Europe is in an epic depression — and it's getting worse

Why is the European Central Bank ignoring its mandate?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Economic growth in Europe came in at zero in the second quarter of 2014. That's better than being in recession. But it's not the growth that Europe — with its huge unemployment rate of 12 percent, or roughly 19,130,000 people out of work — needs.

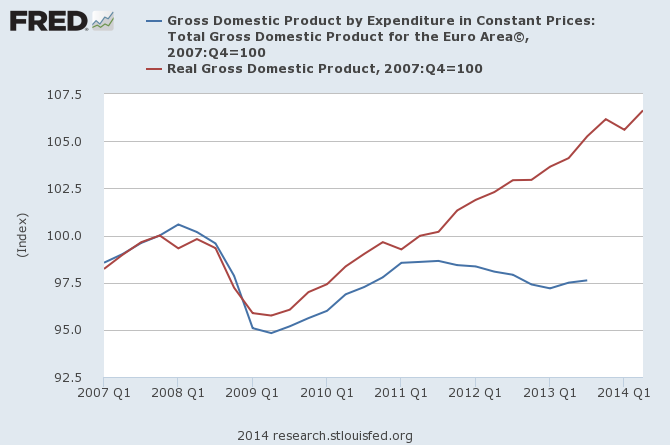

The euro zone (below in blue) has been in a depression since the financial crisis. That's because in terms of gross domestic product, the euro zone has not risen back to its pre-financial-crisis levels. The U.S. (below in red), on the other hand, has gotten out of its slump and continues to grow at a decent clip:

(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis/OECD)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With industrial production stagnant, mass unemployment still a problem, and inflation on a downward trend, economists such as The New York Times's Paul Krugman worry that Europe is turning into Japan. The former second-largest economy in the world has spent more than 20 years in a deflationary depression, a spiral of falling prices which encourage people to sit on cash, causing prices to plunge even further. Europe — with its aging population — has similar demographics to Japan, too, worsening the likelihood that it might end up in the same trap.

That might be bad, but it's still a lot better than total collapse — which is what was widely feared in 2011 and 2012 when government interest rates rose drastically in countries like Italy, Spain, Greece, Ireland, and Portugal over fears about the sustainability of their sovereign debts. Under the euro, countries don't control their currencies, so they run a real risk of running out of money. The architects of the euro system, such as Romano Prodi, knew that this would be a problem but decided that they would cross that bridge when they came to it.

Since then, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) have been able to deploy various tools, including so-called outright monetary transactions, to backstop those governments and contain the sovereign debt crisis. Interest rates — even for countries like Spain, which two or three years ago looked in serious danger of default — are now as low as they are in the United States. Perhaps this episode illustrates that the euro was an incompetently designed currency, but the cleanup at least has been a major victory for the ECB.

But by this point it should be pretty clear that simply containing the sovereign debt crisis isn't enough. The Federal Reserve under Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen is proof that central banks can do much more to avert an economic depression and ensure a recovery. Central banks have tools like quantitative easing to fight unemployment and raise growth.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Alas, the ECB has not really shown interest in using such tools. Opposition to quantitative easing among euro member states — particularly Germany — remains high. And although the ECB's governor, Mario Draghi, has promised that the ECB can theoretically do more, he believes that — even in spite of the low-growth, low-inflation, high-unemployment environment — the European recovery remains "on track" and is more worried about crises in the Middle East and Ukraine than the millions of unemployed people in Europe itself.

Of course, the ECB — unlike the Fed — is not required to achieve low unemployment. It has a single mandate for price stability, which it defines as 2 percent inflation per year.

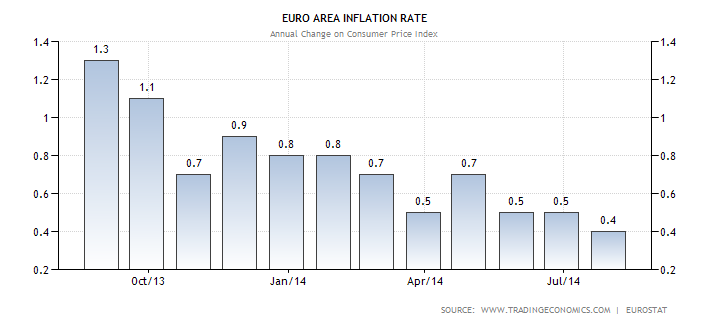

But let's be real here — even though the ECB has set interest rates extremely low by historical standards (interest rates on bank deposits are currently at a record low -0.1 percent, the ECB hasn't been meeting its 2 percent per year mandate. Inflation in the euro zone currently stands at just 0.4 percent:

(Eurostat)

So this isn't a matter of the ECB's not having a mandate for low unemployment or the euro system's being badly constructed. Although critics of the ECB and the euro system, such as Pieria View's Frances Coppola, are right in their criticisms, this is a far simpler matter. The ECB is failing to meet its inflation mandate. Things are bad and getting worse, and Draghi is in denial.

When push came to shove, the ECB backstopped the eurozone nations like Spain and Italy. So it's possible that the ECB could finally engage in quantitative easing when inflation falls below zero. But that will be too late to help the millions of unemployed that the ECB has left out in the cold. It will be too late to avert an economic depression. And it may be far too late to prevent the euro zone from falling into a prolonged Japanese-style trap.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.