This is life in Afghanistan since the Taliban takeover

Hunger, drugs, and restrictions on women haunt the nation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's been a chaotic nine months since the Taliban seized control of Afghanistan — the economy is in a free fall; methamphetamine production has exploded; the United Nations estimates that half of the country's population is suffering from acute hunger; the rights of women are being eroded; and there's been an increase in violent attacks by the Islamic State. Here's everything you need to know:

What is going on with Afghanistan's economy?

Before the Taliban took over, about 80 percent of the government's budget came from foreign aid. Now, that's a trickle, with some countries suspending financial assistance altogether and others cutting back. The Taliban said it intends to boost domestic revenue by modernizing financial systems and ending government corruption, and has promised to provide partial forgiveness of back taxes and reduce income tax.

In Kabul, there are an estimated 120,000 small businesses, The Washington Post reports, and owners are struggling to sell merchandise and pay their employees. Many people lost their jobs once the Taliban took over — including teachers — and customs fees are now higher, forcing shopkeepers to raise their prices. In the most extreme situations, people who are desperate for money are selling their daughters into marriage or their own organs, with one man in Herat receiving $4,500 for his 15-year-old son's kidney. It's illegal to sell organs in Afghanistan, but the man told The Wall Street Journal he needed the money to pay off his debts.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Is the economic crisis fueling other illicit industries?

For decades, Afghanistan was known for producing opium, shipping out about 80 percent of the world's supply. In the last few years, there's been a shift to methamphetamine production, with experts, former government officials, and drug traders telling the Post there are now hundreds of meth labs around Afghanistan.

There is a plant called ephedra that grows wild in Afghanistan, and it's a natural source of meth's main ingredient; because it's so easy to find, more people are making and selling meth as a way to make money. The Taliban issued a ban several weeks ago prohibiting the growing, production, and distribution of illegal drugs, but most experts do not think they will go after manufacturers, noting that in 2019, it's estimated the Taliban received $113 million in tax revenue off of the opium trade.

"A significant part of the Taliban's revenue comes from taxing illicit commodities, and drugs is one of those," Andrew Cunningham of the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction told the Post. "It is impossible to provide even the most basic of services unless there's money coming into the government coffers. So, for them to do something about a drug trade that creates some of those revenues is something we see as quite unlikely, at least at present." Cunningham said he's concerned that this meth will soon start flooding Europe, and already, doctors at drug rehabilitation centers in Afghanistan say they are seeing more meth addicts now than they saw just a few years ago.

What is causing Afghanistan's food crisis?

Afghanistan has experienced extreme drought conditions for several years, and the damaged crops are producing low yields. Along with the food shortages, many people don't have enough money to buy adequate amounts of food for their families, and those who worked for the previous government and lost their jobs in August are now having to rely on assistance from humanitarian organizations for the first time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The United Nations estimates that 97 percent of Afghans do not have enough food, and half are suffering from acute hunger. The U.N. has asked for $4.4 billion in aid to get food and clean water to those who need it most in Afghanistan.

What is life like for women now in Afghanistan?

Women's rights advocates took to the streets after the Taliban seized power in August, calling on the hardliners not to take away such basic gains as education for girls. Many of these protesters were beaten and detained, and in March, their fears were realized when the Taliban said girls could only attend school up to the sixth grade. This came after the Taliban banned women from going on long-distance road trips in Afghanistan by themselves and prohibited drivers from giving rides to women without veils.

On May 7, the Taliban announced a rule that Muslim women must be covered from head to toe while in public, with a spokesman for the Ministry of Virtue and Prevention of Vice stating this is "not a restriction on women but an order of the Quran." Women who violate this new order will be warned at first, the ministry said, and if they have several infractions, their male relatives will be punished, possibly with prison time.

Why is the Islamic State stepping up attacks in Afghanistan?

The Islamic State affiliate in Afghanistan, known as Islamic State Khorasan or ISIS-K, does not get along with the Taliban; formed in 2015 by disillusioned Pakistani Taliban fighters, ISIS-K does not think the Taliban is strict enough. Over the last several weeks, ISIS-K has claimed responsibility for terrorist attacks that left at least 100 people dead, including the bombings of mosques in northern Afghanistan and a high school in Kabul. Analysts say ISIS-K is working to undermine the Taliban, and by targeting civilians, is instilling fear in the public. However, unlike in Syria and Iraq, ISIS-K does not seem to want territory in Afghanistan.

Asfandyar Mir, a senior expert at the United States Institute of Peace, told The New York Times ISIS-K is hoping other extremist groups will think the Taliban government is weak, and will become allied with the Islamic State. "ISIS-K wants to show its breadth and reach beyond Afghanistan," Mir said, "that its jihad is more violent than that of the Taliban, and that it is a purer organization that doesn't compromise on who is righteous and who isn't."

Are there any divisions in the Taliban?

There does appear to be a division between the Taliban's hardline leader, Hibaitullah Akhunzada, and those who want the government to receive aid from Western nations. The Associated Press reports that some Taliban leaders were angry when Akhunzada decided at the last minute that girls could not go to school after the sixth grade, knowing this move would be denounced by countries who want women's rights to be protected. Still, they are careful not to let the disagreements be made public.

"The leadership does not see eye to eye on a number of matters but they all know that if they don't keep it together, everything might fall apart," former government adviser Torek Farhadi told AP. "In that case, they might start clashes with each other. For that reason, the elders have decided to put up with each other, including when it comes to non-agreeable decisions which are costing them a lot of uproar inside Afghanistan and internationally."

