Stealing the Mona Lisa

Da Vinci's masterpiece became even more famous, says Simon Kuper, after Vincenzo Perugia swiped it from the Louvre in 1911

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

ON MONDAY MORNING, Aug. 21, 1911, inside the Louvre museum in Paris, a plumber named Sauvet came upon an unidentified man stuck in front of a locked door. The man, wearing a white smock, like all the Louvre's maintenance staff, pointed out to Sauvet that the doorknob was missing. The helpful Sauvet opened the door with his key and some pliers. The man walked out of the museum and into the Parisian heat wave. Hidden under his smock was Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa.

Stealing La Joconde — the woman in the portrait is probably Lisa del Giocondo, a Florentine silk merchant's wife — was not particularly difficult. Like the Louvre's other paintings, it was barely guarded. It wasn't fixed to the wall. The Louvre was closed on Mondays. On that particular Monday morning, the few caretakers were mostly busy cleaning. At 7:20 a.m., the thief was probably hiding in the storage closet, where he may have spent the night. All he had to do was wait until the elderly ex-soldier who was guarding several rooms wandered off, then lift the frame off its hooks, remove the frame from the painting, and shove the wooden panel on which Da Vinci had painted under his smock. The thief had chosen the Mona Lisa partly because it was so small: 21 inches by 30 inches. His one stumble was finding the door to his escape locked. He had already removed the doorknob with a screwdriver when the plumber saved him. By 8:30 a.m., the Mona Lisa was gone.

Twelve hours later, the caretaker in charge reported that everything was normal. Even the next morning, Tuesday, nobody had yet noticed the Mona Lisa's absence. Paintings in the Louvre often disappeared briefly. The museum's photographers were free to take works to their studio at will, without signing them out. When the painter Louis Béroud arrived on Tuesday morning to sketch the Mona Lisa and found only four iron hooks in the wall, he presumed the photographers had her. Béroud joked with the guard: "Of course, Paupardin, when women are not with their lovers, they are apt to be with their photographers." But when the Mona Lisa was still absent at 11 a.m., Béroud sent Paupardin to ask the photographers when it would be back, recounted R.A. Scotti in her excellent recent account, Vanished Smile. The photographers said they hadn't taken it, and the alarm was raised. In a corner of a service stairway, police found the glass box that had contained the painting and the frame donated two years earlier by the Comtesse de Béarn.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The theft was front-page news. "We still have the frame," said the Petit Parisien daily in a sarcastic subhead. The far-right Action Française newspaper blamed the Jews. Critics had pointed out the lack of security, but the museum had taken only a few eccentric corrective measures: teaching the elderly guards judo, for instance. Jean Théophile Homolle, director of all of France's national museums, had assured the press before leaving on his summer holidays that the Louvre was secure. "You might as well pretend that one could steal the towers of the cathedral of Notre-Dame," he said. After the theft, the French journalist Francis Charmes commented: "La Joconde was stolen because nobody believed she could be."

SOME JUDGES REGARD the painting as the finest existing," noted The New York Times. But even before the Mona Lisa disappeared, it was more than a painting. Leonardo's feat was to have made it almost a person. "Mona Lisa is painted at eye level and almost life-size, both disconcertingly real and transcendent," writes Scotti. Many romantics responded to the picture as if to a woman. The Mona Lisa received love letters, and it was given a touch more surveillance than the Louvre's other works, because some visitors stared at the "aphrodisiac" painting and became "visibly emotional," wrote Jérôme Coignard in Un Femme Disparaît. In 1910, one lover shot himself before Mona Lisa's eyes. After the theft, a French psychology professor suggested that the thief might be a sexual psychopath who would enjoy "mutilating, stabbing, defiling" the Mona Lisa. But nobody knew who the thief was, nor how he would profit from his haul. Monsieur Bénédite, the Louvre's assistant curator, told The New York Times: "Why the theft was committed is a mystery to me, as I consider the picture valueless in the hands of a private individual." If you had the Mona Lisa, what could you do with it?

The stricken Louvre closed for a week, but when it reopened, on Tuesday, Aug. 29, lines formed outside for the first time. People were streaming in to see the empty space where the Mona Lisa had hung. Unwittingly, Coignard writes, the Louvre was exhibiting the first conceptual installation in the history of art: the absence of a painting. The Mona Lisa was becoming a sensation. Scotti writes: "Chorus lines made up with the face of Mona Lisa danced topless in the cabarets of Paris....Comedians asked: 'Will the Eiffel Tower be next?'" The painting was celebrated in new popular songs ("It couldn't be stolen, we guard her all the time, except on Mondays"). Mona Lisa postcards sold in unprecedented numbers worldwide. Her face advertised everything from cigarettes ("I only smoke Zigomar") to corsets. No painting had ever been reproduced on such a scale. As Scotti says, it had suddenly become both "high culture" and "a staple of consumer culture."

The French police were under international pressure to find the thief. All they had to go on was a fingerprint he had left on the wall, and the doorknob he had thrown into a ditch outside. Employees and ex-employees were interrogated and fingerprinted — a newfangled technique in 1911 — but nobody's print matched the thief's. In December 1912, the Louvre hung a portrait by Raphael on its blank wall. The Mona Lisa had been given up for dead.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Then, on Nov. 29, 1913, an antiques dealer in Florence named Alfredo Geri received a letter postmarked Poste Restante, Place de la République, Paris. The author, who signed himself "Leonardo," wrote: "The stolen work of Leonardo da Vinci is in my possession. It seems to belong to Italy since its painter was an Italian." Geri showed the letter to Giovanni Poggi, director of Florence's Uffizi Gallery. Then Geri replied to Leonardo. Eventually Leonardo said it would be no trouble for him to bring the painting to Florence. Geri's shop was just a few streets from where Da Vinci had painted the Mona Lisa 400 years before. On the evening of Dec. 10, Leonardo unexpectedly walked in. He was a tiny man, 5 feet, 3 inches tall, with a waxed moustache. When Geri asked whether his Mona Lisa was real, Leonardo replied that he had stolen it from the wall of the Louvre himself. He said he wanted to "return" it to Italy in exchange for 500,000 lire in "expenses."

Geri arranged to come with Poggi to see the painting in Leonardo's room in the Tripoli-Italia hotel the next day. They went up to Room 20 on the third floor. Leonardo locked the door, dragged a case from under his bed, pulled out a package, and unwrapped it to reveal the Mona Lisa. The three men agreed that Poggi and Geri would take the painting to the Uffizi to authenticate it. At the Uffizi, Poggi established from the pattern of cracks that it was the real thing. After handing over the painting, Leonardo calmly went sightseeing in Florence. But then, to his surprise, he was arrested in his hotel room by Italian police.

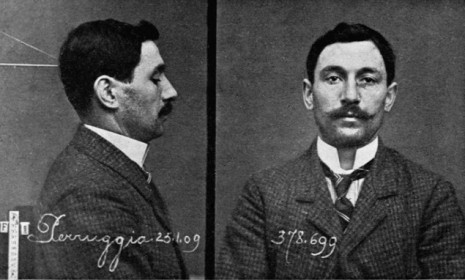

Leonardo turned out to be Vincenzo Peruggia, a 32-year-old Italian who lived in Paris. He was a house painter-cum-glazier. He suffered from lead poisoning. He lived in one room at 5 rue de l'Hôpital Saint-Louis, in a neighborhood of eastern Paris that even today is largely immigrant and ungentrified. The Mona Lisa had spent two years mostly on his kitchen table. "I fell in love with her," Peruggia said from jail, repeating the romantic cliché. The court-appointed psychiatrist diagnosed him as "mentally deficient." The French police really ought to have found him. Peruggia had briefly worked in the Louvre. In fact, he had made the Mona Lisa's glass box — the one he'd removed that August morning. A detective had even visited his apartment, but failed to spot the painting. He was locked up until his trial began in Florence, on June 4, 1914.

IN COURT, PERUGGIA emerged as the kind of disgruntled immigrant who in a different time might have turned to terrorism instead of art theft. In Paris he'd been insulted as a "macaroni." French people stole from him, and put salt and pepper in his wine. When he mentioned to a colleague at the Louvre that the museum's most esteemed paintings were Italian, the man chuckled. Peruggia had once seen a picture of Napoleon's troops carting stolen Italian art to France. He said he had become determined to return at least one stolen painting, the handily portable Mona Lisa, to Italy. In fact, the French hadn't stolen the Mona Lisa at all. Da Vinci had spent his final years in France. His last patron, the French king François I, had bought the painting, apparently legally, for 4,000 gold crowns.

After Peruggia's arrest, there was a brief flare-up of patriotic peruggisme in Italy, but it soon died down. Most people were disappointed in Peruggia's calibre. Still, he was lucky to be tried in Italy rather than France. In Italy, his lawyer said in his closing argument — to applause from spectators and tears from the defendant — "there is nobody who desires the condemnation of the accused." Nobody had lost anything from the theft, the lawyer pointed out. The Mona Lisa had been recovered. It was now more famous than ever. It had made a brief, joyous tour of Italy before returning to the Louvre. Peruggia received a sentence of one year and 15 days in jail. Some weeks later, it was reduced to seven months and nine days. He was released at once because of time served. Peruggia later returned to France and opened a paint shop in a village in Haute-Savoie. He died there in 1925, aged 44, perhaps from the consequences of lead poisoning.

THE OTHER DAY I went to the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa. I wasn't the only one. From the moment you enter the museum, you see signs pointing to it. You walk into the room where it hangs and find a crowd of a couple of hundred people, their backs to you, many with mobile phones above their heads taking photographs. Somewhere in the distance is a surprisingly small picture of a smiling woman, mostly obscured by phones. Its myth stems, in part, from the story of its theft and return. "A painting had been turned, anthropomorphically, into a person, a celebrity," wrote Donald Sassoon in his book Becoming Mona Lisa. Peruggia, by choosing the Mona Lisa that morning, helped to elevate it above all other paintings. That — and a good story — is his legacy.

By Simon Kuper. A longer version of this article first appeared in the Financial Times. ©2011 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved.