For millions of part-time workers, the jobs crisis isn't over

The underemployment rate remains abnormally high, a reflection of continuing weakness in the labor market

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

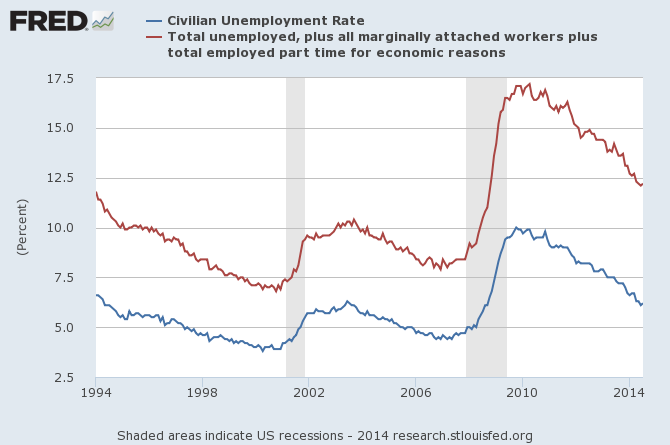

All things considered, the U.S. has done a decent job of addressing the jobs crisis of the last few years. The jobless rate in the U.S. is just 6.2 percent, well below the double-digit peak it reached in 2009. In the eurozone, by contrast, the unemployment rate is 12 percent — and it isn't coming down, the result of a succession of policy mistakes that have facilitated an epic economic depression.

But while the U.S. has used fiscal and monetary stimulus to bring down the headline unemployment rate, there are still a whopping 7.5 million people working part-time who want full-time jobs. And for the sake of the economic recovery, the U.S. government must do more to help these part-time workers.

The headline unemployment rate — U-3 in the jargon of the Labor Department, shown in blue in the graph below — merely measures those who are looking for work. A more complete accounting of workers without full-time jobs — U-6, also known as the underemployment rate, shown in red — includes part-time workers seeking full-time work and those who have dropped out of the labor force altogether.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

U-6 is coming down fast, but it still hasn't fallen to its pre-recession levels. Indeed, the high underemployment rate suggest the labor market is still far from a full recovery. As Jeanna Smialek and Jeff Kearns of Bloomberg note:

About 28 percent of all part-time workers in July reported that slack business conditions or a dearth of full-time jobs kept them from finding full-time work. That's up from a 19 percent share at the start of the downturn. [Bloomberg]

That is a problem for a lot of people — and the broader economy. A part-time job obviously doesn't pay what a full-time job does or provide benefits. That makes it harder to invest for retirement, to amass money to start a business, to put a down payment on a house, to save for your children's college costs, and to afford a decent standard of living.

The problem is that Congress is incapable of doing anything about it. Fiscal policy is out of the question because of the paralysis and deficit phobia in Washington. Both sides say they want to help the economy, but can't agree on the best approach. Republicans favor tax cuts, and Democrats favor spending, but neither side is keen to increase the deficit even in the name of creating jobs and boosting the economy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That leaves monetary policy. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen says she is concerned about the problem of part-time employment. And the central bank's charter does call for maximum employment, as well as stable prices.

Unfortunately, the Fed uses U-3 to define maximum employment. The Fed sees maximum employment as a U-3 level between 5.2 percent and 5.5 percent. And as the economy is gradually approaching that level, the Fed has begun tapering its quantitative easing stimulus program and talking about raising interest rates.

But there is no good reason to leave the underemployed out in the cold. Fortunately, Yellen appears to agree. In March, she noted that many Americans "lost a full-time job in the recession and seem stuck working part time." She also argued before Congress in July that the recovery is unfinished, and that there remains "significant slack" in labor markets.

This is hopefully a sign that she is determined to keep interest rates low to assist the underemployed, and to give the economy a longer opportunity to heal.

Other members of the Fed's board, such as Richard Fisher and Charles Plosser, are less sympathetic to continued monetary stimulus, citing inflation fears. But inflation remains low and contained, right on the Fed's 2 percent target. That means the Fed can continue to keep rates low, which is exactly what it should do.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal