America isn't special because it apologizes

Politicians know that Americans want to feel exceptional

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America is exceptional in many ways. Apologizing for our sins is not one of them.

In the past week or so, how many times have you heard someone say that what makes America unique among other nations is that even though we are capable of heinous mistakes, we alone have the moral insight to recognize them, to provide an accounting of them, and to change because of them?

The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence's report on the CIA's torture program is an "act of self-examination" that "keeps us a model that others want to emulate, partner with, and immigrate to," writes Thomas Friedman. If our official sins are "not exposed and checked, such actions could damage our society as much as a terrorist attack."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

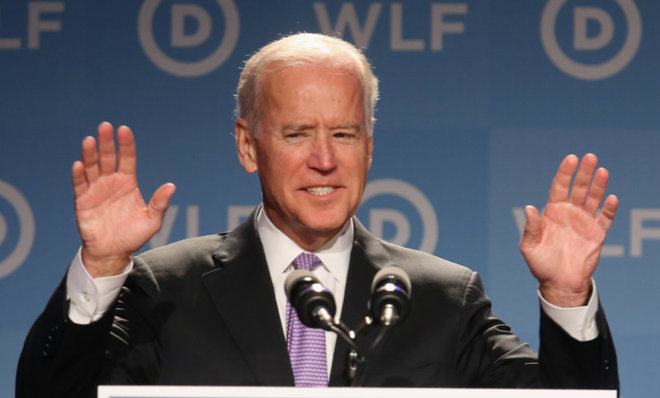

Vice President Joe Biden was more effusive: "Think about it. Name me another country that's prepared to stand and say, 'This was a mistake. We should not have done what we've done, and we will not do it again.'"

Sounds comforting. American self-righteousness soothes the burns from blowback. School kids learn that we mistreated Indians and gave them land to atone. They learn that we interned Japanese-Americans and gave them money. They learn that we rebuilt Europe after World War II.

America does absorb and process an unusually large number of its own failures. But we are not unique.

Germany had to exorcize so many demons after Hitler that even free speech is somewhat curtailed.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission after apartheid was flawed and yet still monumental.

The British are as capable as we are of documenting and then correcting abuses. So are the Australians.

Even Khrushchev denounced Stalin.

In some ways, despite the heroic efforts of theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr to recognize in our civic culture a strain of self-recrimination that leads to moral progress, we are not as exceptional as Germany. We recognize that our country was built by slave labor and haven't really figured out how to atone for it.

Better to see, as Peter Beinart does at The Atlantic, that American government perhaps uniquely recognizes how flawed we are as human beings and has found, over time, an efficient and procedurally fair way to ensure that our worst instincts are checked.

There's an acute tension between the intellectual class and the political class about torture. Politicians and intellectuals know that torture is wrong. Intellectuals want accountability in the form of legal redress. The politicians, bearing responsibility for instigating the policies in the first place, want to move on in the easiest way possible.

Public opinion always influences what happens next, and here, the intellectuals are behind the politicians. Politicians know that Americans want to feel special, so they tell us that the way we hold ourselves accountable for our mistakes is some immutable, collective characteristic that we all share.

Usually, atonement includes sacrifice. Practically, our political leaders know that they cannot spread the costs of actual atonement around, because that would be too much to bear. They settle instead for a historical accounting. Is this morally monstrous? Not when politicians are held accountable by voters. Voters will punish politicians who punish them, who drag the country into places that seem too uncomfortable and out of synch with progress.

When Edward Snowden exposed the National Security Agency's surveillance program, the public was quickly outraged, then not, then Congress tinkered with some reforms, then it mostly lost momentum, and then a few journalism prizes were won. Now, while the debate about privacy and surveillance is certainly louder than it was, it is not at all edifying.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

Why Puerto Rico is starving

Why Puerto Rico is starvingThe Explainer Thanks to poor policy design, congressional dithering, and a hostile White House, hundreds of thousands of the most vulnerable Puerto Ricans are about to go hungry

-

Why on Earth does the Olympics still refer to hundreds of athletes as 'ladies'?

Why on Earth does the Olympics still refer to hundreds of athletes as 'ladies'?The Explainer Stop it. Just stop.

-

How to ride out the apocalypse in a big city

How to ride out the apocalypse in a big cityThe Explainer So you live in a city and don't want to die a fiery death ...

-

Puerto Rico, lost in limbo

Puerto Rico, lost in limboThe Explainer Puerto Ricans are Americans, but have a vague legal status that will impair the island's recovery

-

American barbarism

American barbarismThe Explainer What the Las Vegas massacre reveals about the veneer of our civilization

-

Welfare's customer service problem

Welfare's customer service problemThe Explainer Its intentionally mean bureaucracy is crushing poor Americans

-

Nothing about 'blood and soil' is American

Nothing about 'blood and soil' is AmericanThe Explainer Here's what the vile neo-Nazi slogan really means

-

Don't let cell phones ruin America's national parks

Don't let cell phones ruin America's national parksThe Explainer As John Muir wrote, "Only by going alone in silence ... can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness"