Why giving Syrian refugees safe zones is easier said than done

Turkey, afraid of being overwhelmed by the exodus from Syria, wants help setting up havens within the war-ravaged country... but it doesn't have many takers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

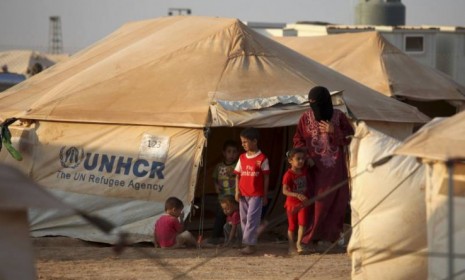

With escalating violence triggering a sharp rise in the flow of refugees out of Syria, Turkey this week called on other nations to help establish safe zones to allow displaced civilians to stay within their own country. Turkey and Jordan are shouldering most of the burden of sheltering the 170,000 men, women, and children the United Nations estimates have flooded out of Syria during its 18-month uprising. "We expect the U.N. to step in," says Ahmet Davutoglu, Turkey's foreign minister. "No one has the right to expect Turkey to take on this international responsibility on its own." The idea of establishing protected havens for Syrian civilians has been floating for months, but so far nothing has been done. It seems like a humanitarian no-brainer — why is it so complicated to get it done? Here, a brief guide:

How bad is the refugee crisis?

It's bad, and getting worse fast. Two dozen Jordanian police officers were wounded Tuesday when riots broke out to protest conditions at Jordan's Zaatari Camp, a parched desert tent city that is plagued by dust storms and snakes, and houses 21,000 refugees. With fighting between Syrian government forces and rebels growing more intense — including some of the deadliest government airstrikes yet on civilian neighborhoods in Aleppo and Deraa province — the influx into Jordan went from 4,500 last week to 10,200 over the past several days. U.N. officials estimate that the number escaping to Turkey has jumped to 5,000 a day from just 400 or 500 a day a few weeks ago.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What does Turkey want to do?

It says it can handle 100,000 refugees — it's already housing 80,000 — but the U.N. High Commission for Refugees says the number could climb as high as 200,000 if left unchecked. There are, after all, more than 1 million displaced civilians still inside Syria, according to some estimates. To keep the exodus from growing too large to handle, and to give displaced civilians haven without leaving Syria, Ankara has drawn up plans for enforcing a buffer zone 12 miles inside the Syrian border. France has endorsed the plan, but other countries are dragging their feet.

Why is the international community slow to act?

The main reason is that keeping a "safe zone" safe requires soldiers, and nobody wants to send them. Turkey is appealing to the U.N. Security Council for help, but Russia and China are expected to veto any efforts to get the U.N. involved. If rebel fighters try to provide protection, the proposed buffer area could become an easy target for government forces. The U.S. and other countries have little appetite for taking on the job — in part because establishing a humanitarian corridor where refugees would truly be safe would require huge supply effort and a Libya-style "no-fly" zone, which would mean even greater international involvement — tantamount to a full-fledged military intervention.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But wouldn't a show of force be enough?

Maybe. But nobody can stomach the thought of a repeat of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre of 8,000 Muslim men and boys by Bosnian Serbs in what the U.N. had declared a protected area. Whoever's asked to provide security would have to do "whatever it takes," says Ariel Zirulnick at The Christian Science Monitor, and that's a "slippery slope" that could draw them deeper into the rebels' fight against Assad. That might explain Assad's confidence that Turkey's proposal for a buffer zone was "not practical," and won't happen no matter how "hostile" other countries are to his regime.

Sources: ABC News, The Associated Press, The Christian Science Monitor, Reuters, The Telegraph

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day