Matt Taibbi on vampire squid, journalistic outrage, and Obama's flaccid approach to financial crime

"Somebody out there is getting screwed."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Matt Taibbi is still fuming about the "vampire squid" of high finance.

The Rolling Stone reporter who famously tagged Goldman Sachs as "a great vampire squid, wrapped around the face of humanity" — a phrase that is now so embedded in the cultural lexicon that he wonders if it will be on his gravestone — is well-known for his polemics against banks and Wall Street's bad actors. For his new book, The Divide, he decided to carry that journalistic interest to its logical extension.

Taibbi's book is about the wealth gap in the U.S., the people who play fast and loose with the rules — the wealthy and banks with armies of lawyers, for example — and how they rarely seem to have to face the music.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"One of the things that happens when you stop going after high-ranking white-collar criminals is that the public slowly becomes inured to the fact there's a difference in the way we treat one kind of offender versus another kind of offender," Taibbi told The Week in a recent phone interview. "Yes, the rich have always been better off than the poor. What's different now, though, is that the government no longer feels the necessity — one might even say the symbolic necessity — of going after the worst of Wall Street and pharmaceutical companies. But in order for the public to have confidence in the justice system, you have to go after the people who commit crimes."

The Bush administration, he says, was much tougher than the Obama administration on corporate malfeasance, going after companies like Enron, Tyco, and WorldCom. The Obama administration, Taibbi says, has taken a kids' gloves approach to prosecuting financial crime. Underscoring the point, since 2009 the FBI has closed almost 750 mortgage fraud cases with "little or no investigation."

No surprise, Taibbi writes, that Americans have thus "learned to accept the implicit idea that some people simply have more rights than others. Some people go to jail, and others just don't … We've arranged things so that the problem is basically invisible to most people, unless you go looking for it.

"I went looking for it."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

An episode in the book that crystallizes Taibbi's point comes about a third of the way through, when Taibbi introduces himself outside a courtroom to a lawyer who defends the poor. They have a conversation where it becomes clear the lawyer doesn't seem concerned with making sure the scales of justice tip in his clients' favor. "Low class people," he tells Taibbi, "do low class things."

"We still have real jury trials, honest judges, and free elections, all the superficial characteristics of a functional, free democracy," Taibbi writes. "But underneath that surface is a florid and malevolent bureaucracy that mostly (not absolutely, but mostly) keeps the rich and poor separate through thousands of tiny, scarcely visible inequities."

"I get asked a lot, 'You describe a lot of problems — how come you're not out there as an activist?'" he tells The Week. "My job, though, is to describe what is, and explain it for people. It is kind of depressing right now. Things are heavily slanted in one direction, which is difficult. One of the things I think about when I work is that the people who are sort of very wealthy, they have all sorts of media outlets pushing their point of view. They don't need me to do that. Other people do. I try to push in the other direction to make up for that propaganda gap."

The release of The Divide comes at a time when Taibbi is helping launch a new digital magazine for Pierre Omidyar's First Look Media that will focus on Taibbi's bailiwick of financial and political corruption. Taibbi tells The Week that the new enterprise — no word on the official launch date yet — will see him serve as the editor-in-chief, but he'll be reporting and writing as well.

Its tone won't exactly resemble that of his usual searing takedowns, but will be a tad puckish. "It'll be sort of the same approach as The Daily Show," he says.

"A journalist, though, does have to keep in touch with his sense of outrage — I'd call it a critically important element to do this job correctly," he says. "It does happen to people, where you get corruption fatigue, and it happened to me in this instance a little (with The Divide). I read about a welfare mom who lost her kids because of a welfare fraud case — a small case. But we wouldn't consider that (former Countrywide CEO) Angelo Mozilo should lose his kids, even though he created the biggest fraud case in the history of the world. So, somebody out there is getting screwed."

As completely as he has immersed himself in covering and understanding Wall Street and its various financial scandals, it might seem surprising to hear that Taibbi says it actually all began by accident.

"Up to that point, I was basically a political humorist, making trenchant remarks and that sort of thing," Taibbi says. "During the 2008 election season, that happened to be the time when the economy melted. I remember trying to understand what was happening, and none of the coverage made any sense. Underneath the dumb and superficial surface of this left-right, adolescent schoolyard fight we have, it struck me that when the crash happened — 'This is it. This is the complicated stuff that I was sure had been there the whole time.'"

He has some advice for young, aspiring journalists: at the top of the list, go overseas.

"It's great life experience, you'll have fun and you get a different perspective on the world and learn how the world works," he said. "You need to be able to instantly diagnose and understand situations, and it's impossible to do that if you only have your own way of looking at things."

-

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg

-

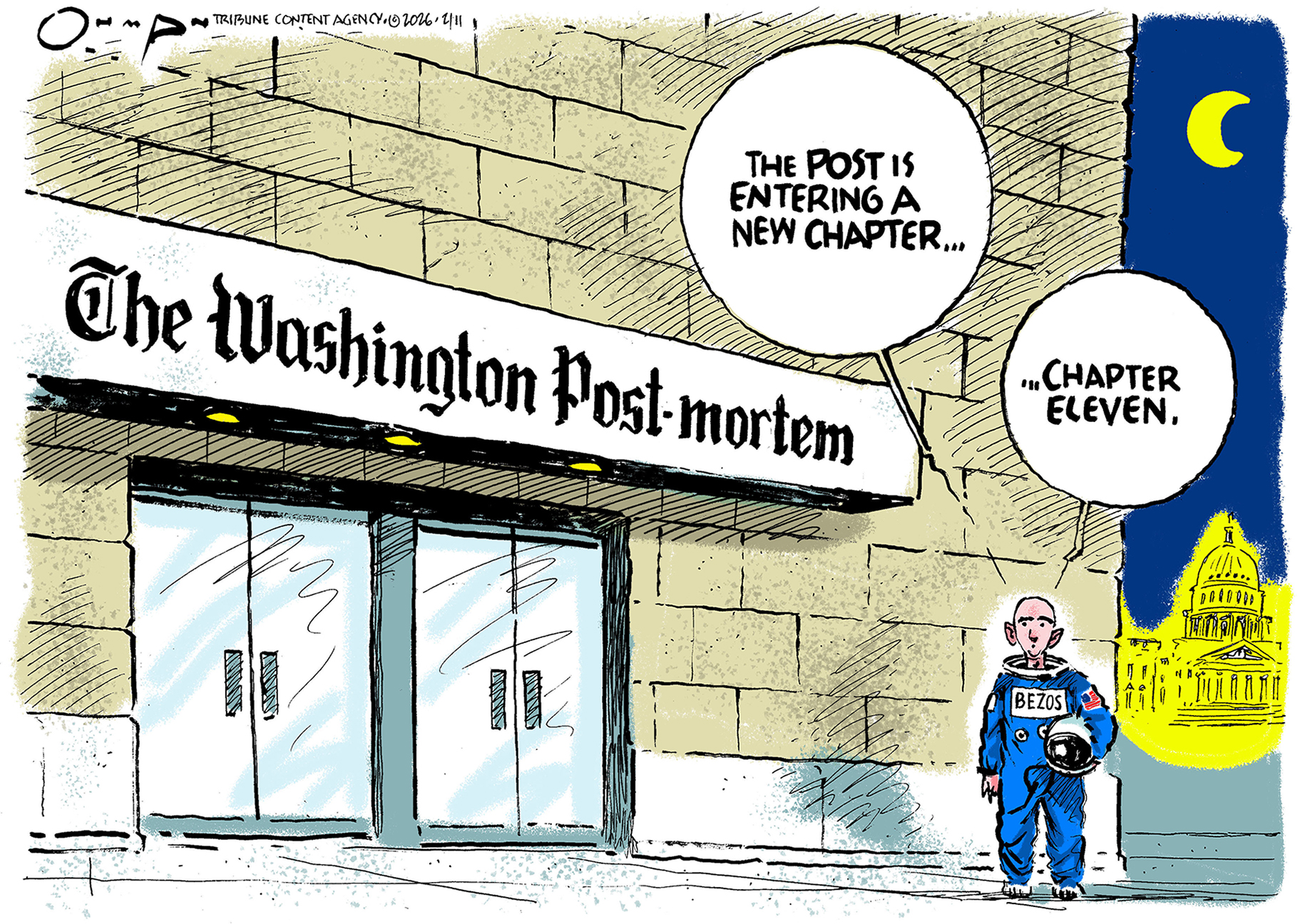

5 calamitous cartoons about the Washington Post layoffs

5 calamitous cartoons about the Washington Post layoffsCartoons Artists take on a new chapter in journalism, democracy in darkness, and more

-

Political cartoons for February 14

Political cartoons for February 14Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include a Valentine's grift, Hillary on the hook, and more