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

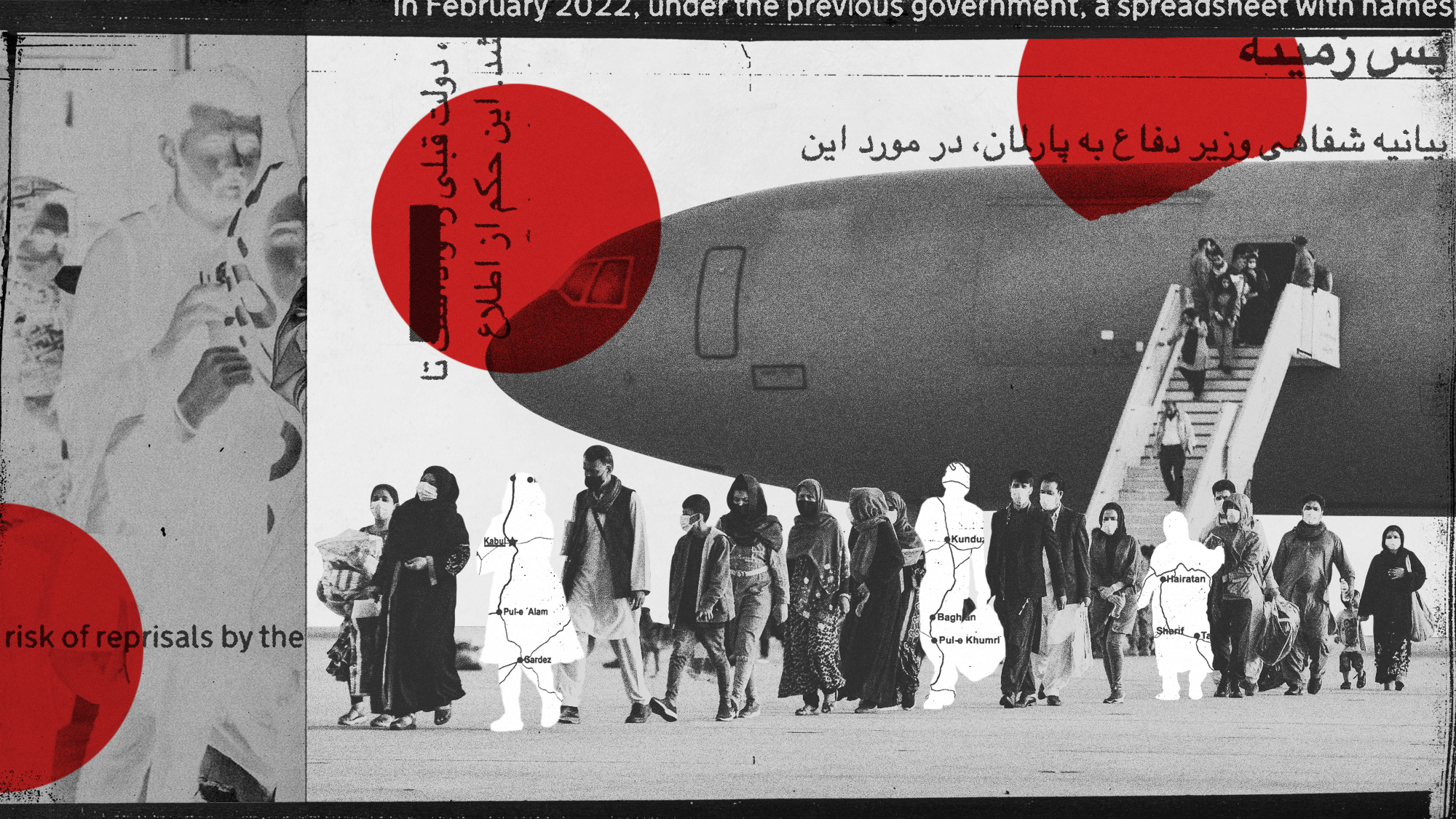

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation scheme

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation schemeThe Explainer Massive data leak a 'national embarrassment' that has ended up costing taxpayer billions

-

Ben Roberts-Smith: will more Afghanistan war crimes trials follow?

Ben Roberts-Smith: will more Afghanistan war crimes trials follow?Today's Big Question Former SAS soldier lost defamation case against Australian newspapers that accused him of murder

-

Did Ukraine orchestrate the Kremlin drone strike?

Did Ukraine orchestrate the Kremlin drone strike?Speed Read If Kyiv isn't behind the humiliating attack, who is?

-

Stealing Ukraine's children

Stealing Ukraine's childrenSpeed Read Vladimir Putin has been charged with war crimes for abducting thousands of Ukrainian children. Why is he doing this?

-

Russia's shadow army

Russia's shadow armySpeed Read The Wagner Group, accused of numerous war crimes, has sent tens of thousands of mercenaries to fight in Ukraine

-

The F-35 fighter jet's troubled history

The F-35 fighter jet's troubled historySpeed Read Why 'the most expensive weapon in human history' still can't get off the ground

-

The U.S. gave Ukraine tanks. Are jets next?

The U.S. gave Ukraine tanks. Are jets next?Speed Read How to balance helping Ukraine without triggering a wider war with Russia

-

Can the UK rely on the British Army to defend itself?

Can the UK rely on the British Army to defend itself?Today's Big Question Armed forces in ‘dire state’ and no longer regarded as top-level fighting force, US general warns