Who was Marie Curie?

Pioneering physicist and chemist voted most influential woman in history in BBC poll

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Marie Curie was the most influential woman in world history, ahead of Rosa Parks, Margaret Thatcher, Emmeline Pankhurst and the Virgin Mary, according to a BBC poll.

Polish-born French scientist Curie revolutionised science’s understanding of radiation and cancer, and was the first person to win two Nobel prizes - one for physics and one for chemistry. Her discoveries precipitated the creation of multiple cancer treatments and the introduction of x-ray technology in medicine.

Those achievements have been honoured by readers of the BBC History Magazine, who selected her as the poll winner from 100 famous women picked by experts from ten fields. Curie’s nominee, Patricia Fara, president of the British Society for the History of Science, said: “The odds were always stacked against her. In Poland, her patriotic family suffered under a Russian regime. In France, she was regarded with suspicion as a foreigner – and of course, wherever she went, she was discriminated against as a woman.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Who is Marie Curie and why was she so important?

Maria Sklodowska was born in 1867 in Warsaw, Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. She was the fifth and youngest child of teachers Bronislawa and Wladyslaw Sklodowski.

At the age of 17, Maria became a governess to help pay for her older sister Bronia to attend medical school in Paris. The Marie Curie Foundation website says that “when her sister offered her lodgings in Paris with a view to going to university, she grasped the opportunity and moved to France in 1891”.

She enrolled at the French capital’s Sorbonne University, where she read both physics and mathematics, graduating with two degrees in 1894.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

During her time at the Sorbonne, she met Pierre Curie, a highly respected researcher with similar interests to Curie. The pair married in 1895.

Radioactivity

After graduating, the couple became research workers at the School of Chemistry and Physics in Paris. Here, they followed up on fellow physicist Henri Becquerel’s report of invisible rays emitted from uranium ores.

LiveScience reports that Marie Curie “decided to use Pierre’s instruments” to “show that the effects of the rays were constant even when the uranium ore was treated in different ways”.

This, in effect, confirmed Becquerel’s observation that higher concentrations of uranium in an ore resulted in more intense rays, and Curie suggested a revolutionary hypothesis: that the emission of these rays was an atomic property of uranium.

LiveScience adds: “If true, this would mean that the accepted view of the atom as the smallest possible fragment of matter was false.”

Curie decided to test all known chemical ores to see if they behaved similarly. She and her husband became intrigued by pitchblende, a chemical ore often left over as a waste product from factories of the era. They found that it gave off almost 330 times as much radiation as pure uranium ore, which convinced Curie that it contained a new radioactive element not yet discovered.

The pair sifted through tons of pitchblende - exposing them to dangerous doses of radiation - to extract the hypothetical substance. In July 1898, the Curies published a paper announcing their discovery of polonium, a highly radioactive element that she named after her native country, Poland.

Later that same year, they announced the discovery of another radioactive element, radium, which had also been extracted from pitchblende.

In 1903, Marie and Pierre were awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for their discoveries. In 1911, five years after Pierre’s death, she was awarded a second Nobel, this time in chemistry.

Legacy

In later years, Curie not only continued to justify her reputation as a pioneering scientist but also became a humanitarian figure. During the First World War, she suspended her studies and organised a fleet of portable x-ray machines for doctors on the Front, aiding the diagnosis of injured soldiers. She often toured the battlefields herself.

In the late 1920s, Curie started suffering medical problems, probably caused by her exposure to radioactive materials, says LiveScience. She died on 4 July, 1934, of aplastic anemia, a blood disease often caused by radiation exposure.

During her extraordinary career, she was so revered that a female cancer hospital in north London asked to use her name for their facility, which later grew into the Marie Curie cancer charity. She and her husband are also immortalised in the Curie (Ci) unit of radioactivity, in the periodic element curium (Cm), and as the asteroid 7000 Curie.

But for some, her most remarkable achievement is her role as a pioneering woman in science in the face of constant discrimination.

Despite her success, Curie faced “great opposition from male scientists in France, and she never received significant financial benefits from her work”, says the BBC.

In an article about Curie for The Independent, Open University professor Monica Grady adds: “It just seems such a shame that 150 years after her birth, we still haven’t got the role of women in science and engineering at the level of attainment that means we can stop talking about it.”

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The truth about vitamin supplements

The truth about vitamin supplementsThe Explainer UK industry worth £559 million but scientific evidence of health benefits is ‘complicated’

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

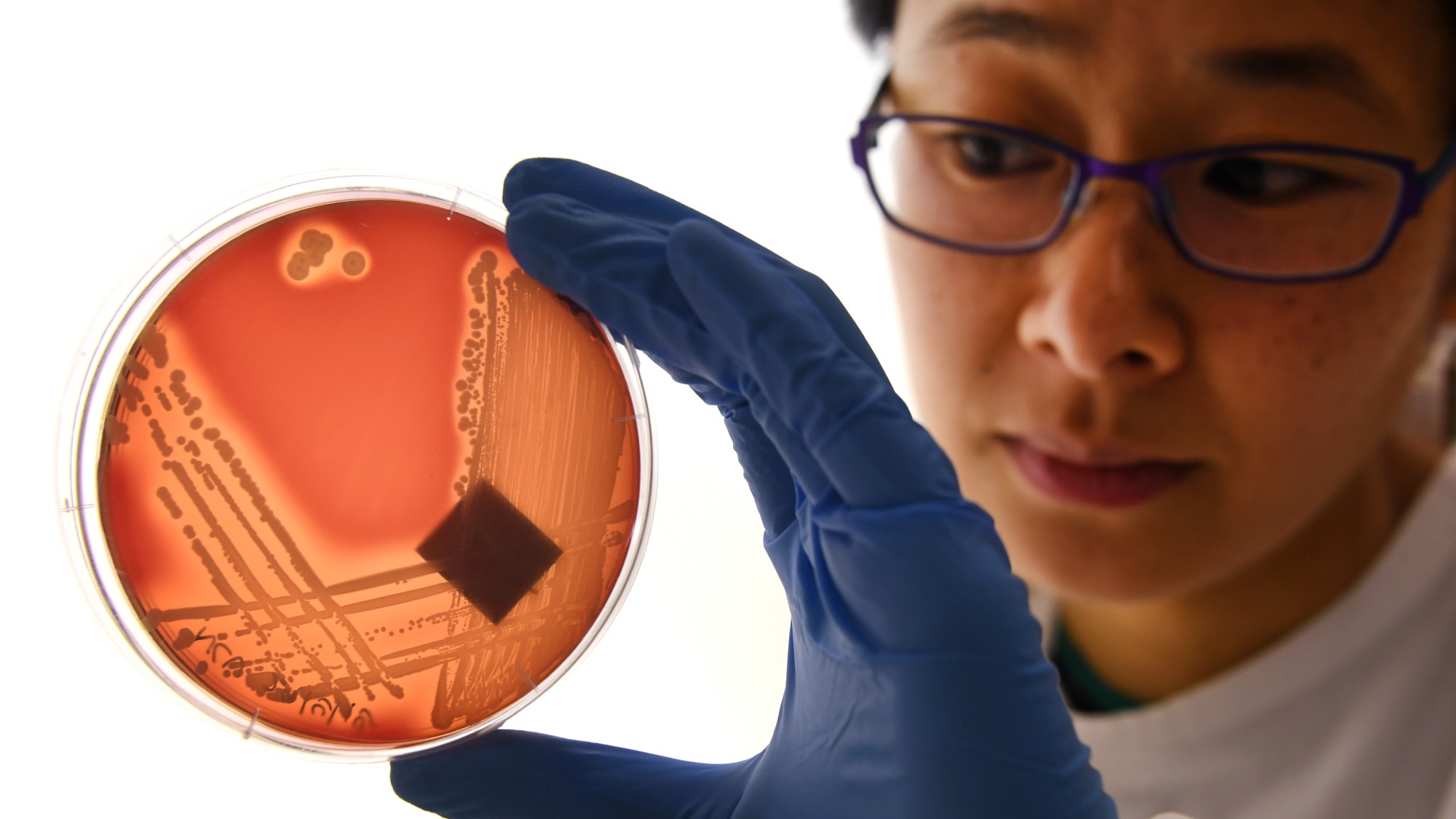

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugs

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugsThe Explainer Antimicrobial resistance is causing millions of deaths. Could a faeces-filled pill change all that?

-

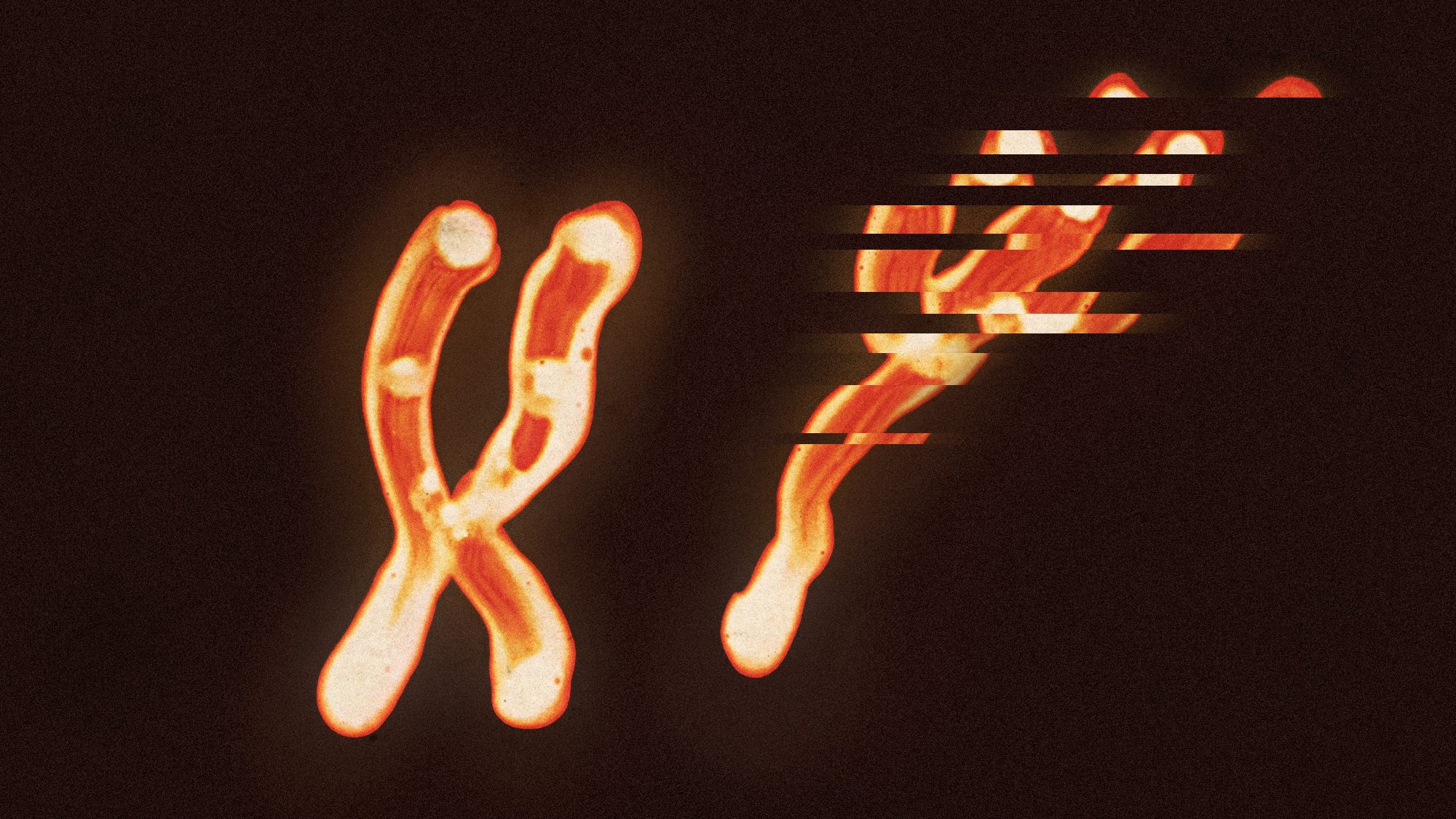

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for it

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for itUnder the radar The chromosome loss is linked to cancer and Alzheimer's

