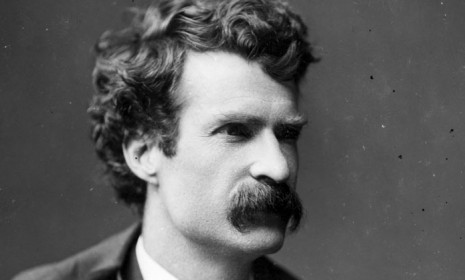

Close encounters with Mark Twain

In Rudyard Kipling, says Craig Brown, Twain found an admirer. In Helen Keller, he felt the presence of God

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

IN 1889, RUDYARD KIPLING is 23 years old, though he looks closer to 40. He arrives in San Francisco on May 28, after a 20-day voyage from Japan. He is greedy for life. He witnesses a gunfight in Chinatown, lands a 12-pound salmon in Oregon, meets cowboys in Montana, is appalled by Chicago, and falls in love with his future wife in Beaver, north Pennsylvania.

Before he leaves the United States, he is determined to meet his hero, Mark Twain. He goes on a wild-goose chase—to Buffalo, then Toronto, then Boston—before tracking him down to Elmira, N.Y., in June, where a policeman tells him he spotted Twain, "or someone very like him," driving a buggy through town the day before. "He lives out yonder at East Hill, three miles from here."

At East Hill, he is informed that Twain is downtown, at the home of his brother-in-law, Gen. Charles J. Langdon. He finds the house and rings the doorbell, but then has second thoughts. "It occurred to me for the first time that Mark Twain might possibly have other engagements than the entertainment of escaped lunatics from India."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

He is led into a big, dark drawing room. There, in a huge chair, he finds the 53-year-old author of Tom Sawyer with "a mane of grizzled hair, a brown mustache covering a mouth as delicate as a woman's, a strong, square hand shaking mine, and the slowest, calmest, levelest voice in all the world…I was shaking his hand. I was smoking his cigar, and I was hearing him talk—this man I had learned to love and admire 14,000 miles away."

Kipling is transfixed. "That was a moment to be remembered; the landing of a 12-pound salmon was nothing to it. I had hooked Mark Twain, and he was treating me as though under certain circumstances I might be an equal."

The two men discuss the difficulties of copyright before moving on to Twain's work. "Growing bold, and feeling that I had a few hundred thousand folk at my back, I demanded whether Tom Sawyer married Judge Thatcher's daughter and whether we were ever going to hear of Tom Sawyer as a man."

Twain gets up, fills his pipe, and paces the room in his bedroom slippers. "I haven't decided. I have a notion of writing the sequel to Tom Sawyer in two ways. In one I would make him rise to great honor and go to Congress, and in the other I should hang him. Then the friends and enemies of the book could take their choice."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Kipling raises a voice of protest: To him, Tom Sawyer is real.

"Oh, he is real," says Twain. "He's all the boys that I have known or recollect; but that would be a good way of ending the book, because, when you come to think of it, neither religion, training, nor education avails anything against the force of circumstances that drive a man. Suppose we took the next four and 20 years of Tom Sawyer's life, and gave a little joggle to the circumstances that controlled him. He would, logically and according to the joggle, turn out a rip or an angel."

Twain laughs. They move on to autobiography. "I believe it is impossible for a man to tell the truth about himself or to avoid impressing the reader with the truth about himself," Twain says. "I made an experiment once. I got a friend of mine—a man painfully given to speak the truth on all occasions, a man who wouldn't dream of telling a lie—and I made him write his autobiography for his own amusement and mine…good, honest man that he was, in every single detail of his life that I knew about he turned out, on paper, a formidable liar. He could not help himself."

TWAIN TALKS OF the books he likes to read. "I never cared for fiction or storybooks. What I like to read about are facts and statistics of any kind. If they are only facts about the raising of radishes, they interest me. Just now, for instance, before you came in, I was reading an article about mathematics. Perfectly pure mathematics. My own knowledge of mathematics stops at 12 times 12, but I enjoyed that article immensely. I didn't understand a word of it; but facts, or what a man believes to be facts, are always delightful."

After two hours, the interview comes to an end. The great man, who never minds talking, assures his disciple that he has not interrupted him in the least.

Seventeen years on, Rudyard Kipling is world famous. Twain grows nostalgic for the time he spent in his company. "I believe that he knew more than any person I had met before, and he knew I knew less than any person he had met before.… When he was gone, Mr. Langdon wanted to know about my visitor. I said, 'He is a stranger to me but is a most remarkable man—and I am the other one. Between us, we cover all knowledge; he knows all that can be known, and I know the rest.'"

