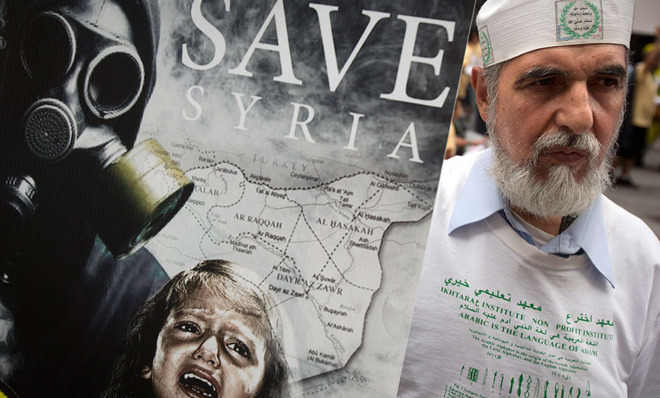

How Western companies sneakily sold chemical weapons components to Syria and Iraq

Bad actors can run rings around non-proliferation laws via "dual-use" chemicals

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Outgoing Foreign Secretary William Hague admitted this week that in the 1980s British companies sold precursor chemicals to the Syrian government that Damascus used to manufacture lethal sarin.

But even as late as 2012, British firms were planning to honor contracts to export dual-use chemicals to Syria — in other words, chemicals that could have civilian or military applications. Pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and medicines all contain agents that could also be weapons.

German and Indian firms also have legally sold dual-use chemicals to Syria in recent years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Dual-use chemical complicate governments' efforts to limit the spread of chemical weapons. In the early 1990s, the U.S. tried to block the shipping of dual-use products to Iran, Libya, and Syria. Washington had to deal with multiple Southeast Asian firms and Middle Eastern port authorities.

Companies successfully argued that U.S. dual-use standards did not apply to them since they weren't American firms. Some told Washington that it had no case unless it could prove the companies' clients were misusing the materials.

While control mechanisms have improved since the formation of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, the OPCW doesn't have absolute jurisdiction over dual-use products.

In 1991, a U.N. dossier outlined years of dual-use sales to Iraq worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Fortunately for the firms involved, the U.N. couldn't positively link these sales to Iraq's work on VX nerve gas.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The U.S. and the U.K. both previously had sold hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of dual-use equipment to Iraq in the early 1980s. But for Baghdad, the foreign suppliers that really counted were German.

By purchasing materials in small amounts through a clandestine global procurement network, Iraq ran rings around non-proliferation laws. West Germany tightened up it chemical export controls in 1984, but the damage was done. In 1992, the U.N. cataloged products from 17 different German companies at Iraq's Al Muthanna chemical-weapons complex.

Aside from Iraq, German suppliers were also active in Libya and Syria. Saddam Hussein, Hafez Al Assad, and Moammar Gadhafi were happy to oblige corporate and military interests in both Germanies. West German corporations mostly dealt in goods and high technology. The East German army supplied training and blueprints.

Firms in the U.S., France, India, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, Malaysia, Italy, Singapore, the USSR, Japan, China, North Korea, the two Germanies, Thailand, The Netherlands, Austria, and the U.K. all were involved in dual-use sales to Iraq, Libya, or Syria. After U.N. inspectors got access to Iraqi records following the 1991 Gulf War, the U.N. didn't publicize who had sold what … in order to avoid embarrassing leading governments.

Syria established its chemical program with Soviet military assistance as a deterrent to Israel. Like Iraq, Syria turned to British and German companies in the 1980s and 1990s. As Western sanctions tightened, Syria sought products from Iran, India, North Korea, and Russia.

In 2013, Syrian president Bashar Al Assad cut a deal to have the OPCW remove his chemical infrastructure. Syria's program depends on imports, so the OPCW has its work cut out for it to ensure Syrian compliance. All Damascus has to do to rebuild its chemical stockpiles is find a seller and some smugglers.

The small Libyan program never attained self-sufficiency nor high production totals. But it did involve one well-documented episode that illustrates just how far some suppliers would go for their dictatorial clients.

Starting in 1984, Imhausen-Chemie worked through Libyan officials' shell corporations to circumvent export controls. The West Germany company even constructed a fake factory in Hong Kong to complete the charade.

Imhausen-Chemie's suppliers including Siemens, Toshiba, and ITT all believed they were selling their wares to a legitimate Hong Kong-based operation. Instead, their goods ended up at secret factories in Libya.

German authorities shut down Imhausen-Chemie's operation in 1990. But Libya continued to produce small amounts of chemical weapons until 2003, when the country willingly surrendered its stockpile.

The full extent of corporate cooperation with these regimes may never be known. The last time a member of the German parliament proposed a fact-finding commission, everyone but the Green Party reps voted against it.

From drones to AKs, high technology to low politics, War is Boring explores how and why we fight above, on, and below an angry world. Sign up for its daily email update here or subscribe to its RSS Feed here.

More from War is Boring...

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown