Uttar Pradesh: from a once-in-a-generation festival to tiger tracking in an ancient forest

Soak up the state's rich culture on one of Explorations Company's specially curated tours

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's really only one way to arrive at the largest religious gathering on planet earth: on the back of a motorcycle.

Our mode of transport wasn't a matter of arriving in style (although there was a cinematic feel to it) but pure necessity. Some 660 million pilgrims journeyed to the banks of the River Ganges over 44 days during Kumbh Mela, the religious Hindu festival we had come to witness – although as we moved with the swirling currents of an almost endless sea of ox carts, motorcycles and pilgrims on foot, it seemed like everyone had arrived all at once.

Some 660 million pilgrims make the journey to the River Ganges

Witnessing the world's largest pilgrimage

In fact, our arrival at the festival coincided with another sacred day, the Maha Shivratri Festival. Over 15 million people came to bathe on this day alone.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Witnessing the sheer number of people moving to and from the Ganges during the festival is almost incomprehensible. And a surprisingly efficient cottage industry of "mototaxis" springs up each year: for a fee, young men ferry pilgrims on the backs of their motorcycles. To say the least, it's a white-knuckle ride, but it's also likely to be the most jaw-dropping journey you ever take.

It's only really possible to take in a few impressions as you dart through the crowds to the river bank: ash-covered sadhus sitting silently by the road, a rainbow of saris flashing past, entire families crammed impossibly into three-wheeled tuktuks, and all accompanied by a ceaseless background of devotional chants and traffic horns. All who travelled there had one shared goal: to bathe in the Ganges and cleanse themselves of sin.

A full Kumbh Mela is held every 12 years, when planetary alignments dictate that the Ganges is at its most potent for spiritual purification. Each gathering draws hundreds of millions, but this year carried a particular weight. We had arrived for the Maha Kumbh, a rare celestial event occurring only once every 144 years, making this festival a truly once-in-a-generation event.

My travelling companions and I mused that the scale of the festival on just the one day we visited was like over 350 Glastonbury Festivals occurring at once – although of course, it is almost nothing like the carefully planned revelry which happens on Worthy Farm.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The religious event at the River Ganges is said to cleanse visitors of sin

Bidding farewell to our mototaxis, we ventured further to the bank of the Ganges, where, after some skilful negotiations from our guides, we were allowed onto a small wooden barge and rowed up the river. The most sacred spot to bathe is at the Triveni Sangam, where the Ganges, the Yamuna and the Sarasvati (a mythical river said to run under the Ganges) meet.

I was about to ask our guide where exactly this spot is, when it became clear there was no need: the floating mass in the distance was a small island made of countless numbers of the same wooden barges, which pilgrims would jump off into the water (which I was surprised to find was only waist-deep) and – as hundreds of millions of other Hindus also had done – take part in the sacred ritual bathing.

The most sacred spot to bathe in is at the Triveni Sangam

Uttar Pradesh's overlooked capital

After 24 frenetic hours at Kumbh Mela, we travelled from Prayagraj to Lucknow, a place offering as close to respite as any major Indian city can. Uttar Pradesh's sometimes overlooked capital carries a deep cultural heritage from its storied rulers – the Mughals, Nawabs, and the British. It is a city that brims with architectural marvels like the Bara Imambara, an awe-inspiring 18th-century mosque and meeting place, said to contain more than 1,000 passages and 489 doorways.

The city is equally famous for chikankari, the exquisitely delicate floral embroidery produced only here. This intricate handmade craft, refined under Awadh court patronage in the 18th and 19th centuries, was woven into Mughal court dress.

Here we were invited to dine at the ancestral home of academic and poet Ali Mahmudabad. Mahmudabad House is a striking example of Indo-European Regency architecture. Mahmudabad explained the home had been preserved with this philosophy in mind: "Rebuild what is necessary and retain what is beautiful."

That evening, a candlelit concert unfolded on the rooftop courtyard of the great house. And as the haunting Yaman raga emerged from the sarangi, accompanied by table drums, the music brought to mind the words of T.S. Eliot: "a music heard so deeply/That it is not heard at all, but you are the music/While the music lasts".

From there, we descended to the spectacular dining room, where portraits of past inhabitants gazed down and an ancient stuffed tiger's head watched over proceedings from the mantelpiece. Renowned chef and food writer Taiyaba Ali had prepared a 12-course feast of Awadhi cuisine that any Michelin-starred kitchen would struggle to replicate; any true foodie must eat here.

Dudhwa: Uttar Pradesh's hidden wilderness

The jewel of this region, however, is undoubtedly the lush Terai woodlands and wetlands found in Dudhwa National Park. It is one of India's "least-explored wildernesses", explains Chinmay Vasavada of the Explorations Company, the careful curator behind our trip, who marvelled at the forest's "almost Kipling-esque magic".

Based at the stunning Jaagir Manor, a boutique luxury hotel in the heart of this breathtaking landscape, we searched for tigers under the guidance of Amit Bhangre, the lodge's general manager and passionate naturalist. His deep connection to nature is evident – when asked his favourite type of music one evening, he replied simply: "birdsong".

More than 59 adult tigers and 29 cubs are thought to live within this region, where tigers grow notably larger than elsewhere, Bhangre explained, sometimes reaching 300kg due to abundant fresh water and cattle in the area. Yet these elusive creatures are not always easy to spot. Unlike the rich abundance of animals encountered on safari in countries such as Kenya and South Africa, a tiger safari becomes more of a waiting game – hours spent listening for alarm calls from spotted deer and langur monkeys that signal a predator's presence nearby.

Tigers are elusive, so a safari is about waiting to see the spectacle

Bhangre's years of observation have revealed surprising tiger behaviours. He has witnessed them hunting in scorching 45C midday heat, far from water sources, challenging the common belief that they are strictly nocturnal creatures. "We know them and we don't know them," he reflects, acknowledging how much mystery still surrounds these apex predators.

That doesn't mean that your patience won't be rewarded. Great hornbills soar overhead while fishing cats prowl the wetlands. Grey fish eagles dive for their catch as oriental pied hornbills, indicators of a healthy, prosperous forest rich with mixed trees and fruits, call from the canopy. Green bee eaters dart through the air alongside woodpeckers and kingfishers, while Reece's macaques chatter in the branches. And then, when you least expect it, perhaps after hours of silent waiting, a tiger's amber eyes emerge from the tall grasslands. For a breathtaking moment, predator and observer hold each other's gaze before the tiger plunges back into the heart of the ancient forest.

Sorcha was a guest of Explorations Company, explorationscompany.com

Sorcha Bradley is a writer at The Week and a regular on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. She worked at The Week magazine for a year and a half before taking up her current role with the digital team, where she mostly covers UK current affairs and politics. Before joining The Week, Sorcha worked at slow-news start-up Tortoise Media. She has also written for Sky News, The Sunday Times, the London Evening Standard and Grazia magazine, among other publications. She has a master’s in newspaper journalism from City, University of London, where she specialised in political journalism.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

8 incredible destinations to visit in 2026

8 incredible destinations to visit in 2026The Week Recommends Now is the time to explore Botswana, Mongolia and Sardinia

-

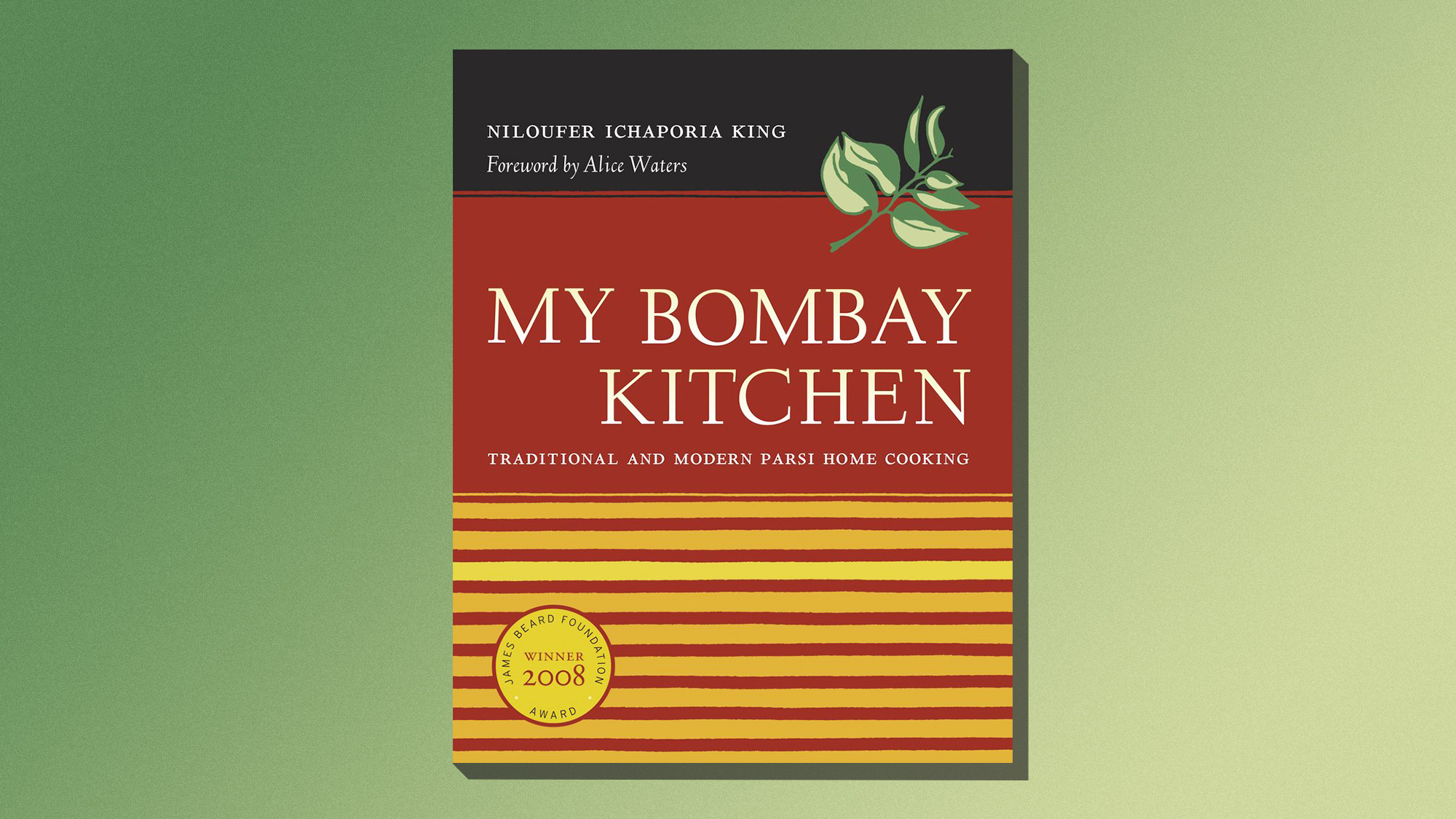

One great cookbook: Niloufer Ichaporia King’s ‘My Bombay Kitchen’

One great cookbook: Niloufer Ichaporia King’s ‘My Bombay Kitchen’The Week Recommends A personal, scholarly wander through a singular cuisine

-

Experience Tanzania’s untamed wilderness from Lemala’s luxury lodges

Experience Tanzania’s untamed wilderness from Lemala’s luxury lodgesThe Week Recommends The vast protected landscapes are transformed into a verdant paradise during ‘emerald season’

-

How digital ID cards work around the world

How digital ID cards work around the worldThe Explainer Many countries use electronic ID to streamline access to services despite concern by civil rights groups they ‘shift the balance of power towards the state’

-

What happened to Air India Flight 171?

What happened to Air India Flight 171?Today's Big Question Preliminary report reveals 'fundamental reason' why jet crashed, but questions remain about whether it was 'deliberate, accidental or if a technical fault was responsible'

-

Anshu Ahuja's golden coconut and butter bean curry recipe

Anshu Ahuja's golden coconut and butter bean curry recipeThe Week Recommends Plump, creamy beans in a sweet, spicy sauce

-

How to go on your own Race Across the World

How to go on your own Race Across the WorldThe Week Recommends The BBC hit show is inspiring fans to choose low-budget adventures

-

On the trail of the Iberian lynx

On the trail of the Iberian lynxThe Week Recommends Explore the culture, food – and wildlife – of Extremadura on this stunning Spanish safari