Country house parties: Charleston and the Bloomsbury Group

Charleston Trust director Alistair Burtenshaw on what makes the influential group's Sussex home so magical

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One of the key questions I must ask myself as director of the Charleston Trust is what is it that should make somebody want to come here? My sense is that it is the collective whole. Its famous residents made it a place of refuge, ideas, inspiration, rebellion and exploration. Today it is still a place of such composite parts, which feed into another key aspect: Charleston's powerful sense of place. It is a house that witnessed radical discussion of the way in which people live their lives.

Its relevance is not only historical though – it is still contemporary, as people continue to explore their place in life and the world within the bounds of this wonderful setting. Indeed, I always feel a very strong sense of place here at Charleston, standing by the pond in front of the house in the middle of the South Downs.

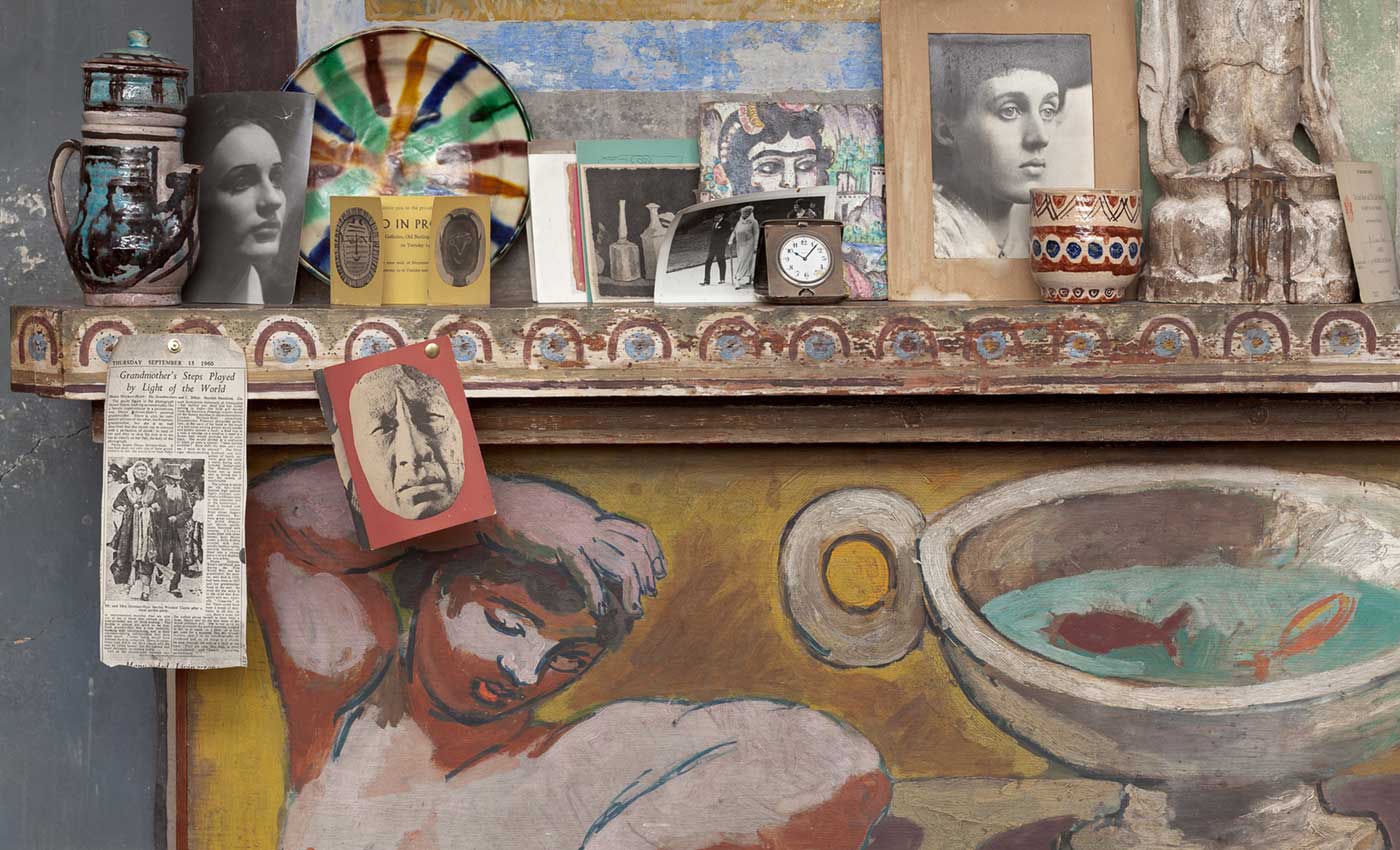

Purely in terms of the house itself, it is the only wholly intact Bloomsbury interior anywhere in the world. So it possesses a special connection with the ideas and the art of this incredible group. Anyone interested in Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and the wider group should absolutely visit Charleston, and come and explore for themselves.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Architecturally, Charleston is a 17th-century farmhouse, very much in the local vernacular. It is well set in its place, now the South Downs National Park, in the grounds of the historic Firle Estate. The house was discovered by Virginia Woolf's husban, Leonard Woolf. The pair used to see it on their walks from Asham – a house they had used as a holiday home, now sadly demolished. At the time [during the First World War], Vanessa Bell was seeking a refuge for Duncan Grant and David Garnet, both conscientious objectors.

Back then the only acceptable option for pacifists was to work the land. Grant and Garnet had already failed to avoid conscription in Norfolk, so the decision was made to move down to Charleston. This is when Virginia Woolf's wonderful letters to Vanessa Bell appear in May 1916, which describe Charleston and its overrun state. Virginia Woolf thought that Vanessa Bell could make it something very special. In October 1916, five months later, Bell, Grant and Garnet moved here with Bell's children. There was of course the onset of winter to contend with and it must have been extremely cold and difficult. They started transforming the house immediately, but Charleston was not their permanent home until later.

The transformation was extensive and radical. Charleston was full of Edwardian and earlier wall coverings, so most of the interiors were white washed to create a blank canvas. The flowers painted around the window of Clive Bell's study were the starting point. In terms of the general objectives of the transformation, it is important to understand that they never intended the house to be finished, rendering the transformation a permanent work in progress, with an important wartime sense of make do and mend. In a similar vein, there was an unpretentious emphasis on the functionality of pieces – they were there to be used.

Furniture was decorated but above all else it was used. They were adamant about this arrangement. I think this helped develop a characteristic of the house that has most appealed to me since I came here 25 years ago and that guests always note – this wonderfully eclectic mix, a sort of bohemian, localised Sir John Soane's Museum. There is Staffordshire Pottery next to the Renaissance copies the group would paint. One is left with an impression of artistic harmony and partnership throughout the house. Indeed alongside each other, Vanessa Bell and Grant would often paint the same subjects. I encourage guests to observe the fascinating similarities and differences in paintings that were produced at the same time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Another thing I think is interesting about the transformation and their philosophy as a group is the status of design. Today's audiences visit with a pre-formed idea of what constitutes design. Design is a thing that we talk about in and of itself: for example, we have the Design Museum and fashion 'designers'. But at the time Vanessa Bell and Grant decorated Charleston, the furniture, furnishing and upholstery were really very radical. Looking at the fabrics and the use of white, shows how astonishingly ahead of their time they were. The integration of ceramics, textiles, fabrics, decorated wall surfaces and decorated interiors was unusual, especially given this was being done 'at home', with the final goal being a space of refuge and comfort. They certainly struck this balance and I do not think anyone gets the sense that Charleston is somehow overly designed.

It is also worth mentioning those the group admired from further afield. They were hugely inspired by the likes of Matisse and Picasso and followed what was happening in France at the time very closely. The Bloomsbury Group looked outwards and were influenced by Europe and the wider world – of course, they now have an influence even further afield. The balance, then, was between being grounded in place – a rural farmhouse in the South Downs – while still being open to the borderless ideas of the time. It was this attitude that propelled the group into the centre of developing these ideas. Take Maynard Keynes, who wrote The Economic Consequences of the Peace in his room and the garden at Charleston. Virginia Woolf, of course, lived nearby, first at Asham House and then at Monk's House and was a regular visitor, much like E M Forster, Lytton Strachey and T S Eliot.

After a time it became clear they were actors in the birth of Modernism, that bold idea of saying goodbye to the Victorian era. It is said that you could hear the guns of the Western Front during the First World War from Charleston. Tea sets would rattle. To those who witnessed it here, it was audible evidence of the previous age coming to a close and a new, far bleaker era dawning. It must have felt very proximate, especially given that among them were conscientious objectors. Of course, the Second World War followed and the story was much the same. But the house stayed on as over time Bell and Grant made it their permanent base. Bell died here in 1961 and Grant lived here until just before his death in 1978.

ALISTAIR BURTENSHAW is director of the Charleston Trust. The Charleston Small Wonder Short Story Festival (27 September to 1 October) runs annually; charleston.org.uk