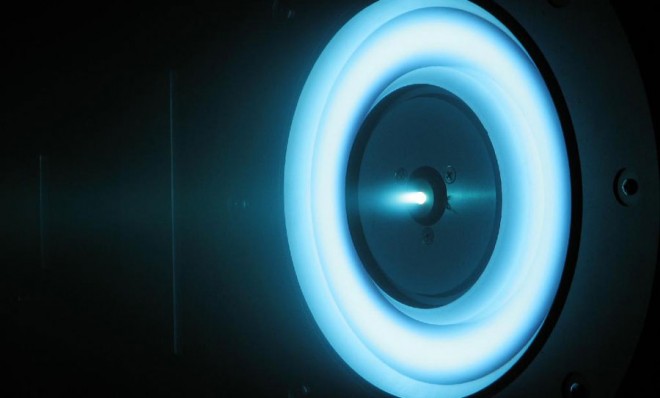

Take a look at NASA's new solar-powered ion propulsion engine

Ain't it pretty?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If we're ever going to explore the universe's far corners in cool spaceships that look like giant pizza cutters, we're first going to need more efficient engines. On Tuesday, NASA took the wraps off a potential next-gen thruster system that looks like something described in Trekkie fanfic: A solar-electric ion propulsion engine.

The propulsion system of tomorrow, in this instance, will be powered by inert and odorless xenon gas, which gives the engine its blue-ish glow. The physics of how the whole thing works can get pretty complicated, but essentially the ion thruster system operates by combining (1) high-energy, negatively charged electrons together with (2) neutral propellant atoms (xenon gas) in a contained environment. A free-for-all party chamber, if you will.

The hope is that in this chaotic little engine recess (which is actually quite efficient relative to today's standards), the electrons and atoms will slam into one another like bumper cars. These mini-collisions yield a second electron, and boom: Thrust is generated. NASA explains:

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Since the ions are generated in a region of high positive and the accelerator grid's potential is negative, the ions are attracted toward the accelerator grid and are focused out of the discharge chamber through the apertures, creating thousands of ion jets. The stream of all the ion jets together is called the ion beam. The thrust force is the force that exists between the upstream ions and the accelerator grid. The exhaust velocity of the ions in the beam is based on the voltage applied to the optics. [NASA]

NASA researchers claim the voltage can be applied by any kind of electricity source, but will most likely be some combination of nuclear and solar energy. Mashable notes that NASA is considering the propulsion system for the agency's asteroid retrieval program, which will send a remote unmanned spacecraft out to nab a nearby asteroid and park it within a moon's orbit to study — a mini moon for the moon.

Usually depicted as the spaceship engine of choice by science fiction writers, the ion propulsion system's "efficient use of fuel and electrical power enable modern spacecraft to travel farther, faster, and cheaper than any other propulsion technology currently available," NASA's scientists and engineers say. Still, while it's vastly more efficient than today's thruster systems, the engine is still a far cry from the ultra-fast warp drives dreamed up by the likes of Gene Roddenberry.

Which isn't to say ultra-fast space travel won't be possible within a few decades: A 2010 NASA report hints that the space agency has been looking into potential ways to produce nuclear fusion reactions with beams of — get this — antimatter. Sadly, though, such a salivating power alternative probably won't be available anytime within the next 40 years. "But 50, 60?" Jason Hay, a senior aerospace technology analyst for consulting firm The Tauri Group, asks at Space.com. "Quite possible, and something that would have a significant impact on exploration by changing the mass-power-finance calculus when planning."

To infinity and beyond, y'all.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com