Twain, now age 70, is addicted to Kipling's works. He rereads Kim every year, "and in this way I go back to India without fatigue.… I am not acquainted with my own books, but I know Kipling's books. They never grow pale to me; they keep their color; they are always fresh."

The worshipped has become the worshipper.

AS HELEN KELLER'S carriage draws up between the huge granite pillars of Mark Twain's house in Stormfield, Conn., the most venerable author in America is there to greet her, though she can neither see him nor hear him. Her companion Annie Sullivan—her eyes and ears—tells Helen that he is all in white, his beautiful white hair glistening in the afternoon sunshine "like the snow spray on gray stones."

It is February 1909. Twain and Keller first met 15 years ago, when he was 58 and she was just 14. Struck deaf and blind by meningitis at the age of 18 months, Helen had, through sheer force of will, discovered a way to communicate: She finds out what people are saying by placing her fingers on their lips, throat, and nose, or by having Annie transpose it onto the palm of her hand in letters of the alphabet.

Taken up as a prodigy by the great and the good, she formed a special friendship with Twain. "The instant I clasped his hand in mine, I knew that he was my friend. He made me laugh and feel thoroughly happy by telling some good stories, which I read from his lips.… He knew with keen and sure intuition many things about me and how it felt to be blind and not to keep up with the swift ones—things that others learned slowly or not at all. He never embarrassed me by saying how terrible it is not to see, or how dull life must be, lived always in the dark."

Unlike other people, Twain never patronized her. "He never made me feel that my opinions were worthless, as so many people do. He knew that we do not think with eyes and ears, and that our capacity for thought is not measured by five senses. He kept me always in mind while he talked, and he treated me like a competent human being. That is why I loved him."

For his part, Twain is in awe. "She is fellow to Caesar, Alexander, Napoleon, Homer, Shakespeare, and the rest of the immortals. She will be as famous a thousand years from now as she is today." Shortly after their first meeting, Twain formed a circle to fund her education at Radcliffe College, which led to her publishing an autobiography at the age of 22, which in turn led her to become almost as celebrated as Twain himself.

But the intervening years have struck Twain some heavy blows. One of his daughters, Susy, has died of meningitis, another of an epileptic fit in a bathtub, and his wife, Livy, has died of heart disease. Throughout Helen's stay he acts his familiar bluff, entertaining old self, but she senses the deep sadness within.

"There was about him the air of one who had suffered greatly. Whenever I touched his face, his expression was sad, even when he was telling a funny story. He smiled, not with the mouth but with his mind—a gesture of the soul rather than of the face."

BUT FOR THE moment, he welcomes them into the house for tea and buttered toast by the fire. Then he shows them around. They go upstairs to see his bedroom. "Try to picture, Helen, what we are seeing out of these windows. We are high up on a snow-covered hill. Beyond are dense spruce and fir woods, other snow-clad hills, and stone walls intersecting the landscape everywhere, and, over all, the white wizardry of winter. It is a delight, this wild, free, fir-scented place."

He shows the two women to their suite. On the mantelpiece there is a card telling burglars where to find everything of value. There has recently been a burglary, Twain explains, and this notice will ensure that any future intruders do not bother to disturb him.

Over dinner, Twain holds forth, "his talk fragrant with tobacco and flamboyant with profanity."

Dinner comes to an end, but "his talk continues around the fire," says Helen. "He seemed to have absorbed all America into himself. The great Mississippi River seemed forever flowing, flowing through his speech, through the shadowless white sands of thought. His voice seemed to say, like the river, 'Why hurry? Eternity is long; the ocean can wait.'"

Before Helen leaves Stormfield, Twain is more solemn. "I am very lonely, sometimes, when I sit by the fire after my friends have departed. My thoughts trail away into the past. I think of Livy and Susy and I seem to be fumbling in the dark folds of confused dreams."

As she says goodbye, Helen wonders if they will ever meet again. Once more, her intuition proves right. Twain dies the following year. Some time later, Helen returns to where the old house once stood; it has burned down, with only a charred chimney still standing. She turns her unseeing eyes to the view he once described to her, and at that moment feels someone coming toward her. "I reached out, and a red geranium blossom met my touch. The leaves of the plant were covered with ashes, and even the sturdy stalk had been partly broken off by a chip of falling plaster. But there was the bright flower smiling at me out of the ashes. I thought it said to me, 'Please don't grieve.'"

She plants the geranium in a sunny corner of her garden. "It always seems to say the same thing to me, 'Please don't grieve.' But I grieve, nevertheless."

From Hello Goodbye Hello, by Craig Brown. ©2011 by Craig Brown. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.