Did cavemen have dentists?

Researchers find a 6,500-year-old tooth with an awful cavity — that someone had stuffed with a primitive beeswax filling to ease the pain

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cavities can be excruciating, and new evidence suggests that prehistoric man used a surprisingly sophisticated technique to deal with the pain: Dental fillings. A team of scientists in Italy has identified a 6,500-year-old cracked tooth repaired with beeswax, suggesting that our early ancestors knew a thing or two about dental work. A closer look at the findings:

What did researchers find?

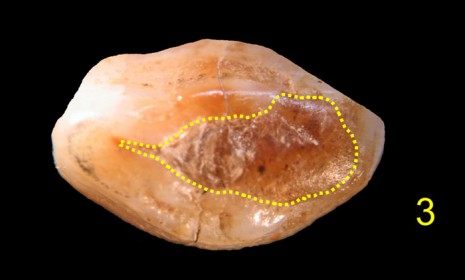

The study, outlined in the journal PLoS One, takes a look at a fossilized jawbone discovered in Slovenia near Trieste. Of special interest was the left canine, which sported a large crack that "exposed some of the inner enamel and tissues within the tooth called dentin," says Brian Fung at The Atlantic. In other words: It probably caused a lot of pain.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And it was repaired with beeswax?

Yes. Infrared spectroscopy confirmed the ancient filling to be beeswax, while radiocarbon dating found that it was about 6,500 years old. In all likelihood, the procedure was done either shortly before or after the 24- to 30-year-old individual's death. The team could not rule out the possibility that the wax was "added during a funerary ritual," says Rossella Lorenzi at Discovery News, although evidence suggests that it was added while the young man was still alive.

Why do they think that?

The severity of the crack has researchers believing the tooth was incredibly sensitive, and probably caused him a lot of discomfort. For example, other teeth had exposed dentin, yet no beeswax was applied. That means that if the dental work was done when he was still alive, they write, "the intervention was likely aimed to relieve tooth sensitivity derived from either exposed dentin... or the pain resulting from chewing on a cracked tooth." Essentially, it's the oldest "therapeutic-palliative dental filling" found to date.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Was the cavity caused by eating bad food?

Probably not. The "severe wear and tear" on the tooth was probably due to other activities, says Charles Choi at LiveScience. Men, for instance, regularly used their teeth to soften leather or to help make tools. "At the moment, we do not have any idea if this is an isolated case or if similar interventions were quite widespread in Neolithic Europe," researcher Federico Bernardini tells LiveScience. The next project for the team will be to figure out how widespread this type of dental practice really was.

Sources: The Atlantic, Discovery News, LiveScience, Medical News Today

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day