Exhibition of the week: Reclaimed: Paintings From the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker

The story behind Jacques Goudstikker’s art collection is as remarkable as the collection itself. The exhibit at the Bruce Museum is the last and best chance to see 40 paintings from the collection before they are sold at auction.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Exhibition of the week

Reclaimed: Paintings From the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker

Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Conn.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Through Sept. 7

Jacques Goudstikker’s life was dedicated to high culture, but his death was “a savage joke,” said Matthew Gurewitsch in The Wall Street Journal. On May 13, 1940, the renowned Dutch art dealer fled the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands, along with his wife and infant son. Two days later he fell on the deck of a ship, off the shore of England, and died. Goudstikker left behind a remarkable collection of 1,400 Renaissance masterpieces, and the trove was soon seized by the Nazis. “Hitler’s rapacious second-in-command,” Hermann Göring, took many works for his own collection. After the war, Allied forces were able to recover only a fraction of those, which were repatriated to the Netherlands with the understanding that they would be returned to Goudstikker’s heirs.

“They were not,” said Maureen Mullarkey in The New York Sun. In fact, the Netherlands compounded the original injustice by adding 200 of Goudstikker’s paintings to its national collections. Only a protracted court battle restored these works to Goudstikker’s heirs, who now plan to sell them at auction. Thus this gathering of 40 pieces is the last, best chance to see Goudstikker’s paintings in one place. The “spectacular collection” is a grab bag of masterpieces, incorporating important works in various eras and styles. Daniel Vosmaer’s panoramic View of Delft (1663) is one of the earliest Renaissance cityscapes. Jan Mostaert’s Landscape With an Episode From the Conquest of America or Discovery of America (c. 1520–40) “is famed as the earliest painted representation of the New World.”

Besides landscapes, Goudstikker had an eye for “richly textured portraits and psychologically taut history paintings,” said Georgette Gouveia in the Westchester, N.Y, Journal News. Paintings of biblical and mythical topics, in particular, bristle with hidden implications. Pieter Lastman’s David Gives Uriah a Letter for Joab (1619), for instance, shines with “psychological subtlety” when you consider that the Hebrew king is handing the servant his own death sentence. But one painting stands out “as first among equals”: Jan Steen’s 1671 oil The Sacrifice of Iphigenia. This image of the brave Greek princess—doomed to die so the Greeks might be victorious at war—well symbolizes “all those who responded to the Nazis with a heroic, existential stance.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

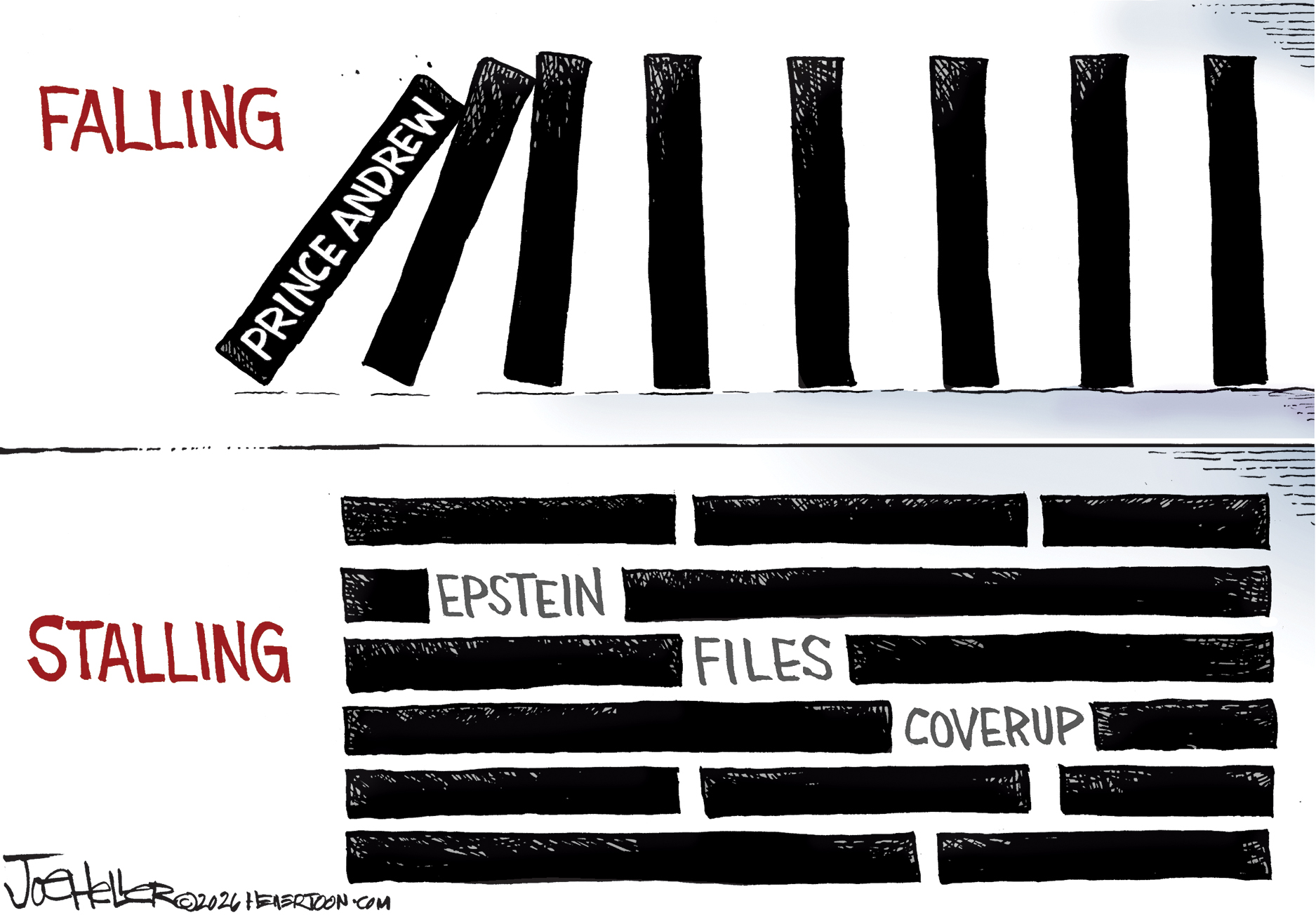

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

If/Then

feature Tony-winning Idina Menzel “looks and sounds sensational” in a role tailored to her talents.

-

Rocky

feature It’s a wonder that this Rocky ever reaches the top of the steps.

-

Love and Information

feature Leave it to Caryl Churchill to create a play that “so ingeniously mirrors our age of the splintered attention span.”

-

The Bridges of Madison County

feature Jason Robert Brown’s “richly melodic” score is “one of Broadway’s best in the last decade.”

-

Outside Mullingar

feature John Patrick Shanley’s “charmer of a play” isn’t for cynics.

-

The Night Alive

feature Conor McPherson “has a singular gift for making the ordinary glow with an extra dimension.”

-

No Man’s Land

feature The futility of all conversation has been, paradoxically, the subject of “some of the best dialogue ever written.”

-

The Commons of Pensacola

feature Stage and screen actress Amanda Peet's playwriting debut is a “witty and affecting” domestic drama.