Stealing Ukraine's children

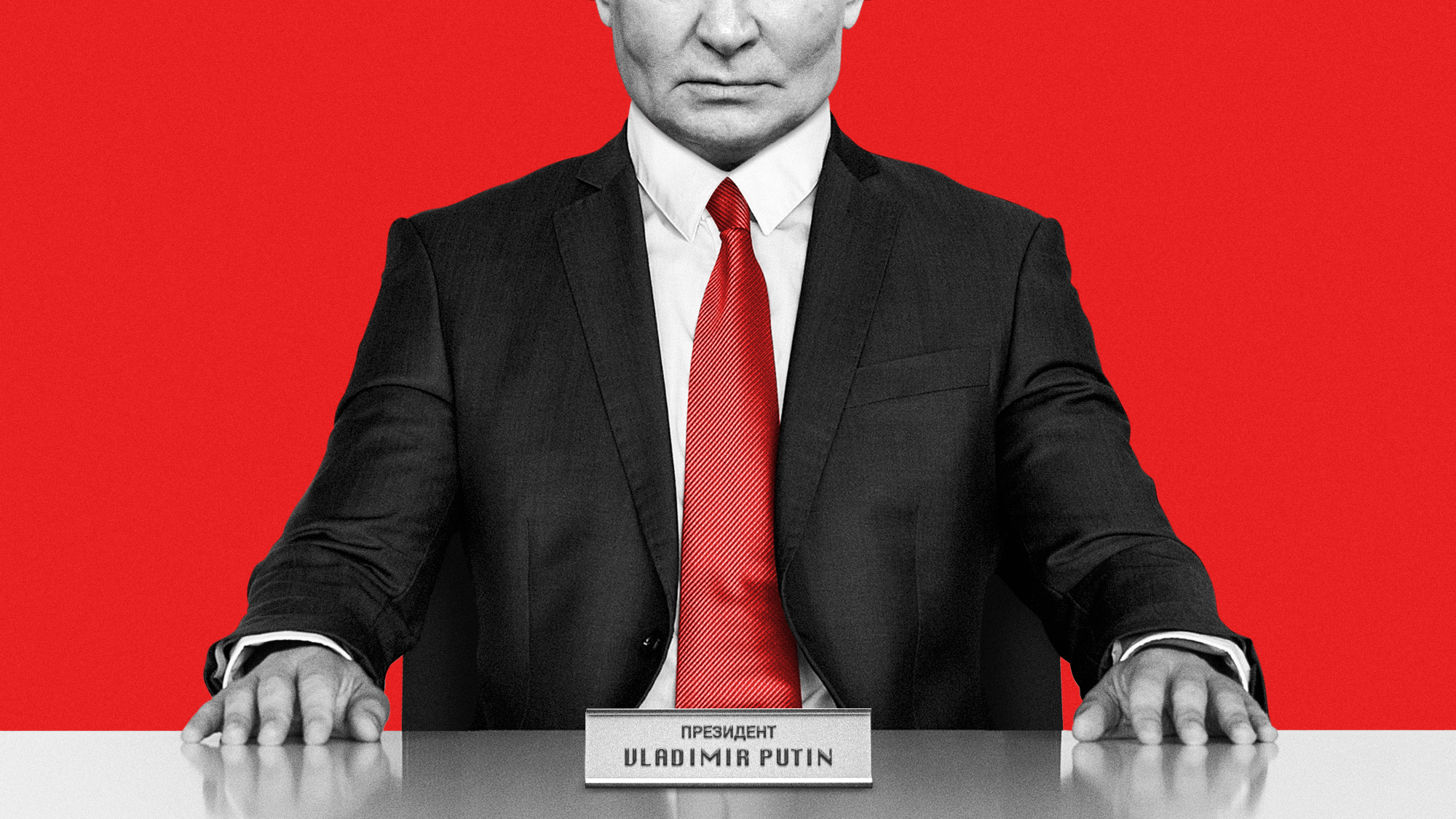

Vladimir Putin has been charged with war crimes for abducting thousands of Ukrainian children. Why is he doing this?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Vladimir Putin has been charged with war crimes for abducting thousands of Ukrainian children. Why is he doing this? Here's everything you need to know:

What are the charges?

The International Criminal Court recently accused Putin and his top children's rights envoy with unlawfully seizing and moving thousands of children out of their home country. That's a violation of multiple U.N. human rights conventions. Of the thousands of war crimes linked to the Russian president, this is one of the easiest to substantiate. Ukrainian children ranging from infants to 17-year-olds are known to have been deported to Russia or Russian-occupied territory, most of them without their parents. Human rights officials and Ukraine's government say the number of minors taken is at least 16,000 and may be as high as 400,000. Russian propaganda portrays the abductions as humanitarian "evacuations" to get children out of harm's way in besieged Ukraine. But Ukraine and human rights organizations say the children have suffered physical and sexual abuse, the severing of family ties, and indoctrination in pro-Russia "re-education" camps. "They change their citizenship, give them up for adoption under guardianship, commit sexual violence, and other crimes," said Ukraine's Children's Rights Commissioner Daria Herasymchuk. "It's an act of genocide."

How do the kidnappings take place?

Russian forces have used a variety of tactics. As far back as 2014, Russian-backed separatists in Luhansk stopped groups of dozens of children at checkpoints, took them away from parents and adults, and funneled them across the border. During the war, children have been separated from their parents through phony "evacuation orders" and in filtration camps. Russian troops have also scooped up children from schools, hospitals, and orphanages. Orphanages in pre-war Ukraine held more than 105,000 children — more than in any other European country except Russia — but 90 percent of those children had living relatives. In some cases, Russian-backed puppet governments in occupied territories took over the orphanages and arranged for the rapid transfer of children into Russia.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What happens to them?

Some are swiftly put up for adoption, with Russia offering its citizens between $300 and $2,000 in state aid per child. The government has staged photo-ops in which dazed children are welcomed with teddy bears, gift baskets, and hugs from strangers. Under a decree signed by Putin last May, they're then fast-tracked for Russian citizenship. At least 6,000 children have landed in at least 43 re-education camps. Desperate to get their children away from the shelling, some Ukrainian parents in occupied territory agreed to send them away for short stays at what were depicted as rehabilitative summer camps, only to have the children held hostage. They have been shuttled to camps as far away as the Pacific coast — closer to Alaska than Ukraine.

What's known about the camps?

Their purpose is to erase all remnants of the children's Ukrainian identity and turn them into patriotic Russians. Inessa Vertash of Beryslav in occupied Kherson Oblast reluctantly let her 15-year-old son, Vitaliy, attend a Russian camp at the urging of his school's headmistress. After two relatively pleasant weeks, he was moved to another camp that, he said in a rare phone call home, was "like a prison." Attendees were beaten for refusing to sing the Russian national anthem, sexually abused, and psychologically manipulated. "They told the children: Your parents have left Ukraine and are never coming for you," Vertash said.

What is Russia's goal?

Ethnic cleansing. Putin wrote an infamous essay in July 2021 arguing that Ukrainian nationhood was a 20th-century fabrication, and that Ukrainians and Russians are "one people" — all of whom are Russian, whether they admit it or not. He later used this ideology to justify the invasion and attempted takeover of Ukraine. The kidnappings appear to be an attempt to replenish a dwindling Russian population, depleted by a low birth rate, aging, extensive emigration, and the carnage of the war. This meets the U.N.'s 1948 definition of genocide, which in addition to mass killings includes "forcibly transferring children of the group to another group" and "deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part."

Can the children be saved?

About 320 have been returned so far, and the Ukrainian government has asked foreign governments and international organizations for help in retrieving more. But Putin last month said he plans to expand, not abandon, the "Happy Childhood" program in coming months, and Russia makes it as difficult as possible for parents to recover their children. In some cases, it has barred anyone but a child's legal parent from picking up a child in Russia. Since Ukraine currently bars adult men under 60 from leaving the country, that often means only the mother can make the dangerous, prohibitively expensive journey into Russia via a third country to pick up her children. Olga Lopatkina managed to recover six of her nine children from occupied Donetsk after months of effort and negotiations. The children had been told to forget her. "Doesn't Russia have its own kids?" she said. "I have no idea why they need ours. I guess it's just to hurt us."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Putin's cuddly child-snatcher

In addition to Putin, the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia's commissioner for children's rights. The 38-year-old wife of a Russian Orthodox priest, Lvova-Belova has proved adept at putting a sweet, motherly face to the government's policy of abduction. She claims to have hugged more than a thousand children and has personally accompanied "evacuations" of youngsters from occupied Ukraine, which often end in well-publicized handovers to adoptive families. Russians, she has said, are uniquely equipped to provide "shelter" and "warm them with care and love." In addition to Lvova-Belova's five biological children, her family includes 18 adoptees. One of them, 15-year-old Filip, was brought over from Mariupol last spring. "I realized that I couldn't live without this child," she said. At first the teen was vocally pro-Ukrainian. But by the time he became a Russian citizen last September, Lvova-Belova claims, he'd learned to be thankful for "his great Russian family."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?Today's Big Question Security agreement commits British and French forces in event of ceasefire

-

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?Today’s Big Question ‘Mildness’ of EU pushback against Trump provocation ‘illustrates the bind Europe finds itself in’

-

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?Today's Big Question How best to boost troop numbers to deal with Russian threat is ‘prompting fierce and soul-searching debates’

-

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?Today’s Big Question ‘Unpalatable’ US plan may strengthen embattled Ukrainian president at home

-

The Baltic ‘bog belt’ plan to protect Europe from Russia

The Baltic ‘bog belt’ plan to protect Europe from RussiaUnder the Radar Reviving lost wetland on Nato’s eastern flank would fuse ‘two European priorities that increasingly compete for attention and funding: defence and climate’

-

How should Nato respond to Putin’s incursions?

How should Nato respond to Putin’s incursions?Today’s big question Russia has breached Nato airspace regularly this month, and nations are primed to respond

-

What will bring Vladimir Putin to the negotiating table?

What will bring Vladimir Putin to the negotiating table?Today’s Big Question With diplomatic efforts stalling, the US and EU turn again to sanctions as Russian drone strikes on Poland risk dramatically escalating conflict

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war