9 classic horror stories you can read right now

From Washington Irving to H.P. Lovecraft, a collection of terrifying tales to get you into the Halloween spirit

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1. The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, by Washington Irving (1820)

There's a good chance you read Washington Irving's classic short story in high school. But the surprise success of Fox's new TV series loosely based on the story is a great excuse to go back and reread the original. The story follows the meek Ichabod Crane as he contends with the town bully, Brom Bones, for the hand of Katrina Van Tassel — but an appearance by the legendary Headless Horseman threatens to tip the scales in Brom's favor.

This sequestered glen has long been known by the name of Sleepy Hollow, and its rustic lads are called the Sleepy Hollow Boys throughout all the neighboring country. A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land, and to pervade the very atmosphere. Some say that the place was bewitched by a high German doctor, during the early days of the settlement; others, that an old Indian chief, the prophet or wizard of his tribe, held his powwows there before the country was discovered by Master Hendrick Hudson. Certain it is, the place still continues under the sway of some witching power, that holds a spell over the minds of the good people, causing them to walk in a continual reverie. They are given to all kinds of marvellous beliefs; are subject to trances and visions; and frequently see strange sights, and hear music and voices in the air. The whole neighborhood abounds with local tales, haunted spots, and twilight superstitions: stars shoot and meteors glare oftener across the valley than in any other part of the country, and the nightmare, with her whole nine fold, seems to make it the favorite scene of her gambols.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

2. William Wilson, by Edgar Allan Poe (1839)

There are any number of Edgar Allan Poe short stories that are worthy of this list — feel free to browse them all for yourself — but if I had to choose just one, I'd recommend the underrated William Wilson, in which a man describes a disturbing encounter with his own doppelganger. Poe was so proud of the tale that he sent it to none other than Washington Irving, describing it as his "best effort."

Let me call myself, for the present, William Wilson. The fair page now lying before me need not be sullied with my real appellation. This has been already too much an object for the scorn, for the horror, for the detestation of my race. To the uttermost regions of the globe have not the indignant winds bruited its unparalleled infamy? Oh, outcast of all outcasts most abandoned! To the earth art thou not forever dead? to its honors, to its flowers, to its golden aspirations? and a cloud, dense, dismal, and limitless, does it not hang eternally between thy hopes and heaven?

3. Carmilla, by Sheridan Le Fanu (1872)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Bram Stoker gets a lot of credit for kicking off vampire literature with Dracula, but Sheridan Le Fanu beat him to the punch a full 25 years earlier with the gothic tale Carmilla. The story follows the relationship between two young girls, and modern readers are likely to figure out the so-called "twist" long before it's revealed — but Le Fanu's prose is reliably gorgeous, and the story's lesbian undertones are surprisingly overt for a story of its era.

The first occurrence in my existence, which produced a terrible impression upon my mind, which, in fact, never has been effaced, was one of the very earliest incidents of my life which I can recollect. Some people will think it so trifling that it should not be recorded here. You will see, however, by-and-by, why I mention it. The nursery, as it was called, though I had it all to myself, was a large room in the upper story of the castle, with a steep oak roof. I can't have been more than six years old, when one night I awoke, and looking round the room from my bed, failed to see the nursery maid. Neither was my nurse there; and I thought myself alone. I was not frightened, for I was one of those happy children who are studiously kept in ignorance of ghost stories, of fairy tales, and of all such lore as makes us cover up our heads when the door cracks suddenly, or the flicker of an expiring candle makes the shadow of a bedpost dance upon the wall, nearer to our faces. I was vexed and insulted at finding myself, as I conceived, neglected, and I began to whimper, preparatory to a hearty bout of roaring; when to my surprise, I saw a solemn, but very pretty face looking at me from the side of the bed. It was that of a young lady who was kneeling, with her hands under the coverlet. I looked at her with a kind of pleased wonder, and ceased whimpering. She caressed me with her hands, and lay down beside me on the bed, and drew me towards her, smiling; I felt immediately delightfully soothed, and fell asleep again. I was wakened by a sensation as if two needles ran into my breast very deep at the same moment, and I cried loudly. The lady started back, with her eyes fixed on me, and then slipped down upon the floor, and, as I thought, hid herself under the bed.

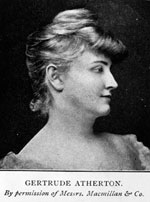

4. The Striding Place, by Gertrude Atherton (1896)

Atherton's brief, dreamlike short story — which has also been published under the titles The Twins and The Bell in the Fog — is set during a grouse-hunting trip in Yorkshire, as a man searches the woods for a friend who disappeared under mysterious circumstances two days earlier. It's never fully clear what has happened, but the story's final two sentences are all the more chilling for their ambiguity.

Weigall did not believe for a moment that Wyatt Gifford was dead, and although it was impossible not to be affected by the general uneasiness, he was disposed to be more angry than frightened. At Cambridge Gifford had been an incorrigible practical joker, and by no means had outgrown the habit; it would be like him to cut across the country in his evening clothes, board a cattle-train, and amuse himself touching up the picture of the sensation in West Riding.

5. The Turn of the Screw, by Henry James (1898)

There's nothing like a twisty ghost story — and Henry James established himself as one of the standard-bearers with this legendary tale about a governess who becomes convinced that she and her charges are being stalked by ghosts. The story's limited perspective creates a sense of unreliability that continues to fuel debate among fans and critics more than a century after its original publication.

The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve in an old house, a strange tale should essentially be, I remember no comment uttered till somebody happened to say that it was the only case he had met in which such a visitation had fallen on a child. The case, I may mention, was that of an apparition in just such an old house as had gathered us for the occasion — an appearance, of a dreadful kind, to a little boy sleeping in the room with his mother and waking her up in the terror of it; waking her not to dissipate his dread and soothe him to sleep again, but to encounter also, herself, before she had succeeded in doing so, the same sight that had shaken him. It was this observation that drew from Douglas — not immediately, but later in the evening — a reply that had the interesting consequence to which I call attention. Someone else told a story not particularly effective, which I saw he was not following. This I took for a sign that he had himself something to produce and that we should only have to wait. We waited in fact till two nights later; but that same evening, before we scattered, he brought out what was in his mind.

6. The Monkey's Paw, by W.W. Jacobs (1902)

You've probably seen one of the countless parodies of The Monkey's Paw on film or TV, but have you ever read the original story? The twisty narrative follows a couple who receive a monkey's paw that grants them three wishes — but everything they ask for comes with a horrible unintended consequence.

Without, the night was cold and wet, but in the small parlour of Laburnum villa the blinds were drawn and the fire burned brightly. Father and son were at chess; the former, who possessed ideas about the game involving radical chances, putting his king into such sharp and unnecessary perils that it even provoked comment from the white-haired old lady knitting placidly by the fire.

"Hark at the wind," said Mr. White, who, having seen a fatal mistake after it was too late, was amiably desirous of preventing his son from seeing it.

7. The Willows, by Algernon Blackwood (1907)

Algernon Blackwood has fallen into relative obscurity outside horror circles — but he's long overdue for a revival. His strongest story, The Willows, is a moody and ominous story about two friends who end up stranded alone on a riverbank during a canoe trip on the Danube. The Willows' creeping sense of dread is almost unmatched in horror fiction. (At several points during his lifetime, H.P. Lovecraft wrote that he considered it the greatest supernatural story of all time).

After leaving Vienna, and long before you come to Budapest, the Danube enters a region of singular loneliness and desolation, where its waters spread away on all sides regardless of a main channel, and the country becomes a swamp for miles upon miles, covered by a vast sea of low willow-bushes. On the big maps this deserted area is painted in a fluffy blue, growing fainter in color as it leaves the banks, and across it may be seen in large straggling letters the word Sumpfe, meaning marshes.

In high flood this great acreage of sand, shingle-beds, and willow-grown islands is almost topped by the water, but in normal seasons the bushes bend and rustle in the free winds, showing their silver leaves to the sunshine in an ever-moving plain of bewildering beauty. These willows never attain to the dignity of trees; they have no rigid trunks; they remain humble bushes, with rounded tops and soft outline, swaying on slender stems that answer to the least pressure of the wind; supple as grasses, and so continually shifting that they somehow give the impression that the entire plain is moving and alive. For the wind sends waves rising and falling over the whole surface, waves of leaves instead of waves of water, green swells like the sea, too, until the branches turn and lift, and then silvery white as their underside turns to the sun.

8. The Outsider, by H.P. Lovecraft (1926)

Like Poe, Lovecraft's canon is so rich that you'd be better off browsing a list of his public domain short stories or just picking up a full short-story collection. But if you're looking to dip your toe into the water, I'd suggest The Outsider — a strange, beautifully written tale about a man who finally escapes a dank castle where he has spent his entire life in isolation. It's one of Lovecraft's shortest stories, but also one of his most effective.

Unhappy is he to whom the memories of childhood bring only fear and sadness. Wretched is he who looks back upon lone hours in vast and dismal chambers with brown hangings and maddening rows of antique books, or upon awed watches in twilight groves of grotesque, gigantic, and vine-encumbered trees that silently wave twisted branches far aloft. Such a lot the gods gave to me — to me, the dazed, the disappointed; the barren, the broken. And yet I am strangely content, and cling desperately to those sere memories, when my mind momentarily threatens to reach beyond to the other.

9. The Pale Man, by Julius Long (1934)

Most of the stories on this list are acknowledged classics, but The Pale Man, which was published in a 1934 issues of the horror magazine Weird Tales, is a snappy obscurity that was rescued by the people at Wikisource. A man living in a small country hotel becomes obsessed with the only other permanent resident — a a strange pale man who inexplicably moves from room to room. It's an eerie and extremely brief tale that can be consumed in less than 10 minutes — the perfect story for anyone looking for a quick way to get into the Halloween spirit.

I have not yet met the man in No. 212. I do not even know his name. He never patronizes the hotel restaurant, and he does not use the lobby. On the three occasions when we passed each other by, we did not speak, although we nodded in a semi-cordial, noncommittal way. I should like very much to make his acquaintance. It is lonesome in this dreary place. With the exception of the aged lady down the corridor, the only permanent guests are the man in No. 212 and myself. However, I should not complain, for this utter quiet is precisely what the doctor prescribed.

I wonder if the man in No. 212, too, has come here for a rest. He is so very pale. Yet I can not believe that he is ill, for his paleness is not of a sickly cast, but rather wholesome in its ivory clarity. His carriage is that of a man enjoying the best of health. He is tall and straight. He walks erectly and with a brisk, athletic stride. His pallor is no doubt congenital, else he would quickly tan under this burning, summer sun.

Looking for even more terrifying fiction for Halloween? Here are nine contemporary horror stories you can read right now.

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day