-

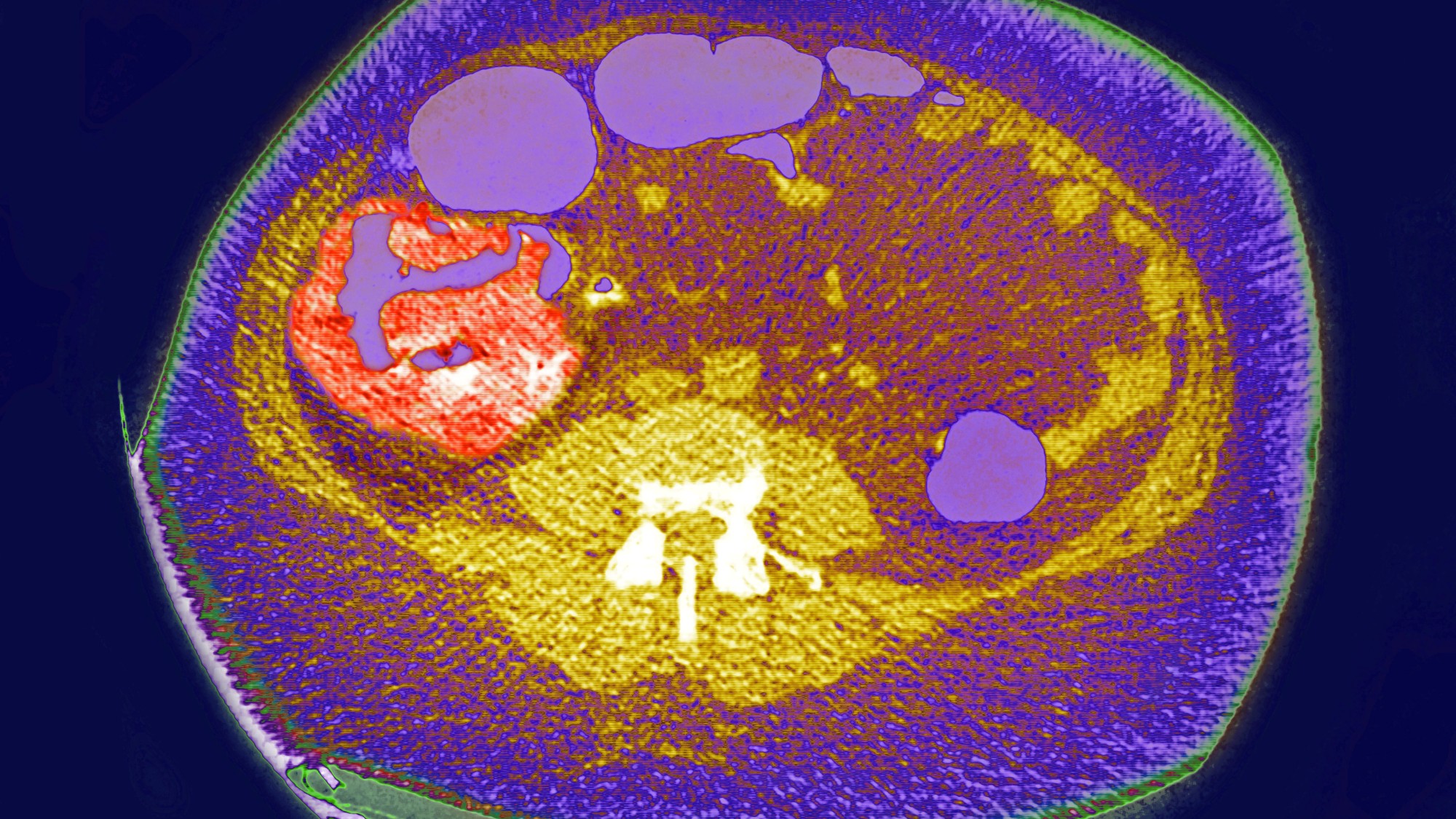

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young people

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young peopleUnder the radar Most exposure occurs in childhood

-

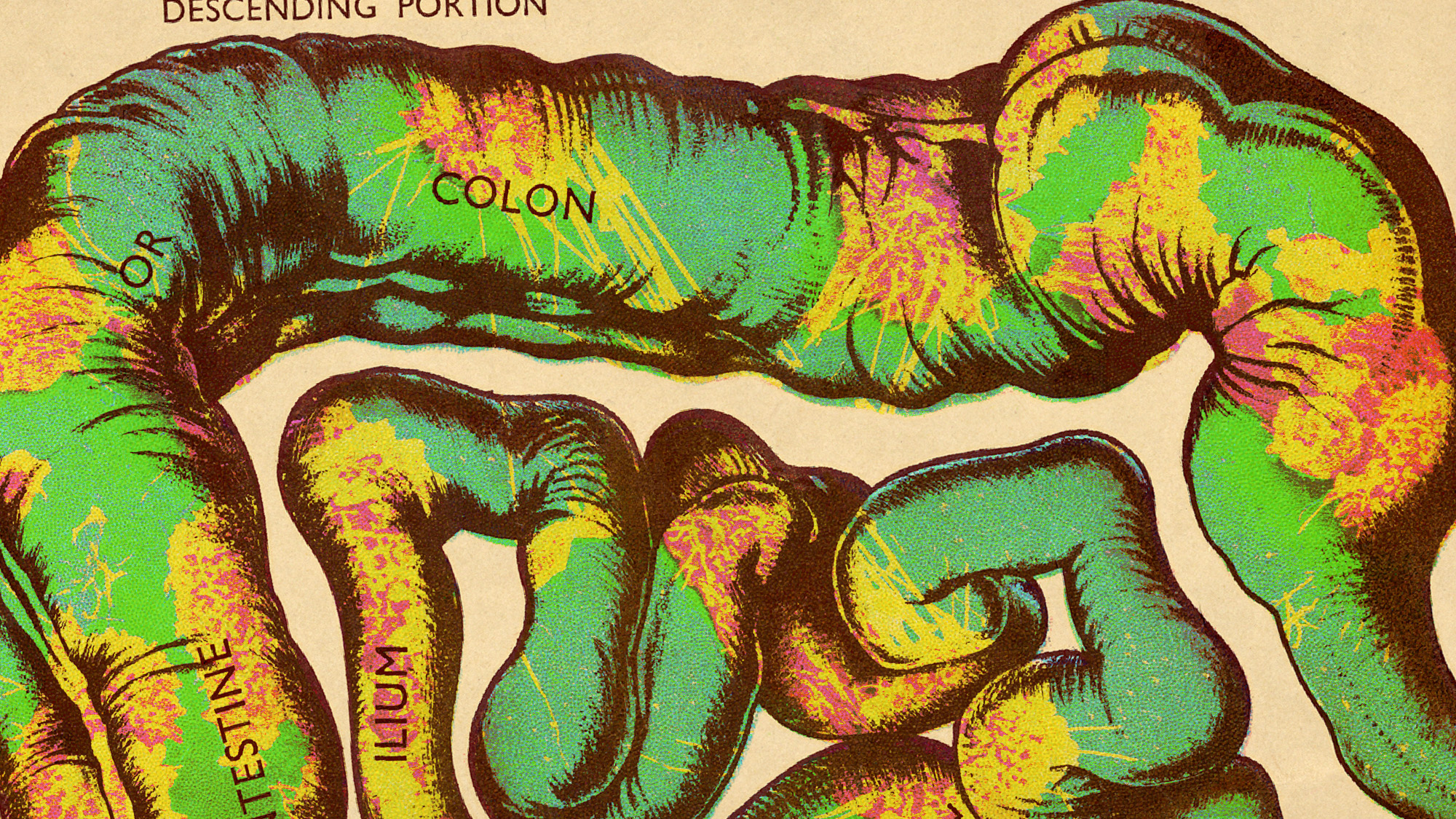

Why are more young people getting bowel cancer?

Why are more young people getting bowel cancer?The Explainer Alarming rise in bowel-cancer diagnoses in under-50s is puzzling scientists

-

Five medical breakthroughs of 2024

Five medical breakthroughs of 2024The Explainer The year's new discoveries for health conditions that affect millions