Is there any hope for the Syrian peace talks?

The United Nations' bumbling disinviting of Iran underscores the Keystone Kops quality of Geneva II

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

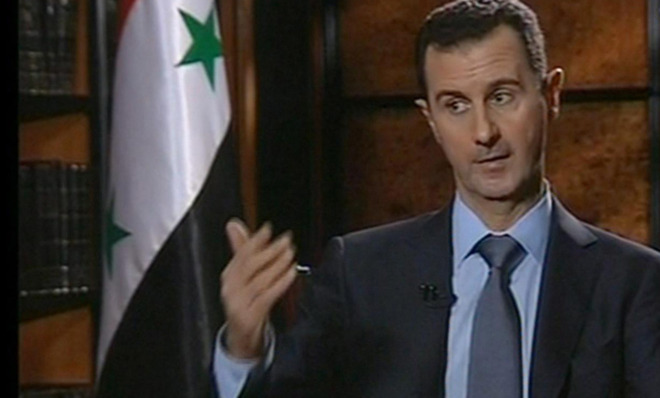

The long-awaited peace talks between the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the rebels trying to overthrow him starts Wednesday in Switzerland. Hopes aren't terribly high for the first face-to-face meeting between the two warring sides in the nearly three-year-old civil war. Indeed, the entire conference almost fell apart this week, after United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon invited Iran to participate.

Late Sunday, Ban extended the invitation for Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif to attend the meeting, saying Tehran had agreed to play "a positive and constructive role." Ban suggested that Iran had signed off on the goal of the conference: that Syria switch to a transitional government of "mutual consent" by the Assad regime and opposition forces.

Syria's rebels and Saudi Arabia threatened to boycott the talks over the invitation, since Iran is sending arms and paramilitary forces to support Assad. The U.S. also strongly objected, saying Iran had to publicly support the conference's objectives. And then Iran essentially defused the situation on Monday by saying it had never agreed to any conditions for taking part in the talks and didn't agree to the stated goals. Ban, furious over Iran's public disavowal of privately agreed-upon terms, promptly disinvited Iran.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

University of Ottawa political scientist Stephanie Carvin captures the flavor of the episode:

But the Geneva II talks faced steep odds even before the Iran debacle. "It is, in fact, hard to imagine a peace conference that has been convened under less propitious circumstances," say Michael R. Gordon and Anne Barnard in The New York Times.

In 2012, when the groundwork for the talks was laid at the Geneva I conference, Assad was pretty isolated internationally. His main allies were Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah. The opposition seemed promising, and likely to get U.S. and European backing. The U.S. was threatening force if Assad crossed a "red line" of using chemical weapons on his people.

Now, Assad and his allies are on the offensive, the opposition is divided by infighting, and Syria has gained back some stature and defused U.S. missile threats by ostensibly giving up its chemical weapons.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In an interview before the talks, Assad told the AFP that there's a "significant" chance he'll seek re-election in June. He also said the goal of the Switzerland meeting was to deal with Syria's "war against terrorism," and deemed it "totally unrealistic" that he would share power with the opposition group that is showing up at Geneva II.

So, is there any hope for the Syrian peace talks?

Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov said it was a mistake to disinvite Iran from the talks, "but it isn't a catastrophe." That may seem like an easy prognosis from a country whose ally in the fight seems to be winning. But "the Russians are actually quite interested in this Geneva process, and the Syrian government is not," former State Department Mideast adviser Jeremy Shapiro tells Germany's Deutsche Welle. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry might even be able to use that discrepancy as a "wedge" to drive apart Russia and Syria, Shapiro adds.

The U.S. State Department itself argues that the talks are worthwhile because the international push for a new transitional government may encourage defections from Assad's side. "There are elements inside the regime itself, among its supporters, that are anxious to find a peaceful solution, and we've gotten plenty of messages from people inside; they want a way out," an identified State Department official tells The New York Times. "That's the whole point of their going to Geneva.... To promote the alternative, the alternative vision."

Faisal Al Yafai at Abu Dhabi's The National even asserts that in the run-up to the talks, Assad made a major tactical error in agreeing to a ceasefire in rebel-held Aleppo. Yafai doesn't expect Assad to honor the truce, but says it doesn't matter: Syria has unwittingly "opened the door again to military intervention."

If the opposition and its backers in the international community are canny, they will push the Security Council to adopt a resolution deciding ceasefire terms for the city. Russia, as Syria's backer among the permanent five members, can hardly object to such a resolution. With a resolution in hand and with international backing, there could be all sorts of opportunities to police the ceasefire — with the ability, later, to go back to the Security Council for a further resolution if Mr Al Assad were in breach. The door to strong international action is suddenly open again. [The National]

Yafai notes that the internationally brokered ceasefire that Iraq agreed to after its Kuwait invasion in 1991 was the basis for the 2002 Security Council Resolution 1441, which provided "flimsy, but legally crucial, cover for the invasion" of Iraq in 2003.

But probably the greatest realistic hope for Geneva II is an agreement to open up medical and food aid corridors, prisoner exchanges, or more durable humanitarian ceasefires to help address the steadily worsening plight of Syria's civilians. And at the very least, the talks will put Assad and opposition representatives across the table from each other for the first time since the bloody civil war started three years ago.

"In a lot of cases, these meetings, whatever their sort of titular purpose, are more to ensure there's some sort of dialogue — that lines of communication stay open and you make limited progress," former senior U.S. official Anthony Cordesman tells Deutsche Welle. "That doesn't always produce quick results."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?