte d’Azur. Make modern furniture and you could imagine you were in Paris. Cooking and design are escapes from suburban mediocrity. Despite the aroma of Chelsea, Terence was born in Esher.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

France was always the beau idéal: people ate better there, had more style. Conran did not invent France, but artfully sold an Englishman’s interpretation of its art de vivre (‘lifestyle’ is a term he detests). It was a short step from selling that better salad bowl to serving frisée aux lardons in his own restaurant.

Food and design have equivalences – in function/nutrition, delight/pleasure – and restaurants are places where people learn about design. The gastronome Brillat-Savarin said, ‘Tell me what you eat and I will tell you who you are.’ You could also assert: tell me where you eat and I will tell you who you want to be. Terence intuited this at several levels.

To the recently blitzed British, France suggested a dream world. In their 1957 book Plats du Jour, Patience Gray and Primrose Boyd said, ‘We know that many people live in far from modern homes.’ Their remedy was to go to Madame Cadec (a shop, not a brothel) in Soho to buy white French porcelain. Terence did so. Then, in 1964, he opened Habitat – a glorious mix of vernacular and modern, white china and Braun appliances – in response to frustrated yearnings for exoticism in cooking and interior design.

Terence’s France combined style with practicality. His favourite dish? Poulet demi-deuil, a telling blend of simplicity and sophistication: a good Bresse chicken with subcutaneous slices of black truffle, as if in half-mourning. A designed chicken.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

His 1985 acquisition of Chelsea’s Michelin House was the ultimate homage to France, uniting great architecture, food, wine, cars and shopping. With a nice symmetry, its Bibendum restaurant became Elizabeth David’s favourite place to dine in her last years.

One of Terence’s best observations links food, design and hedonism. A magnum, he told me, makes even vin ordinaire a luxury. ‘Nunc,’ according to Horace, Michelin and Terence, ‘est bibendum.’ Now is the time for drinking.

STEPHEN BAYLEY first worked with Sir Terence Conran in 1981 on the Boilerhouse project at London's V&A, which evolved into the Design Museum. They co-authored the 2007 book, Design: Intelligence Made Visible. They often collaborate on lunch, too; stephenbayley.com; conran.com

-

Touring the vineyards of southern Bolivia

Touring the vineyards of southern BoliviaThe Week Recommends Strongly reminiscent of Andalusia, these vineyards cut deep into the country’s southwest

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Elon Musk’s starry mega-merger

Elon Musk’s starry mega-mergerTalking Point SpaceX founder is promising investors a rocket trip to the future – and a sprawling conglomerate to boot