Can antibiotics make you fat?

New research suggests that taking medicine for ear infections might be related to a reckless appetite

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Antibiotics have done wonders for extending human life by killing off deadly pathogens. But they target "a particular disease the way a nuclear bomb targets a criminal, causing much collateral damage," says Karen Kaplan in the Los Angeles Times. Incidental victims include a whole host of microbes that actually help us, and "our friendly flora never fully recover," argues New York University microbiologist Martin Blaser in the journal Nature. The unintended targets of antibiotics might also include our waistlines, according to new theories linking the drugs to a sharp rise in obesity. Here's what you need to know:

How do antibiotics hurt us?

Bacteria have lived in and on us as long as there have been humans, creating a symbiotic relationship. But that's changed over the past 80 years, Blaser says, because the development of antibiotics started disrupting the population of mostly beneficial bacteria that help us digest our food, metabolize vitamins and nutrients, and even fight off invading organisms. "Antibiotics kill the bacteria we do want, as well as those we don't," he notes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And there's evidence of this?

Blaser points to Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium he's worked with for 26 years. Discovered in 1982, H. pylori "has been the dominant ancient organism of the human stomach since time immemorial," he tells The Scientist. Now it's disappearing. In the early 1900s, it thrived in the guts of all people; today, fewer than 6 percent of American, Swedish, and German kids have any trace of H. pylori. A likely cause, says Blaser, is antibiotics: A single course of amoxicillin or other antibiotics used to clear up, say, an ear infection, also wipes out H. pylori up to 50 percent of the time.

Is losing a little bacteria really so bad?

In the case of H. pylori, it appears to be a mixed blessing: The bacterium promotes gastric cancer and ulcers, which have gotten rarer along with the microbe. But Blaser's lab has also shown that kids lacking H. pylori are more prone to asthma, hay fever, and skin allergies. "And H. pylori is just one bacterium!" says Karen Kaplan in the L.A. Times.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Wait, what does this have to do with obesity?

H. pylori also affects the behavior of two stomach-producing hormones that control hunger — ghrelin, which tells the brain you're hungry, and leptin, which tells it you're full. If those hormones are thrown out of balance, your appetite probably is, too. Blaser says the rise in antibiotic use tracks with sharp increases in obesity. (Half of U.S. adults will be obese by 2030, according to a new study published in the journal The Lancet.) That's not proof the two trends are related, he concedes, but it's a fertile path for exploration.

Is there any way to reverse this trend?

A general reduction in the use of antibiotics is a good first step, Blaser says, but we also need to develop a new generation of antibiotics that more surgically target specific pathogens. And someday, he tells The Scientist, doctors will find what microbes infants are lacking, "and just as a child gets their immunizations, they'll get a dose of the missing bacteria so that they can get the early life benefits just as all their forebears have."

Sources: Gizmodo, LiveScience, Los Angeles Times, The Scientist, Waleg, Washington Post

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

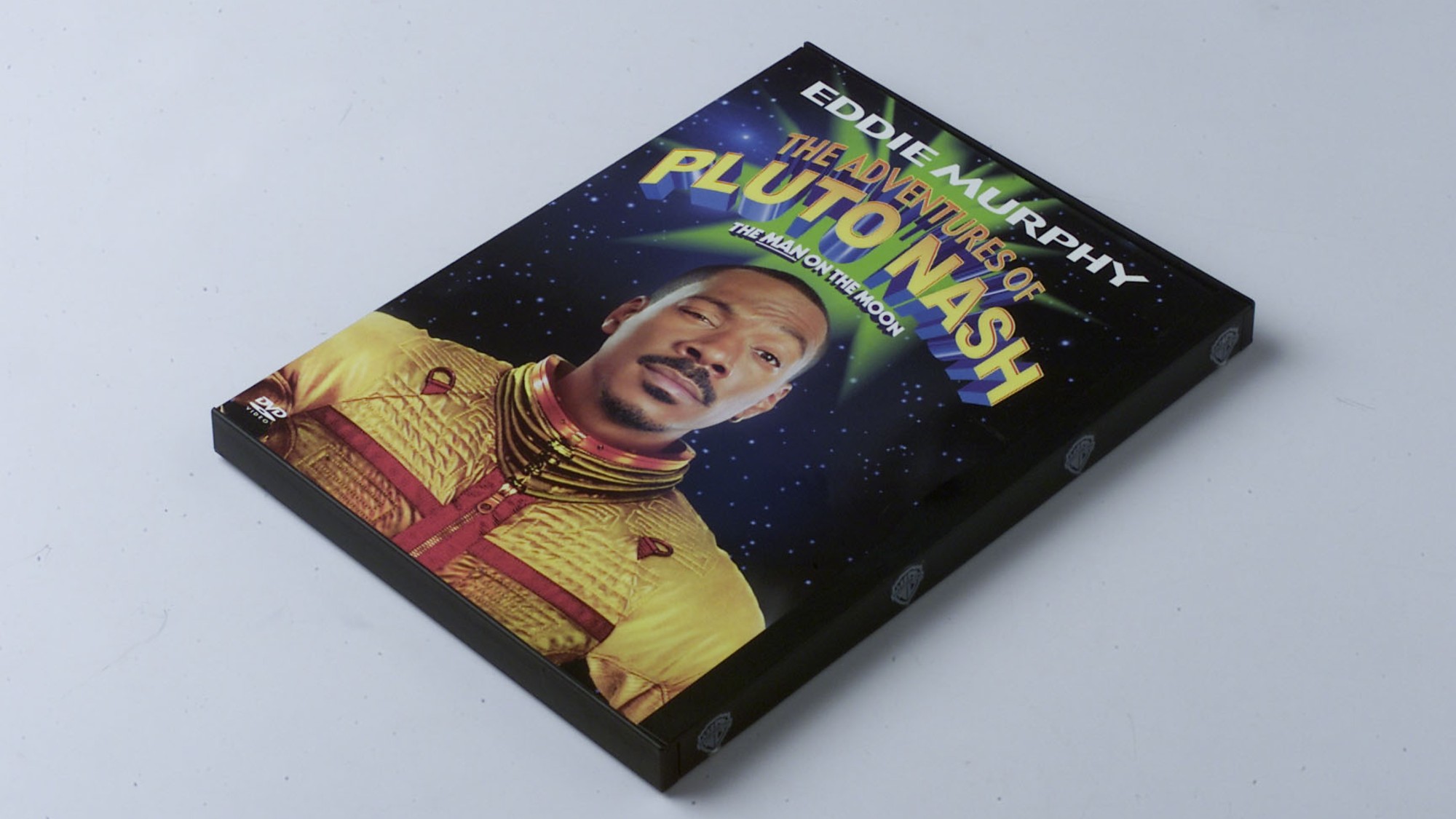

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my