Why Dr. Strangelove is more depressingly relevant than ever

Fifty years after its release, Stanley Kubrick's Cold War classic still has plenty to teach us about global politics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

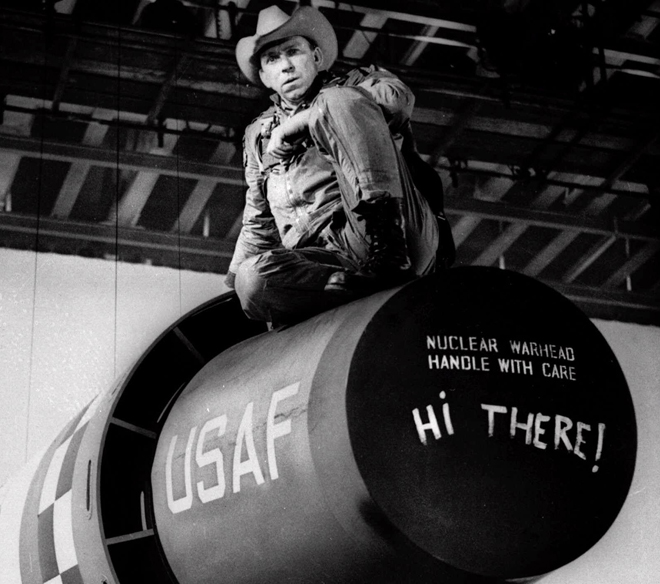

It was just 50 years ago that Stanley Kubrick’s legendary satire Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb hit theaters — but the world was a very different place. The Cold War was at its height, and America was still recovering from the assassination of President John F. Kennedy just two months earlier. It’s into this charged landscape that Stanley Kubrick launched Dr. Strangelove, a jet-black comedy that gave voice to the nerve-jangling paranoia of the era.

Dr. Strangelove, which loosely drew inspiration from Peter George’s 1958 novel Red Alert, follows an all-too-plausible doomsday scenario in which a rogue commander sets the U.S and the Soviet Union on an inescapable path to mutually assured destruction. Described by one critic as "the most shattering sick joke I've ever come across," Dr. Strangelove mercilessly spoofs the military and political insanity of the age, laughing at the prospect of nuclear destruction at a time when drills, fallout shelters, and public safety warnings were a reality of everyday life.

It was a risky choice, but it paid off; Dr. Strangelove is now justifiably recognized as one of the greatest satires ever to grace the screen. When the film is discussed today, viewers tend to see it through the haze of a bygone Atomic Age. But like all great satires, there are plenty of aspects of the film that remain both hysterical and frightening. Fifty years from its original release, the message of Dr. Strangelove remains depressingly relevant — and this is why:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

1. There are still a lot of nuclear weapons in the world

In the decades since Dr. Strangelove’s release, there have been significant reductions in warheads across the globe. But more than two decades after the end of the Cold War, the world’s combined nuclear arsenal remains disturbingly high. It’s estimated that some 17,000 warheads are currently stockpiled around the globe, of which around 1,800 remain on high alert, ready to be fired at a moment’s notice. In addition, the government continues to plow billions of dollars into projects such as the so-called "Star Wars" missile defense system (an idea first dreamt up by the Reagan administration in 1983).

These days, of course, Russia isn’t the most troubling atomic aggressor; it’s rogue states and emerging nuclear powers, like Iran and North Korea. But while the players have changed and public paranoia has diminished, the Doomsday Clock remains rooted at five to midnight — a reminder that mankind is arguably as close to mutually assured destruction as we were at the time of Dr. Strangelove’s release.

2. The technology of war

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

From doomsday machines to a Jumbotron-filled war room with a strict "No Fighting" policy, technology is at the heart of Dr. Strangelove’s dark narrative — particularly when it malfunctions. One of the film’s central themes is the deeply flawed technology of war, which puts real power in the hands of fallible machines, not to mention armchair generals holed up in windowless bunkers thousands of miles away from the front lines. Fast forward 50 years, to an age where drones have become commonplace, and you don’t have to look hard for a parallel.

3. Human fallibility

"I admit the human element seems to have failed us here," says Dr. Strangelove’s General Turgidson, played by the brilliant George C. Scott. It’s a sentiment that echoes throughout Dr. Strangelove. The mental illnesses, testosterone-fuelled saber-rattling, and downright stupidity of a few high-level players can set humankind on a course to nuclear obliteration. Half a century later, the human race is no less fallible — and whatever your politics, you need only to turn on the news for to get a stark reminder of mankind’s continued propensity for self-destruction.

4. A culture of fear

No, the United States is no longer immersed in a Cold War with "Rooskies" or "Commies" who are intent on "impurifying our bodily fluids." But the culture of fear that drives in Dr. Strangelove is still an ever-present part of our lives. From the ongoing "War on Terror" to chronic tensions with North Korea, unseen enemies continue to drive public paranoia in a way that makes Dr. Strangelove darkly relatable. In the years since its release, collective fears about ideological enemies have continued to fuel policy-making, from the invasion of Iraq to the expansion of the surveillance state.

5. Government distrust

Dr. Strangelove goes out of its way to undermine each and every authority figure that it puts on screen: Psychologically unstable generals, drunken world leaders, and armchair commanders whose opinions are directly informed by agenda-driven think tanks. Kubrick’s film shows us a world where there’s an entirely justified suspicion of the people whose fingers are on the triggers. If that sounds familiar, that’s probably because it hasn’t changed much: If recent reports of record levels of government mistrust are to be believed, things are worse than ever.

Daniel is a freelance writer, an Englishman abroad, and a pop culture junkie. He writes about film, TV, and lifestyle for outlets including MSN, The Guardian, The Times, The Independent, The Evening Standard, and Yahoo.

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West