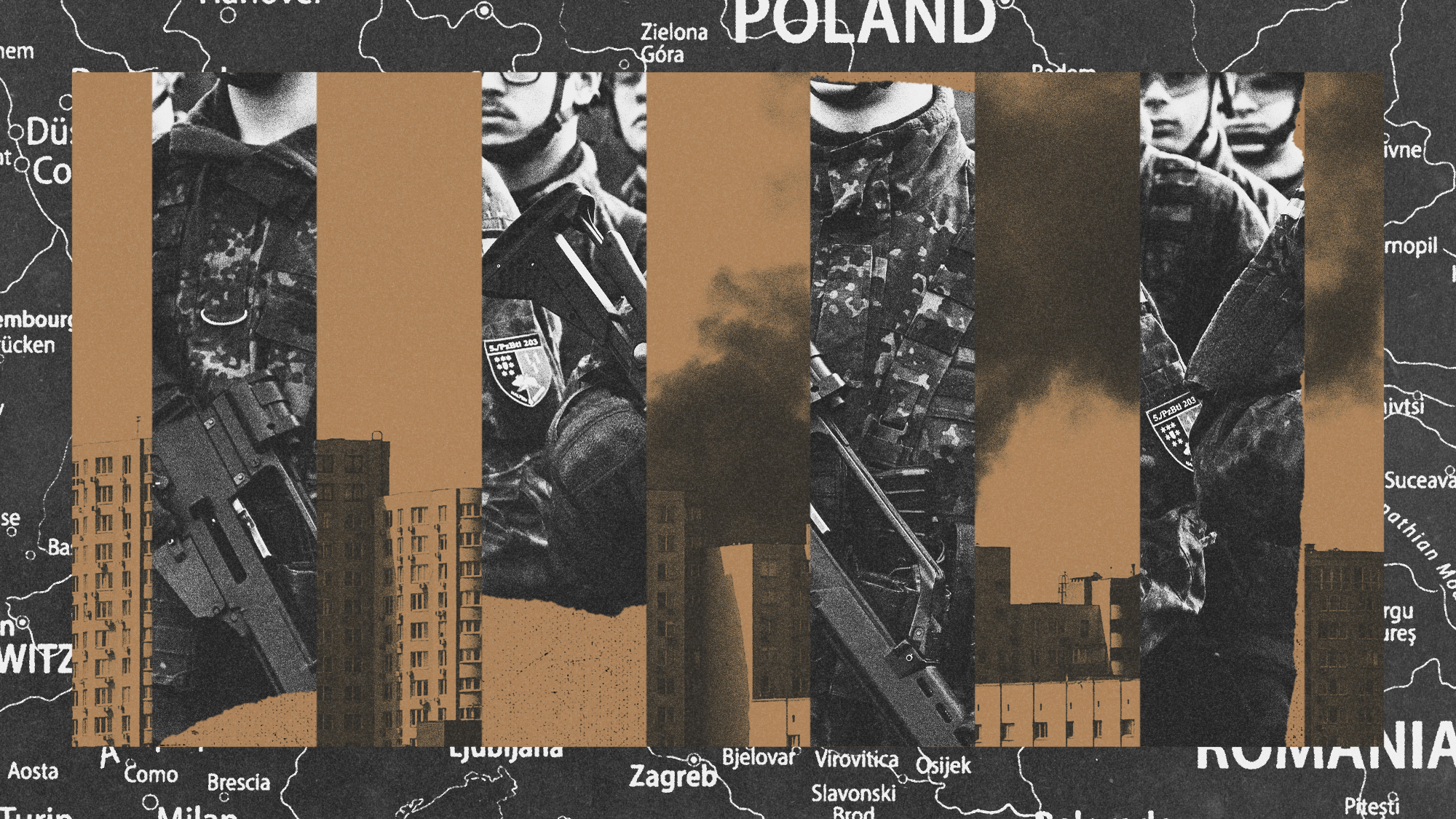

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?

How best to boost troop numbers to deal with Russian threat is ‘prompting fierce and soul-searching debates’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Emmanuel Macron has said a new voluntary national service programme in France, announced today, is not about “sending our youth to Ukraine” to fight.

The growing realisation that Russian aggression could “easily spill into Europe” has put “intense pressure” on countries across the continent to “quickly expand the ranks of full-time soldiers and reservists that shrank during the post-Cold War peace”, said The New York Times.

“Yet the question of how to recruit hundreds of thousands of service members is prompting fierce and soul-searching debates.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the commentators say?

France’s new national service plan “stops short” of full conscription, said France 24. Lasting 10 months, with volunteers paid for their service, it is “expected to start modestly”, recruiting 2,000 to 3,000 people in the first year, before “ramping up” with a long-term goal of 50,000 per year.

“Some countries in Europe already have a form of a conscription”, said The Times, notably those “closest to Russian borders” such as Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania. But the war in Ukraine, and the so-called “grey zone” activities carried out by the Kremlin such as drone incursions into Nato airspace, “have reignited the debate across the continent”.

In Poland, “plans are under way for every man to go through military training”, said The New York Times, as the government aims to more than double the size of its army to 500,000. In the hope of also growing its fighting force from 70,000 to 200,000 by 2030, Denmark recently expanded its military conscription programme to include women turning 18 who are entered into a conscription lottery. Croatia has gone further, voting in October to reintroduce compulsory military service, which was suspended in 2008.

Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, this month opted for a “new military service” made up initially of a volunteer force that mirrors a system used in Sweden, where a questionnaire is sent out to all 18-year-olds. Conscription, which ended in 2011, “is not compulsory under the new rules but this model does include the potential for that”, said DW.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It marks the “first unmistakable shift in German security policy for a generation”, said Henry Donovan in The Spectator. Far from being an “overreaction” as some claim, “it is the minimum a serious country does when confronted with the concrete possibility of war on its own continent”.

Britain should also “pay close attention”. Up to now the UK government has ruled out reintroducing conscription (which was abolished in 1960) to boost its number of military personnel, instead favouring a recruitment drive by the Ministry of Defence.

What next?

Security and defence analysts, as well as Nato Secretary General Mark Rutte and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, have warned that Russia could be ready to expand its war into Europe within the next five years.

Even with countries vowing to “do a better job of attracting volunteers to fulfil national targets and commitments to Nato”, the “outlook for meeting targets is dim”, said The New York Times. “Retention rates remain low in many countries, reserve schemes are uneven and recruitment has dwindled in ageing societies with low unemployment,” the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a European think tank, concluded in a recent report.

The problem is that less than a third of EU citizens appear willing to fight for their country in a war, according to a 2024 poll by Gallup.

“Even if conscription would help address issues with military recruitment, in many countries it could be socially and politically controversial to the point that it reinforces polarisation, leads to backlash or social/political unrest, and undermines the wider security benefits that could be gained from it,” Linda Slapakova, from research institute RAND Europe, told Euronews.

This view was summed up by France’s chief of the defence staff, General Fabien Mandon, last week. While France has the economic and demographic power to defeat Moscow, it lacked the “spirit” in society to stand up to the threat, he said. “If our country falters because it is not prepared to accept – let’s be honest – to lose its children, to suffer economically because defence production will take precedence, then we are at risk.”

Elliott Goat is a freelance writer at The Week Digital. A winner of The Independent's Wyn Harness Award, he has been a journalist for over a decade with a focus on human rights, disinformation and elections. He is co-founder and director of Brussels-based investigative NGO Unhack Democracy, which works to support electoral integrity across Europe. A Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellow focusing on unions and the Future of Work, Elliott is a founding member of the RSA's Good Work Guild and a contributor to the International State Crime Initiative, an interdisciplinary forum for research, reportage and training on state violence and corruption.