The 5 best non-fiction books of 2011

As the year draws to a close, critics honor histories of the global economic collapse, the perils of Nazi Germany, and the late, great Steve Jobs

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

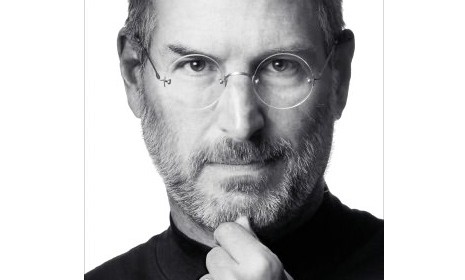

1. Steve Jobs

by Walter Isaacson

(Simon & Schuster, $35)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Steve Jobs was both brilliant and a "complicated, peculiar personality," said Michael S. Rosenwald in The Washington Post. Granted full access to the Apple CEO during his last months, Walter Isaacson this fall put the finishing touches on a comprehensive biography that gives us a Jobs who's "charming, loathsome, lovable, obsessive, maddening." Isaacson "clearly admires" his subject — crediting the late business innovator with revolutionizing how we interact with technology and "putting him in a league with Thomas Edison and Henry Ford." Yet the veteran author doesn't hesitate to throw light on Jobs's boorishness. Isaacson's finely detailed portrait in fact never manages to truly reconcile "Bad Steve and Good Steve," said Casey Common in the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Still, the former Time editor understands the power to inspire that was crucial to Jobs's success. "When he gave people seemingly impossible tasks, it was often with the message: 'You can do this.' Often, to their own surprise, they could."

A caveat: Isaacson tends to oversell his arguments, and he writes in a "dutiful, lumbering journalese," said Sam Leith in the London Guardian.

2. In the Garden of Beasts

by Erik Larson

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(Crown, $26)

"How do we know implacable evil when we see it?" asked Mary Ann Gwinn in The Seattle Times. Erik Larson's "eerie and disturbing" book re-creates the inadequate response of one American family who had an early chance to confront the Nazi threat. William Dodd, the U.S. ambassador to Germany from 1933 to 1937, believed naïvely that he could provide a moderate voice in Adolf Hitler's ear. But if Dodd was naïve, his daughter, Martha, was "oblivious," carrying on affairs indiscriminately with various Nazi officers. The increasing persecution of Jews and the 1934 political purge known as the Night of the Long Knives finally brought the Dodds to their senses, said Jeff Bailey in the Orlando Sentinel. "As the events leading up to World War II go," the U.S. ambassador's too-slow transformation into an alarm-ringer may rank "pretty low in importance." But Larson turns this historical sideshow into "a terrific storytelling vehicle," giving us an inside feel for a troubled Berlin.

A caveat: It's a little hard to warm up to the hapless Dodd and his "feckless, flirtatious daughter," said Gwinn.

3. Boomerang

by Michael Lewis

(Norton, $26)

Michael Lewis can make "virtually any subject both lucid and compelling," said Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times. Lewis's travelogue on the hot spots of the recent global economic collapse offers a clear analysis of the financial chicanery and irresponsibility that produced economic crises in places like Greece, Iceland, Ireland, and here at home. He makes topics like sovereign debt "not only comprehensible but fascinating," even to those who don't regularly read the business pages. America, "it turns out," was not the only nation behaving badly in the 1990s and beyond, said Chuck Leddy in The Boston Globe. In Greece, paying taxes seemed to have been regarded as optional. In Ireland, the inbred pessimism of the culture was overwhelmed by an unsustainable housing boom. For every stop, Lewis has a few tales of human greed and misdeed, and all point to the possibility that the current mess is "not just a problem of public deficits but of moral deficits."

A caveat: Lewis builds much of his analysis on odd or ugly cultural stereotypes, said Carlos Lozada in The Washington Post. "It's not a pretty sight."

4. Blue Nights

by Joan Didion

(Knopf, $25)

"Joan Didion seems to think she's entering her final act," said Nathan Heller in Slate.com. If so, she's making a strong finish. Blue Nights is Didion's "haunting" attempt to share the pain she experienced upon losing her daughter, Quintana, less than two years after the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. But this isn't just a grief memoir. Didion uses Quintana's death as a jumping-off point to explore her own failures and late-life anxieties. In doing so, she "lets us see something readers aren't often allowed to see: a writer calling her own choices into question, a relentless cultural critic turning an unsqueamish eye on her own life." The book is a "devastating companion volume to The Year of Magical Thinking," Didion's 2005 memoir about Dunne's death, said Heller McAlpin in The Washington Post. "The marvel of Blue Nights is that its 76-year-old, matchstick-frail author has found the strength to articulate her deepest fears — which are fears we can all relate to."

A caveat: Didion comes across as a snob, as "consumed with high-end brand names" and name-dropping as with her personal losses, said Evelyn Theiss in the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

5. Pulphead

by John Jeremiah Sullivan

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $16)

John Jeremiah Sullivan might be "the best essayist of his generation," said Lev Grossman in Time. In the pieces collected here, the 30-something Kentucky native handles a range of assignments — covering a Christian rock festival, musing on the strange career of Axl Rose, hanging out with the cast of MTV's The Real World. In every setting, he proves to be possibly "the closest thing we have right now to Tom Wolfe, and that includes Tom Wolfe." Then again, the "better comparison" might be to the late David Foster Wallace. Sullivan is in fact "kinder than the former, and less neurotic than the latter," said James Wood in The New Yorker. What he shares with Wolfe and Wallace are "a very good eye," an ironic tone, and a gift for poignant anecdotes that "fly off the wheels of his larger narratives." Yet he's distinguished by his ability to avoid condescension. Sullivan is "a writer interested in human stories" — a patient listener "hospitable to otherness."

A caveat: Sullivan is not superhuman, said Kristofer Collins in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. "Even he cannot wring pathos from doing Jell-O shots" with the cast of The Real World.

How the books were chosen

Rankings are based on end-of-year recommendations published by The Atlantic, CSMonitor.com, GQ, The Kansas City Star, Minneapolis Star Tribune, The New York Times, The New Yorker, NPR​.org, Publishers Weekly, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Salon.com, The Seattle Times, Slate.com, Time, and The Washington Post.