The most dangerous result of the CIA torture scandal

Thanks, CIA

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Vladimir Pozner, whom you might remember as a perspicuous commentator on the Soviet Union during the Sochi Olympics, was famous in America in the 1980s for being an articulate defender of the U.S.S.R. He was able to argue his points in the American style of competitive political debate, which is to say: he knew how to talk in sound bites that resonated.

Posner is very smart, and he used one technique over and over, particularly when confronted with a particular horror that the Soviet Union was accused of. He would invariably respond that Americans have no moral authority to judge the Soviet Union because, well, whatever the misdeed in question, the U.S. did it too.

Soviet authoritarianism? Well, the U.S. never criticizes China, which has a much worse record, and always focuses on the Soviets. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan? Not any different than America's subjugation of Vietnam. Political prisoners? America's prison system is no model for the world. Civil rights? What about the horror of America's inner cities?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Tu Quoque is the word rhetoricians apply to this kind of argument. It is a fallacy, of course; simply because both sides might do something or engage in a behavior that draws analogies does not mean that the criticism itself is invalid. But we fall for this all the time. It's a staple of political discourse. To Quoque arguments are a subtle variant of the ad hominem fallacy; they undermine the moral authority of the person making the critique by associating him or her with the very behavior that he is condemning.

Those tortured by the Central Intelligence Agency were most harmed by the torture. Obviously. Our sense of superiority, of humanism, of being special in the world, has also been degraded by the knowledge that people were tortured in the name of protecting us. But the most dangerous consequence of the CIA's torture escapades is the gift they have given to countries that are either inclined to treat their citizens the same way or have been casting about for a way to justify to an internal political audience that American initiatives that might actually be freeing, liberating and worthwhile are not worth pursuing. Because, you know, America did it too.

The real harm is not that the scandal gives people a good excuse to make life difficult for Americans, it's that it gives them a bad excuse that is so much more emotionally powerful.

A country doesn't cooperate with war crimes tribunals? Well, America never brought to trial the people who tortured its detainees.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A country uses American money to detain and harass people on the basis of politics. Well, America threw innocents into a black hole prison and tortured people.

Good countries with good motives, or mixed motives, will incorporate the fact the American tortured prisoners into the larger scheme of foreign relations. Less friendly actors will seize on anything to get out of doing what's right.

Thanks for that, CIA.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon

-

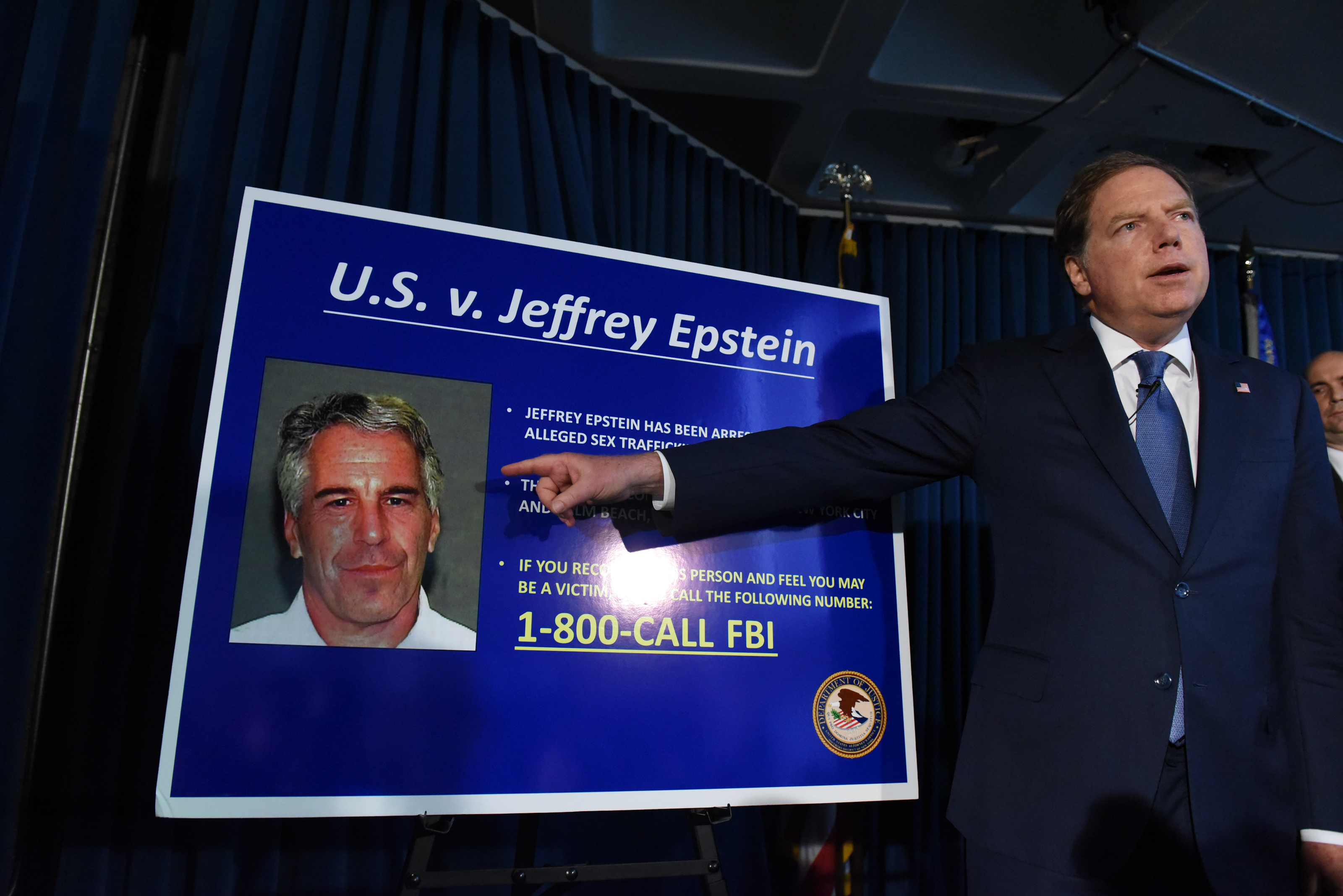

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootingsThe Explainer Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of LoveThe Explainer Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound