Google says the FBI is spying on some of you

And it's perfectly legal

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For millions of Americans, Google is the fabric that weaves the various threads of our digital lives together: Gmail, Gchat, Google Voice, search queries, YouTube, Maps, Chrome — you name it. So it shouldn't really come as a surprise that the Federal Bureau of Investigation has repeatedly tapped the tech company for otherwise-private information concerning a small percentage of Google's users.

But let's put it more plainly: The FBI has been spying on some of you.

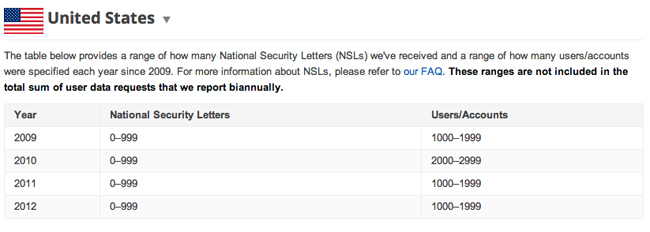

In a new Transparency Report announced in an official blog post, Google has released previously unseen information about the number of National Security Letters (NSLs) it has received from the FBI in the past couple of years. According to Wired, these letters "allow the government to get detailed information on Americans' finances and communications without oversight from a judge." Needless to say, the FBI sends NSLs out all the time — hundreds of thousands of them, in fact — to internet service providers, banks, credit companies, and other businesses. Unsurprisingly, organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union have accused the FBI of abusing the letters' power post-9/11.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Until recently, it's been unlawful for a company to disclose when it has received an NSL. Now, thanks to a new deal with the Obama administration, Google is able to publish a broad range of instances in which it has received such FBI requests.

As you can see, Google says it receives between 0 and 999 NSLs from the government each year. In 2009, those letters contained requests asking for information concerning between 1,000 and 1,999 users/accounts. In 2010, the FBI was slightly busier — 2,000 to 2,999 different users/accounts were requested. Then in 2011 and 2012, that range dipped back down.

The search giant doesn't comply with every NSL it receives, and claims to carefully vet each request. "We review it carefully and only provide information within the scope and authority of the request," writes Google. "We may refuse to produce information or try to narrow the request in some cases." Google also says that the standard practice is to notify users when an NSL has been received concerning them, although the FBI has the power to nullify the disclosure if it may result in "a danger to the national security of the United States, interference with a criminal, counterterrorism, or counterintelligence investigation, interference with diplomatic relations, or danger to the life or physical safety of any person."

You can read Google's Transparency Report for yourself here.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And it's worth remembering: The FBI and other government agencies can still access your email without a warrant as long as the information has been stored on a third-party server for 180 days or more (per a convoluted and terribly antiquated 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act). A new email and phone tracking bill introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives yesterday seeks to make it harder for authorities to snoop around without a judge's order.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix