Can this bracelet replace heaters?

Now you can hack your body

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We've all been there. Someone, who senses that the room temperature is a bit too cold, decides to turn down the air conditioning. All of a sudden, another person in the building complains that it's too hot. Uh-oh!

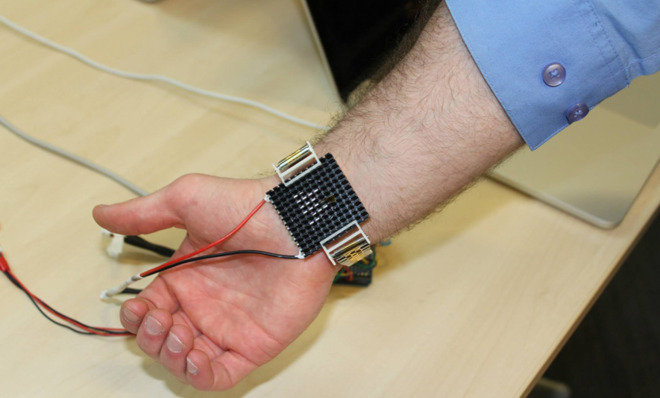

It was this all-too-common predicament playing out six months ago amongst students in an MIT engineering lab that was the genesis for the creation of a device called Wristify, a simple bracelet that's designed to instantly allow the wearer to feel cooler or warmer by sending out alternating pulses of hot or cold to a small area of skin right beneath. As kooky as it sounds, the research team, along with other volunteers who have tried out the invention, have attested to the fact that the invention indeed works, continually creating a cooling or warming effect that lasts as long as eight hours. Judges from MIT's annual materials-science design competition, who also tried on the device, recently awarded the team first place and a $10,000 prize.

"Buildings right now use an incredible amount of energy just in space heating and cooling. In fact, all together this makes up 16.5 percent of all U.S. primary energy consumption. We wanted to reduce that number, while maintaining individual thermal comfort," co-inventor Sam Shames says in a press release. "We found the best way to do it was local heating and cooling of parts of the body."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While the technology the team has developed appears quite novel, the principle behind it is fairly well documented. Physiologists have known for some time now that the body relies on surface skin on certain spots of the body to detect changes in external temperatures. These areas, called pulse points, are where blood vessels are closest to the skin and signal these sudden shifts to the brain. The neck, for instance, is a pulse point. So are your feet. And that's why the very moment you dip into a swimming pool, it can feel freezing cold.

"Skin, especially certain parts, is extremely sensitive to changes in temperatures. Rather than being consistent, the reading can be overactive to even slight changes," says co-inventor David Cohen-Tanugi. "As an engineer, I'd say it's a bad thermometer."

So, in a sense, what the researchers came up with is a way to kind of hack the body. Instead of putting ice cubes or running cold water on your wrist, as is often suggested, the team put its inquisitive engineering minds together to develop a system that automates the cooling and warming effect through a pattern of pulses that would keep the bracelet wearer comfortable. Cohen-Tanugi compares the wave-like emanations of heat and cold pulses to walking on the beach on a hot summer day and catching a cool breeze and, right when the pleasurable sensation begins to subside, receiving another soothing puff of wind.

"What's really great about it," he says, "is that every time the device went off and on, people still felt surprised each time."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It took fiddling with 15 different prototypes, comprised mostly of parts bought off Amazon, to eventually settle on a version that resembles and feels like a bulky-looking metal wristwatch. Inside, the device features a series of integrated thermometers, finely tuned software controls and sensors to determine the optimal moments, when someone is feeling a bit too hot or cold, to send a pulse or to stop. For now, it relies on a lithium polymer battery, which lasts eight hours before needing a recharge, to power a copper alloy-based heat sink that's capable of producing skin temperature changes of up to 0.4 degrees Celsius per second.

Having "pulses" shooting out of your wristwear might sound unnerving to some people, but Cohen-Tanugi points out that thermoelectric technology has been safely used by consumers for some time. Electric blankets, for example, produce and radiate heat using a similar process. The group at MIT isn't the first to develop a sophisticated product that takes advantage of the "pulse points" principle. One sports apparel company, Mission Athletecare, sells towels, hoodies, and other athletic gear designed with special fabric that can be dipped in water to create a "prolonged cooling effect." And for those who are concerned that tricking the body in this manner may have some serious health consequences, Cohen-Tanugi says it works well, but not that well (nor does it have the potential to ever make heaters or air conditioners obsolete as some media outlets have reported).

"It works best in a moderate environment, like in buildings where for some people the temperature doesn't feel quite right," he says. "But it definitely won't do anything for you when you're in the Sahara desert and need water or when you're in Alaska in the winter."

Ultimately, the team hopes to use the prize money to put something on the market that can be worn all day and sense exactly when you need to be cooled or warmed, as well as make your wrist look good. They're also open to the idea of integrating the technology into so-called smartwatches, which may make the most sense since this latest breed of mobile computers are being heralded as the next big thing. For now, though, Cohen-Tanugi is fine with having the nuts and bolts model to get him through the day.

"Everyone really likes the blast you get from the cooling effect, but personally I like it in warming mode," he adds. "I'm one of those people whose hands get cold in the office."

More from Smithsonian...

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal