How Shonda Rhimes can become TV's most important creative mind

Ignore the luridness of Grey's Anatomy and Scandal and you'll find something truly groundbreaking

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Grey's Anatomy didn't seem like a series that would change television. When it premiered in 2005, ER was already well into its 11th season, and audiences had seen countless riffs on the medical drama, from General Hospital to St. Elsewhere to Chicago Hope. Showrunner Shonda Rhimes was a relative newcomer to the biz, with only one television credit to her name and two girl-centric films: the Britney Spears vehicle Crossroads and The Princess Diaries 2.

But this sleepy midseason replacement unexpectedly took TV by storm — and by its second season, Grey's Anatomy was one of ABC's biggest hits. Within two years, Rhimes leveraged its success into the spin-off Private Practice. In 2012, she launched her next major hit, Scandal. Now she's in the process of prepping number four: How to Get Away With Murder, a "sexy, suspense-driven legal thriller" starring Viola Davis.

In less than a decade, Shonda Rhimes has become one of television's top showrunners (an industry job indicating a show's most powerful creative), building an empire on sexy relationship drama and increasingly absurd dangers.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While it keeps her shows popular, however, Rhimes' over-the-top drama actually masks the rich potential of her point of view. Yes, she kills off a lot of people in spectacular fashion, and her dramas have a tendency to quickly boil into furious crescendos of insanity. But they also stretch the boundaries of character and context, diversity, and social boundaries far beyond the norms of television. If even some of the sensationalism was traded for more measured and serious storytelling, Rhimes' empire could easily morph into one of the most impressive on television.

Grey's Anatomy began as a very human story of newbie surgeons, led by Meredith Grey, who struggle to become professionals and adults — facing the pressures of caring for parents, of adult relationships that come with expectations, of home ownership, money, and responsibility. But as Meredith dealt with her life's many problems and her increasing death wish, the tide turned, and a quiet show — which needed nothing more than a simple STD outbreak to end its first season — became a series in which its hero literally held her life in her hands, clutching a piece of live ammunition embedded in a man's body.

It was a disheartening change. In a world where each television event must be bested, Grey's Anatomy quickly spiraled into an onslaught of ever-increasing romantic and deadly angst as the surgeons faced multiple bus and plane crashes, crazed gunmen, explosions, electrocutions, and more.

If anything can match the show's histrionics, however, it is its commitment to rebirth. Grey's Anatomy has lasted this long because it is continually reincarnated. Watching different seasons is almost like watching different shows — the newbie years, the drama years, the tear-jerking years, the devastation years. Rebirth fuels the show thematically, and it is part of Grey's larger commitment to reinvent cultural and interpersonal expectations about television.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Rhimes was given exceptional leeway from the get-go, when ABC told her to "go for it" and cast without character descriptions, reading "every color actor for every single part." The result was an unusually diverse mix of residents and interns. The hospital was run by several black characters: a Chief of Surgery (James Pickens Jr. as Richard Webber), an attending cardiothoracic surgeon (Isaiah Washington as Preston Burke), and the attending surgeon of the interns, Miranda Bailey (Chandra Wilson). Coming from a woman of color, it seemed like a calculated move, but as Rhimes explains it, she had expectations for some of her characters, but casting took a life of its own. "I pictured [Bailey] as a tiny blonde with curls … but then Chandra Wilson auditioned."

The depiction of platonic relationships on Grey's Anatomy proved similarly groundbreaking. Rhimes plays by her own rules in her personal life (choosing to adopt as a single mom rather than wait), and her characters follow suit.

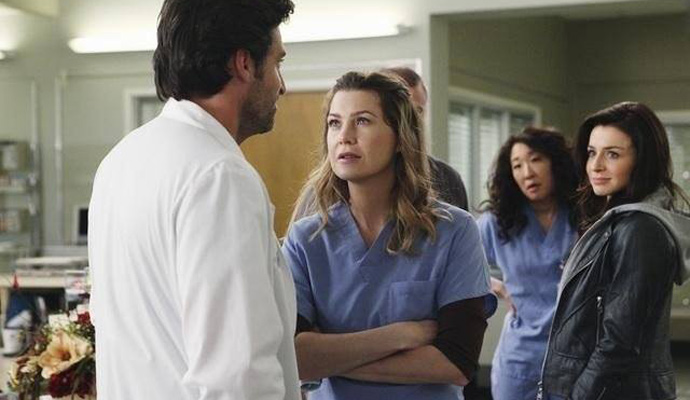

Grey's immediately set up Meredith's romantic life with the "McDreamy" Head of Neurosurgery Derek Sheperd (Patrick Dempsey), which became the relationship many fans and critics focused on. But the series also gave Meredith a best friend and chosen family member in her fellow intern Cristina (Sandra Oh). In the series' first season, Cristina tells Meredith, "You're my person," cementing a friendship that became Grey's secret backbone. Through drama, angst, and happiness, the pair rely on each other, and they remain each other's "person," prone to speaking their own idiosyncratic language and having sleepovers and private dance parties even as they move forward in their personal and professional lives.

"You're my person," in turn, became a rallying call for many of Rhimes' characters, whose families, romances, and friendships don't always follow the cultural norm. In another storyline, Latin surgeon Callie (Sara Ramirez) turns an awkward one-night-stand with her best friend Mark (Eric Dane) into a happily unique three-way parenting structure when she marries girlfriend Arizona (Jessica Capshaw). The transition isn't easy, but it's possible because the characters do what works for them, not for others.

In Grey's Anatomy, families and commitments are chosen, and they rise above the repetitive storylines of jealousy, abandonment, and battle that make up most TV dramas. The only thing that challenges these unique but powerful bonds is what Rhimes can't control: actors leaving, such as original interns Katherine Heigl and T.R. Knight. Callie's trio came to a close when Dane left the series, and sadly, Meredith's is following suit this season as Oh bids the show adieu.

Breaking out of the medical world and into political drama with Scandal allowed Rhimes to take the next step, diving headfirst into professional fixer Olivia Pope and her world of grey — where absolutely no one is all good or bad, but merely the result of their experiences. In any given episode, the good might be tantalized by the bad, or the bad might turn out to have utterly relatable skeletons in their closet that leads the viewer to reinterpret their every action. Scandal teases our rampant need to categorize, calling everything into question with skilled, charismatic actors Hollywood has generally underutilized — talents like Jeff Perry, Khandi Alexander, and the incomparable Joe Morton.

In one of the show's most poignant twists, irascible First Lady Mellie Grant (Bellamy Young) suddenly evolves from a cold and power-hungry wife to a real, relatable woman. Mellie does many loathsome things — but over and over, Rhimes finds opportunities to give her bitterness some background. Mellie's anger doesn't only derive from giving up her profession and skill set to be a smiling presidential wife, but from the humanity she needed to give up to do it. Scandal has depicted Mellie shouldering responsibility for the dirty work that has to be done, forced to stay silent as her husband openly pines for Olivia, and much worse: Keeping silent about her rape to avoid worrying her husband.

As an established showrunner, Rhimes also has the freedom to overtly play with race and culture, and not just diversify the networks' typical output. Scandal's Pope family — Kerry Washington's Olivia, and her deadly parents Rowan (Joe Morton) and Maya (Khandi Alexander) — allow for the kind of multigenerational racial interaction that's rarely depicted on television. Rowan and Maya's generation of black Americans, who faced genuine danger for the gains they accomplished, now crash up against Olivia's new generation, who employ wordy banter and political maneuverings as their weapons. When Morton condescendingly retorts "Oh, to be young, gifted, and black" in the recent season finale, he's not just being the snarky Papa Pope. It's a quote from Lorraine Hansberry and Nina Simone — a line that emphasizes the modern cultural divide while simultaneously nodding to the work that came before.

Unfortunately, all those nuances have become overshadowed by lurid, event-driven storytelling. Like Grey's Anatomy, Rhimes quickly eschewed the more grounded, case-by-day maneuverings of Pope and Associates in Scandal. In less than 50 episodes, the show's small group of characters has experienced a mix of murder, espionage, blackmail, rape, and terrorism — and that doesn't even really begin to scratch the surface.

But what if a Rhimes show didn't devolve into its ever-increasing game of "shocking" one-upmanship?

If you can scrape the super-drama away, Rhimes' output offers compelling dynamics worthy of both ratings and critical success — especially in Scandal — which delves into politics, sexism, and even one woman's (Quinn Perkins) gradual devolution from innocent victim to dangerous hitwoman. Underneath the endless twists and turns, this is the rare popular mainstream series about a dynamic black family, bringing black culture into the mainstream conversation the same way The Cosby Show did 20 years ago.

Between the success of Grey's Anatomy and Scandal, Rhimes has proven that her viewpoint is not a risk, but a bankable vision. The real risk now is not diversification or alternative lifestyles; it's removing the pulp craziness and slowing down the narrative to focus on the truly interesting elements of her stories.

Slice away some theatrics, and Rhimes would easily be on the Writers Guild's list of best shows, mentioned alongside hits like The Sopranos and Breaking Bad. With a little less "event" and a little more storytelling, Rhimes could offer series that finally rid television of its repetitive norms.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown