Wounded in Boston, two brothers endure

The Norden brothers each lost a leg in the Boston bombing. Their new lives are hard.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

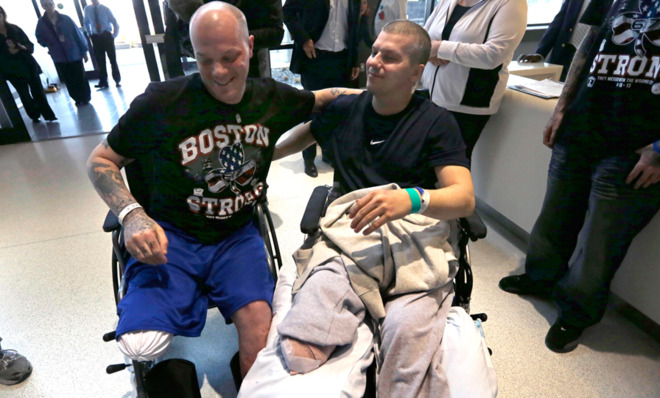

WHEN TWO BOMBS transformed last year's Boston Marathon into a war zone, the Norden family absorbed a double dose of grief. J.P., 34, and his brother Paul, 32, strapping construction workers in their prime who were there to cheer on a friend, each lost a leg in the carnage.

Since then, they have slowly, achingly, been rebuilding their lives. After lengthy hospital stays and more than 50 surgeries between them, they are walking on prosthetic legs. They talk of starting a roofing business together. Both have moved out of their mother's house and are living with their girlfriends. Paul is engaged.

The Nordens do not want to dwell on what happened at the marathon or be defined by it. But the approach of the first anniversary pulled them in. The occasion has assumed enormous symbolic significance as the survivors and Boston itself are determined to show their defiance and resilience. The formal observance stretches out for almost a week starting on April 15, the date of last year's bombings — which killed three people, wounded at least 260, and robbed 16 of various limbs — and continuing through April 21, the date of this year's marathon.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Like many others, the Nordens have been overwhelmed by the attention the anniversary is drawing. Tributes, panel discussions, concerts, fundraisers, and television specials crowd the public calendar. And because the Nordens are promoting a book about their experience, the demands on their time have intensified. For them, the anniversary is a hump to get over. For now, the brothers have no time to go to the gym. They have postponed needed surgeries. Paul and his fiancée, Jacqui Webb, who was also wounded in the blast, have delayed planning their wedding.

Liz Norden, 51, a single mother of five, said that with her boys, as she calls them, on the mend, she has begun to grieve. "Now is the time where everything comes into play — my emotions, their emotions, the anniversary, the media," she said. "It builds up. I cry now at the drop of a hat."

THE FIRST EXPLOSION, a block from where they were standing, confused J.P., Paul, and Jacqui. As other spectators, screaming, began to flee, they tried to do the same. Paul and J.P. started to hoist Jacqui over metal barricades and into the street. Twelve seconds later a second bomb exploded outside the Forum restaurant, just a few feet from the Nordens and from 8-year-old Martin Richard, one of those killed in the blast.

J.P. lay on the sidewalk.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"I tried to get up on this leg first," he said the other day, gesturing to his right leg. "I couldn't. And I looked down and it was gone and I couldn't get up. My pants were on fire. My shirt was on fire."

He rolled over to smother the flames and was quickly surrounded by medics and bystanders who whipped off their shirts and belts to apply as tourniquets to both his legs. He was soaked in blood. By the time he arrived at the hospital, he was barely alive.

Paul was a few feet from J.P., sitting up but dazed. He stared at his right leg, off on its own, lying in the street with other detritus from the blast.

"My mind wanted me to reach for it, but my body wouldn't let me," he recalled. Neither brother could hear much; the explosion had punctured their eardrums.

The blast propelled Jacqui into the street, where she landed on her hands and knees. Her hands were burning so hot that her rings began to melt, and her right leg was gouged with shrapnel.

The brothers were taken to different hospitals. J.P.'s girlfriend, Kelly Castine, stayed with him all 45 nights that he was hospitalized; Jonathan Norden, 28, the youngest of the brothers, stayed with Paul all 31 nights of his hospitalization.

They are called survivors because they lived. But there were moments when Paul, whose right leg was amputated above the knee, said to himself that he wished he had not.

"I was in the shower one day and my mother had to come in and help undress me, and that's wicked hard," he said. "I really was so depressed, I wish I didn't live." Another time he fell in the snow and was so embarrassed that he pretended he was making snow angels and had fallen on purpose.

"I'm not suicidal," he said. "I'm happy most of the time. But it's so frustrating when you can't do what you want to do. You feel like you're not even a man."

That feeling does not last. Paul, who is 6 feet 2 inches and has a close-shaved head and arm-sleeve tattoos, is easily recognizable and frequently greeted by strangers. Often, those strangers say he is an inspiration. "Maybe I'm helping them in some way," he said.

Before the marathon, Paul said, he was complacent about life and didn't see much purpose in it. "I didn't care," he said. "Like, I wasn't sad, but I wasn't thrilled, like, 'Oh, my life's awesome.'"

Now, he sets goals — getting out of the wheelchair, losing the crutches, walking the dogs. "Me and my brother, we're happy and motivated to do things every day because we're obviously lucky to be alive," he said.

It is important to him to be able to walk on his own. "I don't want people to think I'm handicapped or disabled, because I'm not," he said. He realized what he had just said and laughed. "Like, I am — but I'm not."

THE ONE FUND Boston, the main fund-raising effort for marathon bombing victims, distributed more than $61 million last summer to 230 people. The Norden brothers each received $1.2 million. Given their lifetime expenses for medical bills and prosthetics, the brothers are saving that money.

"I would be scared to use it or blow it," J.P. said. "I don't know what my life will bring, I don't know how work will be, I don't know what type of job I'll be capable of working."

It is odd having to dedicate their so-called windfalls to something they would rather not have and are still getting used to. This is especially true for J.P. Although his amputation was below the knee and considered less traumatic than his brother's, he was more gravely injured overall and took much longer to get back on his feet. Paul started walking on his new leg on June 23; J.P. could not do so until the beginning of March.

One of the hardest circumstances, J.P. said, is being in bed when he needs to use the bathroom. He has to turn on the light, prepare his stump, put his leg on, get to the bathroom, get back, and take off the leg. By then he is wide-awake. Instead, he uses a urinal but is trying to learn to put his leg on faster.

The brothers received their first legs free. But amputees need new legs every three to five years, and insurance generally covers only part of the expense. The cost varies depending on the person's weight and activity, said Kevin Carroll, vice president of prosthetics for Hanger, a Texas-based company.

A leg for J.P. could range from $7,000 for a basic model to $25,000 for one with high functionality, Carroll said; the top version could cost $40,000. A leg for Paul is more complex. Prices start at $20,000 and might average $38,000, while the top-of-the-line model runs $125,000.

Paul's right leg, now vanished, had been an engine of his happiness, propelling him through what he called his "average" life — the days of playing basketball and of walking his dogs.

In its place now is a sophisticated prosthetic powered by microprocessors and programmed to follow his gait. It is waterproof, which means he does not have to remove it to shower.

"Some people say that's a luxury," Paul said. "A luxury would be having my own leg back."

LIZ MOVED INTO a handicap-accessible house a few months after the marathon. But when Paul and J.P. first got out of the hospital, they went to her former house in nearby Wakefield. Its bedrooms were upstairs, giving Liz an endless workout.

"I was like, 'Ma, could you bring up my bag of pills?'" said J.P. "'Ma, can you do this? Can you do that?' Or I'd ring a bell or text her. 'Ma, I'm in bed and can't get up again. Can you bring up my water?' And she would do it."

"I did it your whole life!" his mother interjected, good-naturedly. "Nothing has changed!"

Joking aside, she said she would do anything for her boys. "But to me it's sad because they're adults," she said. "There were times when you'd have to help Paul put his leg on. He's 32. He doesn't want his mother doing that." As close as they are, she said, "sometimes you don't know what your place is."

Paul can hardly find the words to describe all that his mother has done. "She's meant the world to me my whole life," he said. "I suffer from a lot of anxiety stuff, and she's just always there for me."

The recent publication of the brothers' book, Twice as Strong, has pulled all the Nordens into the media swirl. They know that to promote the book, revenue from which will defray their medical expenses, they must be available for interviews. And they want to use the exposure to thank the thousands of people who have donated time and money to improve their lives.

"You realize what good people there are in the world," said J.P. "You shouldn't wait for a tragedy to have to know that, but that's what it took for me to find that out."

Still, the brothers wonder sometimes what more there is to say. Sometimes, when the occasion calls for an upbeat appearance, they are just too exhausted. Paul received an email recently saying that the Red Sox had invited bombing survivors to the team's home opener at Fenway Park; he deleted the email without telling his brother.

Dr. Chris Carter, a rehabilitation psychologist and part of the team that treated the survivors, said such reactions were normal and that survivors were smart to power down until the anniversary was over. "Get through this, let yourself recover, and pick up the battle afterwards," he said.

Some survivors are determined to attend the marathon, which may draw a record 1 million spectators this year. Others are recoiling. Some are not sure. Carter said that Boston, as part of its own healing process, wanted to see that the survivors were making progress; at the same time, he said, some of them "have days when it's hard, there's a lot of pain, fear, anxiety, and doubt that they can do it."

J.P. is uncertain about attending. But Paul and Jacqui plan to go to support his nurse, who is running to raise money for the brothers, and to support Mike Jefferson, the friend whom they came to see last year but who was stopped by the explosions just before he reached the finish line. Liz has no intention of going anywhere near the race.

Adapted from an article that originally appeared in The New York Times.

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more