Outing the CIA's station chief in Kabul was a blunder, not a crime

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The serving chief of station for the CIA's massive Kabul base was outed this weekend, and ceremoniously so. As you've probably read by now, a White House press liaison traveling with President Obama on his secret trip to Afghanistan sent the designated pool reporter, Scott Wilson, a list of American officials Obama would be meeting with during the visit.

The list included the name of the CIA's chief of station, a serving undercover intelligence officer, along with his title, "Chief of Station."

It is not a felony to disclose the name of a serving CIA officer. It is a felony to knowingly and without authorization disclose the name of a serving CIA case officer. After muckraking journalists and internal critics began to publish the names of case officers in the turbulent 1970s, the CIA convinced Congress to write a new law officially imposing criminal penalties, in the words of the Congressional Research Service,

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

for the intentional, unauthorized disclosure of information identifying a covert agent with knowledge that the information identifies a covert agent as such and that the United States is taking affirmative measures to conceal the covert agent's foreign intelligence relationship to the United States. Covert agents include officers and employees of a U.S. intelligence agency

Predictably, as soon as this blunder was uncovered, critics of the White House's secrecy policies began to wonder aloud who would get prosecuted for the leak, comparing it to the Bush-era outing of serving CIA officer Valerie Plame, the cover-up around which led to an expensive special investigation and a conviction against Vice President Cheney's then chief-of-staff for misleading investigators. The ramifications of the Plame leak seem to have been fairly grave for a number of vital ongoing intelligence operations.

The ramifications here, at least from the outset, are not as bad. Station chiefs of major CIA stations are generally known, at least by name, often by sight, to rival intelligence agencies almost from the get-go. Certainly, the station chief, in working with a number of different agencies in Afghanistan, would have to accept that his degree of freedom to control his cover is probably tiny at this point. When the CIA appoints chiefs of stations, the agency generally understands and accepts the risk that the identity, and perhaps the person's cover history, might be exposed. Occasionally, this can lead to compromised operations, although generally, enough time has elapsed between these officers having actively run agents and operations (as opposed to having managed them) that the risk is — again, to the use the word — acceptable. The more dangerous consequence is not so much that rival spooks figure out the name of the CIA's man or woman in a certain country. It's that the country or targeted entity can use this information to pin a target on the person's back, which is exactly what elements of the Pakistani government did during a dispute about drones and intelligence-sharing a few years back.

There may well be a criminal reference to the Justice Department here by the White House, just to avoid the impression that they treat classified information disclosures cavalierly or have different standards for their own flock. Unfortunately, the chain of events does not make it likely that anyone would ever be brought to trial. It appears that the U.S. military just copied and pasted a list of meeting attendees that itself should have been formally classified (because it included the identity of a classified agent) but was not, because of the haste of the trip, and someone in the White House press office simply didn't read the list with an eye for that very obvious land mine. The disclosure, practically, was "authorized."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Embarrassing? Yes. Worthy of an investigation? Yes. A chance for critics of the White House to gloat? Yes. A crime? No.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

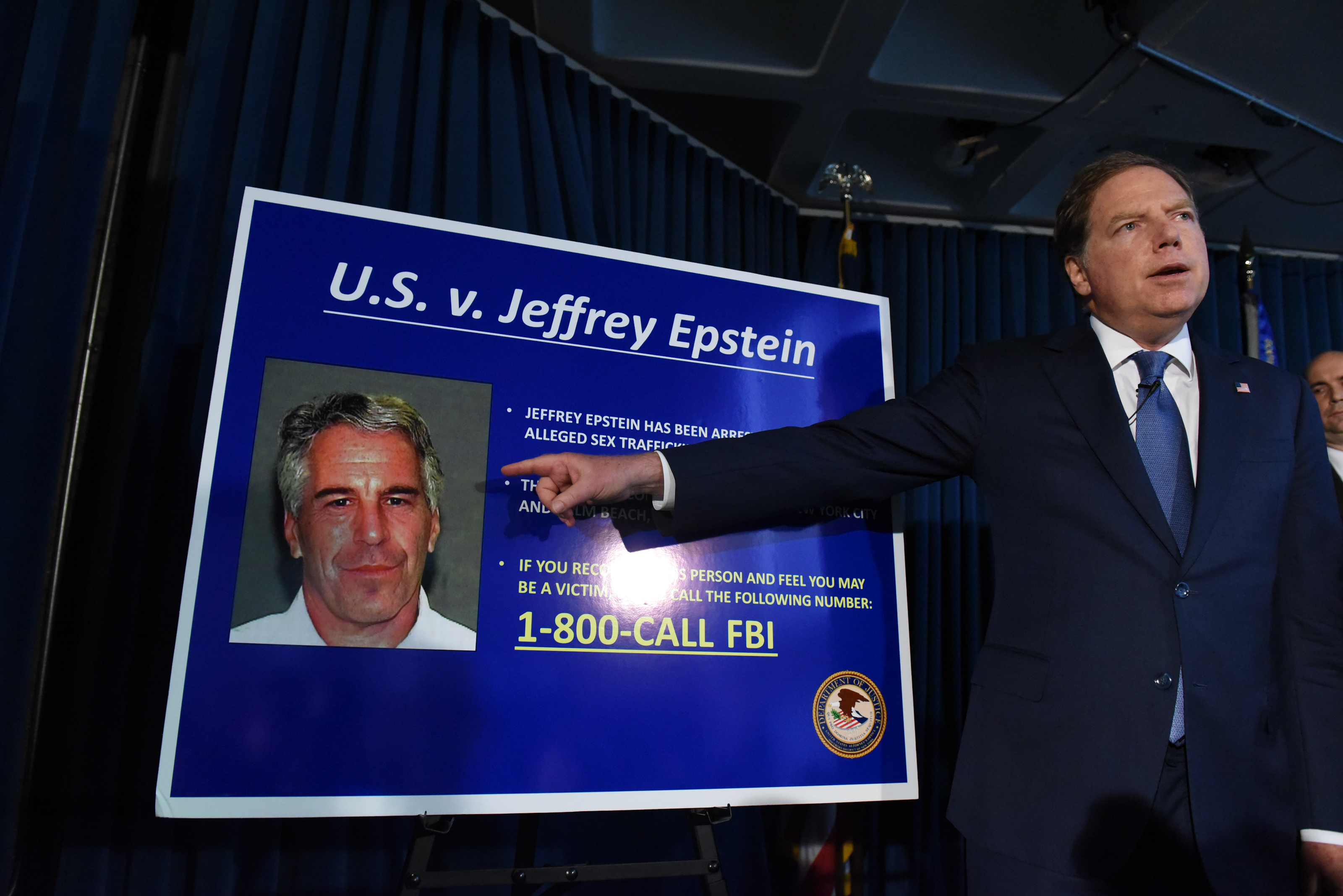

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootingsThe Explainer Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of LoveThe Explainer Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound