If a nuclear bomb exploded in downtown Washington, what should you do?

The WORST thing you could do is get in a car and drive away

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Funny question in the headline, yes?

But since President Obama worries more about the threat of terrorists' improvised nuclear device going off in a major American city than anything Russia can throw at us, I was wondering if the government had deigned to share with us citizens any tips for, you know, surviving something their own intelligence points to as the likeliest unlikely Black Swan event.

Well, no. And yes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

No — very few people in Washington, D.C., who work for the government have any idea what they would do if a 10-kiloton nuclear device exploded at the intersection of 16th and K streets.

You can always look to movies to figure this stuff out, right? And in movies, since nuclear radiation is BAD, the thing to do is to get away from it as quickly as possible. In the movies, electronics are fried, too, the response is chaotic, and hundreds of thousands of people die.

Interestingly enough, though, the government has done quite a bit of work to figure out what exactly would happen if a suitcase nuke — which, I know, doesn't really exist, but, for the sake of this example, bear with me — actually did explode a few blocks from the White House.

And curiously, and perhaps hearteningly, it turns out that there is quite a lot that you or I can do if we get stuck in Washington when something like that happens. Choices we make could very well make the difference between our imminent death and a relatively full and happy life, assuming the bomb is a one-off.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory released a report in 2011 that spells all this out. It hasn't gotten nearly the attention it deserves.

It's called the "National Capital Region Key Response Planning Factors for the Aftermath of Nuclear Terrorism" and it makes for fascinating reading.

Did you know, for example, that:

1. The WORST thing for someone to try to do, in the aftermath of a nuclear explosion that they survive, is to get in a car and drive away.

2. Unless you're within about a third to a half a mile radius of ground zero and the shelter options are poor, the BEST thing for someone to do is to find a stable location inside a well-built apartment or office building — the majority of which will remain standing outside that half mile radius — and stay there for 24 hours.

And if you were very close to ground zero and you did survive — and a lot of folks will — the best thing for you to do is to:

A. Take immediate shelter somewhere, because fallout will rain down on you if you don't.

B. Wait an hour.

C. Then, walk about a half-dozen blocks laterally until you find intact large buildings to shelter you.

3. The electromagnetic pulse from a ground burst will NOT, in fact, knock out all types of communication. Some? Maybe.

4. If you live in a single-family house with thin walls, your chances of surviving in the immediate aftermath of a blast and not getting cancer later are exponentially higher than if you seek shelter in a bigger building, even one that might literally be next door.

5. Rescuers should NOT put on radiation protection gear if it will slow them down. So long as the fallout has stopped falling, they're best advised to turn out in their normal gear.

6. Though thousands of people will die from the blast effects, almost all — about 96 percent — of the other potential casualties could be avoided if people understood the basics of what to do in the event of mass radiation exposure.

7. Did I mention that the worst place to be in the immediate aftermath of a nuclear blast is in a car trying to get away? The so-called DFZ — the Dangerous Fallout Zone — will extend out as much as 20 miles, but it is likely to be extremely narrow. (If it's not, that means the concentration of radioactive particles will be lower.) The vector and location of this zone depends on the wind. And its size will shrink with every passing hour.

8. Penetrating trauma from broken glass is probably the largest treatable cadre of blast injuries.

I admit that I don't know what forum the president or anyone else could use to educate people in major cities about this stuff. Government never wants to alarm people. But maybe a little bit of alarmism is worth it, if it turns out that a terrorist's nuclear blast is a lot more survivable than we might think, if only we do certain things.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

The recycling crisis

The recycling crisisThe Explainer Much of the stuff Americans think they are "recycling" now ends up in landfills and incinerators. Why?

-

The L.A. teachers strike, explained

The L.A. teachers strike, explainedThe Explainer Everything you need to know about the education crisis roiling the Los Angeles Unified School District

-

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years ago

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years agoThe Explainer Here's what they did about it

-

America's homelessness crisis

America's homelessness crisisThe Explainer The number of homeless people in the U.S. is rising for the first time in years. What’s behind the increase?

-

The truth about America's illegal immigrants

The truth about America's illegal immigrantsThe Explainer America's illegal immigration controversy, explained

-

Chicago in crisis

Chicago in crisisThe Explainer The "City of the Big Shoulders" is buckling under the weight of major racial, political, and economic burdens. Here's everything you need to know.

-

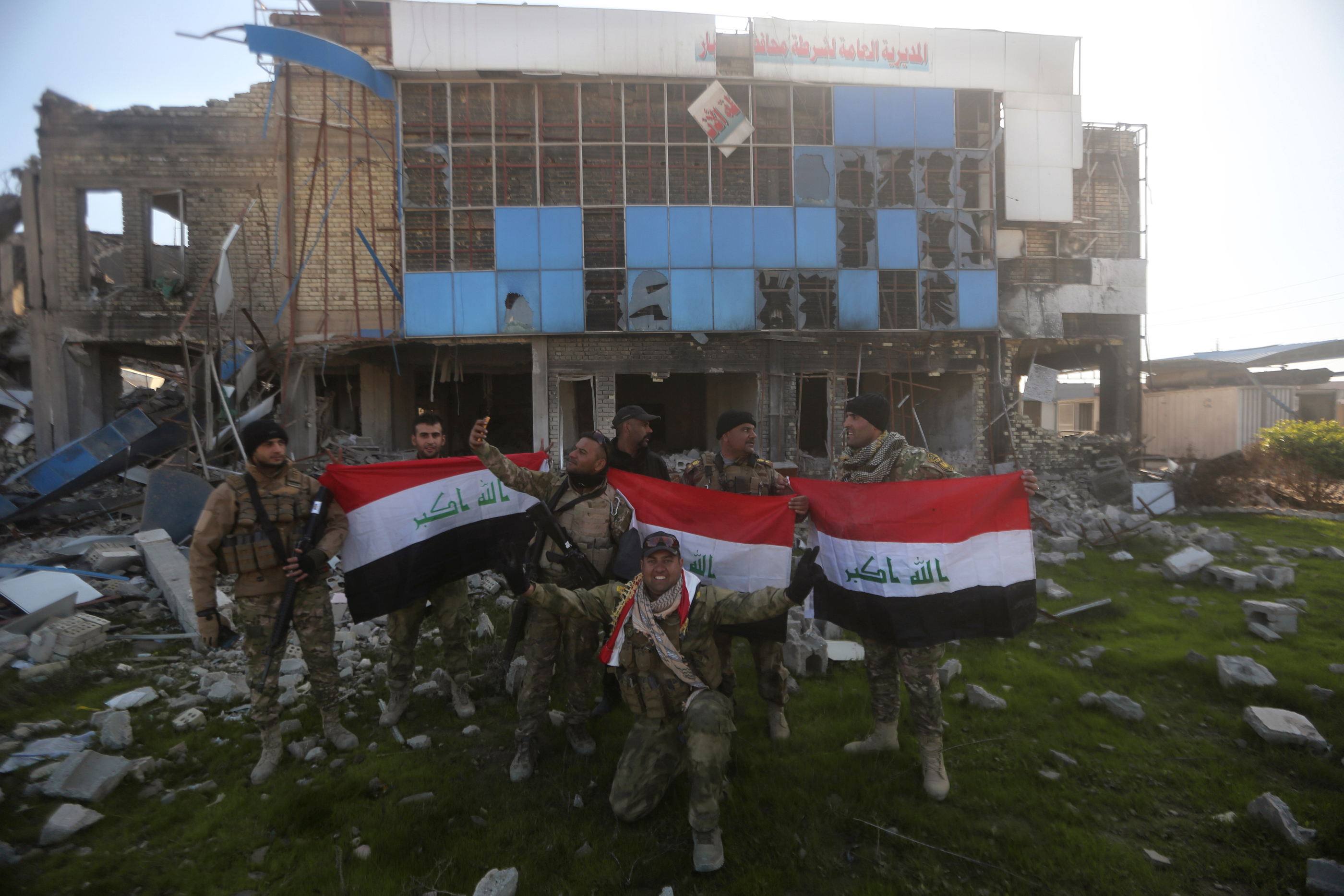

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in Ramadi

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in RamadiThe Explainer The contours of a broader sectarian war are coming into focus

-

America can still destroy the world

America can still destroy the worldThe Explainer The decline of U.S. military power has been greatly exaggerated