The Russian satellite destroyed by garbage

Space junk strikes again

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A few hundreds kilometers outside of Earth's atmosphere is something called the LEO zone, or low-Earth orbit. A stepping stone to the stars, this area is home to hundreds of billions of dollars worth of space equipment — everything from the International Space Station to the Hubble Space Telescope.

But over the last few years, the LEO zone has gotten increasingly messy, littered with fragments from dispatched rockets and deactivated satellites. Astronomers affectionately refer to this debris as space junk. But even the tiniest scrap can inflict tremendous damage.

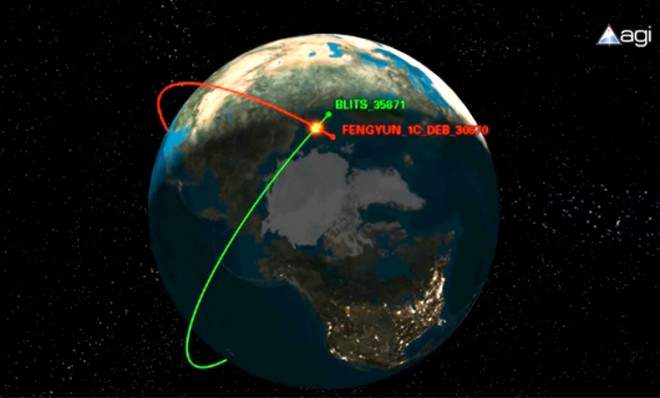

Space.com reports that earlier this year, Russia's Ball Lens In The Space (BLITS) mini-satellite collided with a piece of debris that broke off from a 2007 Chinese anti-satellite test. The crash rendered Russia's spherical lens little more than a giant paperweight.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

BLITS isn't the first piece of space equipment destroyed by indiscriminate debris — similar accidents occurred in 1996, 2007, and 2009. And, as space watchers caution, it surely won't be the last, either.

"Many satellites in LEO are having to maneuver on a regular basis to avoid threatening close approaches with debris," Brian Weeden, an adviser to the Secure World Foundation, told Space.com in an email. "This is just one more data point that shatters the myth of the 'big sky' theory regarding space activities and shows that debris is one of the most pressing threats satellite operators in LEO have to contend with."

According to NASA, there are more than 21,000 pieces of orbital debris larger than 10 cm (about the size of a baseball) flying around the sky, and 500,000 between 1 and 10 cm. These pieces can whiz by at speeds up to 17,500 mph, meaning that even tiny chunks are dangerous; a small fleck of paint, for example, can do serious damage to a passing spacecraft, which, of course, puts astronaut lives at risk.

Last October, in a widely reported case, the ISS — which is covered in protective armor — was forced to swerve to avoid a potential collision with a dangerous chunk of space debris. Six astronauts, including two Americans, were onboard at the time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So what's being done to fix our collective mess? NASA does its best to track pieces larger than 10 cm with the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, which uses ground-based radar to paint a roadmap. And for what it's worth, there are all sorts of outlandish proposals to destroy the debris, from Earth-based lasers to probes that drag the junk back into our atmosphere, where it incinerates on re-entry. (Unfortunately, most of these "ideas" are exactly that.)

When it comes down to it, no one wants to play space janitor. According to some estimates, 29 percent of the junk is American, 37 percent is Russian, and 28 percent is Chinese. Add in the fact that cleanup is expensive — one project for a "Space Fence" proposed by the U.S. Air Force would cost approximately $1 billion — and we're left with governments that would rather turn a blind eye than foot the bill.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day