The last word: An affair to remember

She was 82. He was 95. They both had dementia. When they started having sex, says Melinda Henneberger in Slate.com, relatives and caregivers were thrown for a loop.

Bob’s family was horrified at the idea that his relationship with Dorothy might have become sexual. At his age, they wouldn’t have thought it possible. But when Bob’s son walked in and saw Bob’s 82-year-old girlfriend performing a sex act on his 95-year-old father last December, incredulity turned into full-blown panic. His graphic and sputtering cell phone call to the manager of the couple’s assisted-living facility would have been funny, the manager later said, if the consequences hadn’t been so serious.

Because both Bob and Dorothy suffer from dementia, the son assumed that his father didn’t fully understand what was going on. He became determined to keep the two apart and asked the facility’s staff to ensure that they were never left alone together.

After that, Dorothy stopped eating. She lost 21 pounds, was treated for depression, and was hospitalized for dehydration. When Bob was finally moved out of the facility in January, she sat in the window for weeks waiting for him. She doesn’t do that anymore, though: “Her Alzheimer’s is protecting her at this point,” says her doctor, who thinks the loss might have killed her if its memory hadn’t faded so mercifully fast.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But should someone have protected the couple’s right to privacy—their right to have a sex life?

“We were in uncharted territory,” the facility manager said—and there’s a reason for that. Even the More magazine-reading demographic that thinks midlife is forever (and is deeply sorry to see 62-year-old actor James Naughton doing Cialis ads) seems to believe that while sex isn’t only for the young, exceptions are only for the exfoliated. We’re squeamish about the sex lives of the elderly—and even more so when those elderly are senile and are our parents. But as the baby boom generation ages, there are going to be many more Dorothys and Bobs—who may no longer quite recall the Summer of Love, but are unlikely to accept parietal rules in the nursing home. Gerontologists highly recommend sex for the elderly because it improves mood and even overall physical function, but the legal issues are enormously complicated. Can someone with dementia give informed consent? How do caregivers balance safety and privacy concerns? When families object to a demented person being sexually active, are nursing homes responsible for chaperoning? This one botched love affair shows the

incredible intensity and human cost of an issue that, as Dorothy’s doctor says, we can’t afford to go on ignoring.

Dorothy’s daughter, who contacted me, said that, in a lucid moment, her mother asked her to publicize her predicament. “We’re all going to get old, if we’re lucky,” said the daughter, who is a lawyer. And if we get lucky when we’re old, then we need to have drawn up a sexual power of attorney before it’s too late. Who controls the intimate lives of people with dementia? Unless specific provision has been made, their families do. And for Dorothy, which is her middle name, and Bob, which isn’t his real name at all, that quickly became a problem.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“Who do you love?” Dorothy asked me, right after her daughter introduced us. She’d married her first—and only other—sweetheart, a grade-school classmate she’d grown up with in Boston and waited for while he flew daylight bombing raids over Germany during World War II. Together they had four children, built a business, and traveled all over the world, right up until she lost him to a heart attack 16 years ago. But she never mentions him now and doesn’t like it when anyone else does, either, because how could she not remember her own husband?

But even showing me around her well-appointed little apartment in the nice-smelling assisted-living facility was an exercise in frustration for Dorothy: She joked and covered, but she might as well have been guiding me through a stranger’s house, because all around were tokens from her past that have lost their meaning for her. There were tiny busts of Bach and Brahms, a collection of miniature pianos, Japanese woodcuts, and some Thomas Hart Benton lithographs she picked up for a few dollars in the ’40s. “These are all my favorites,” she said, pointing to shelves of novels by the Brontës and books about Leonardo da Vinci and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. But her expression said that she couldn’t recall why she liked these volumes best, and what I think she wanted me to know is that she once was a person who could have told me. When her daughter mentioned Bob’s name—Bob, who was led away in January, shouting, “What’s going on? Where are you taking me?” right in front of her—it wasn’t clear how much she remembered: “He came and he went, and there’s nothing more to say.”

So it was left to her daughter, her doctor, and the woman who runs the assisted-living facility to explain how this grown woman, who lived through the Depression and survived breast cancer, managed a home, and mourned a mate, wound up being treated like a child. “Come back anytime,” Dorothy told me sweetly.

Downstairs, in her bright, tidy office, I met the woman who runs the facility—one of the nicest I’ve seen, with tea service in the lobby and white tablecloths in a dining room that’s dressed up like a restaurant. In 30 years of taking care of the elderly, she has seen plenty of couples, but none as “inspiring” or heartbreaking as Dorothy and Bob. Which is why she keeps a photo of the two of them on her desk. In the picture, Dorothy is sitting at the piano in the lobby, where she used to play and he used to sing along—with gusto, usually warbling, “I dream of Jeanie with the light brown hair,” no matter what tune she was playing. She is all dolled up, wearing a jangly red bracelet and gold lamé shoes, and they are holding hands and beaming in a way that makes it impossible not to see the 18-year-olds inside them.

Before Dorothy came along, the manager said, Bob was really kind of a player and had all the women vying to sit with him on the porch. But with Dorothy, she said, “it was love.” One day, the staff noticed that they were sitting together, and before long they were taking all their meals together. Whenever Bob caught sight of Dorothy, he lit up “like a young stud seeing his lady for the first time.” Even at 95, he’d pop out of his chair and straighten his clothes when she walked into the room. Both of them began taking far greater pride in their appearance; Dorothy went from wearing the same ratty yellow dress all the time to appearing for breakfast every morning in a different outfit, accessorized with pearls and hair combs.

Soon the relationship became sexual. At first, Dorothy’s daughter and the facility manager doubted Dorothy’s vivid accounts of having intercourse with Bob. But aides noticed that Bob became visibly aroused when he kissed Dorothy good night—and saw that he didn’t want to leave her at her door anymore, either. (Note to James Naughton: Bob did not need what you are selling.) His overnight nurse was an obstacle to sleepovers, but the couple started spending time alone in their apartments during the day. When Bob’s son became aware of these trysts, he tried to put a stop to them—in the manager’s view because the son felt that old people “should be old and rock in the chair.” When I called Bob’s son and told him I was writing about the situation without using any names, he passed on the opportunity to explain his perspective. “I don’t choose to discuss anything that involves my father,” he said, and he put the phone down.

But according to the facility manager, the son was convinced that Dorothy was the aggressor in the relationship, and he worried that her advances might be hard on his father’s weak heart. He wasn’t the only one troubled by the physical relationship. The private-duty nurse who had been tending Bob also had strong feelings about the matter, said the manager: “At first, she thought it was cute they were together, but when it became sexual, she lost her senses”—for religious reasons—and asked staff members to help keep the two of them apart.

Employees wound up choosing sides—as did other residents, including some women who were apparently jealous of Dorothy’s romance. And because the couple now had to sneak around to be together—for instance, cutting out when they were supposed to be in church—their intimacy became more and more open and problematic. In all of her years of working with elderly people, the manager said, this was the only case that left her feeling she had failed her patients. She had a hard time staying neutral, she said, because she kept thinking that “if that was my mom or dad, I’d be grateful they’d found somebody to spend the rest of their lives with.”

One day when Dorothy’s daughter arrived to visit, she found Bob sitting in the lobby, surrounded by a wheelchair brigade of dozing people who had been posted around him by the private-duty nurse to block Dorothy from approaching him. That’s when Dorothy’s daughter started throwing around the word lawsuit, which only made things worse. “Once she started talking legal,” the manager said, “that pushed things over the edge.”

Finally, Bob’s family decided to move him and insisted that neither he nor Dorothy be told in advance. No one in either family was there the morning Bob’s nurse hustled him out the door. Later, the manager called his son and asked if there was any way Dorothy might come and visit just briefly, to say goodbye. The son thought about it for a few days and then said no, his father was already settled into his new home and was not thinking about her at all anymore.

Though Dorothy might or might not remember what happened, “there’s a sadness in her,” the manager said, that wasn’t there before. Dorothy eats in her room now rather than in the dining room with others. And she no longer plays the piano.

Her doctor has found the change painful to witness. “Can you imagine as a clinician, treating a woman who’s finally found happiness and then suddenly she’s not eating because she couldn’t see her loved one? This was a 21st-century Romeo and Juliet.”

“We can’t afford the luxury of treating people like this,” he added, recalling Dorothy’s depression, and her resulting malnutrition and dehydration. “But we don’t want to know what our parents do in bed.”

Dorothy’s daughter then interjected that Bob’s son certainly didn’t want to see them having oral sex, and the doctor proved his own point. Holding a hand up to stop her from saying any more, he told her, “I didn’t need to know that.” But maybe the rest of us do.

From a story published by Slate.com. Used with permission of Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive. All rights reserved.

-

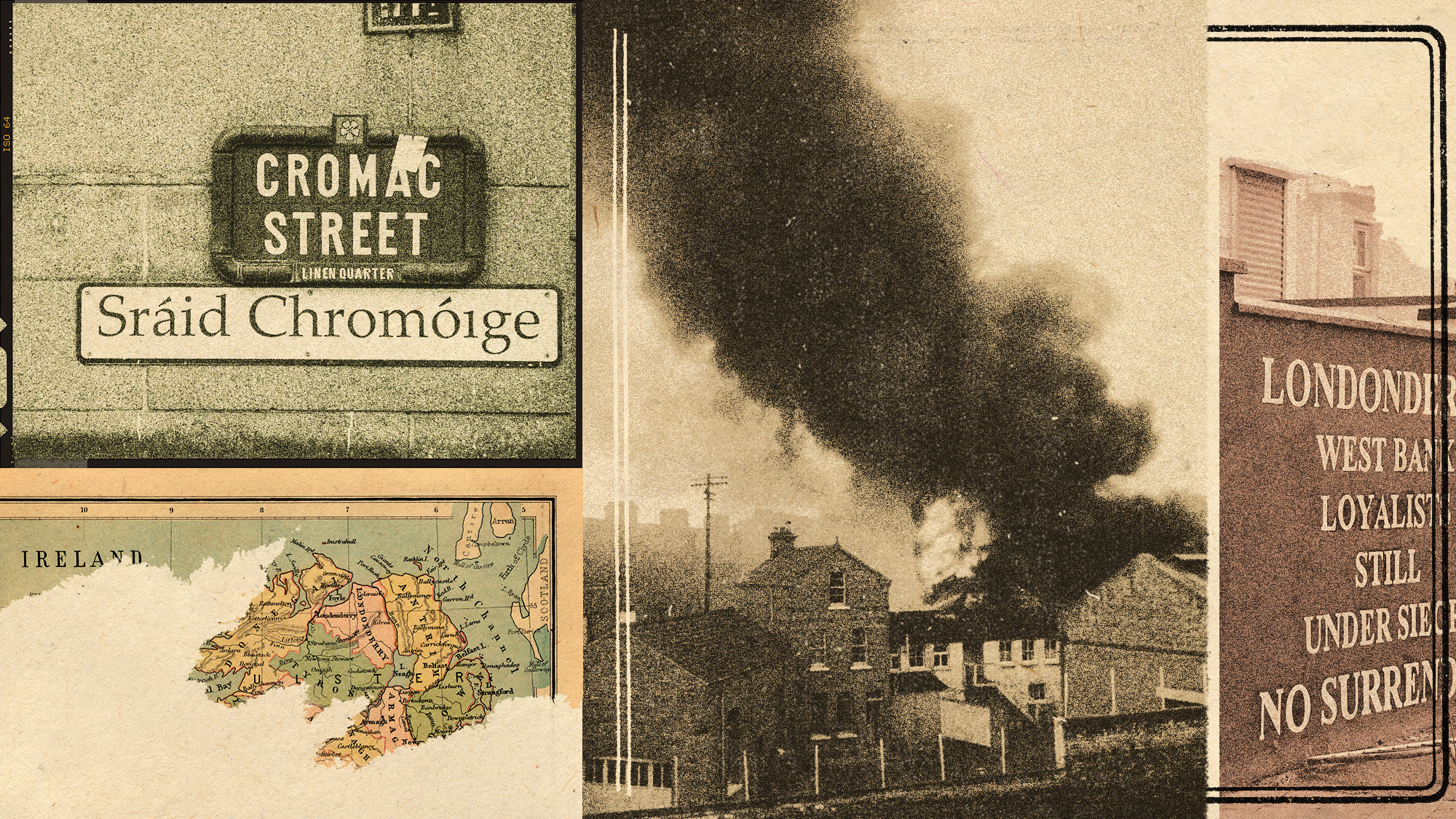

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels

-

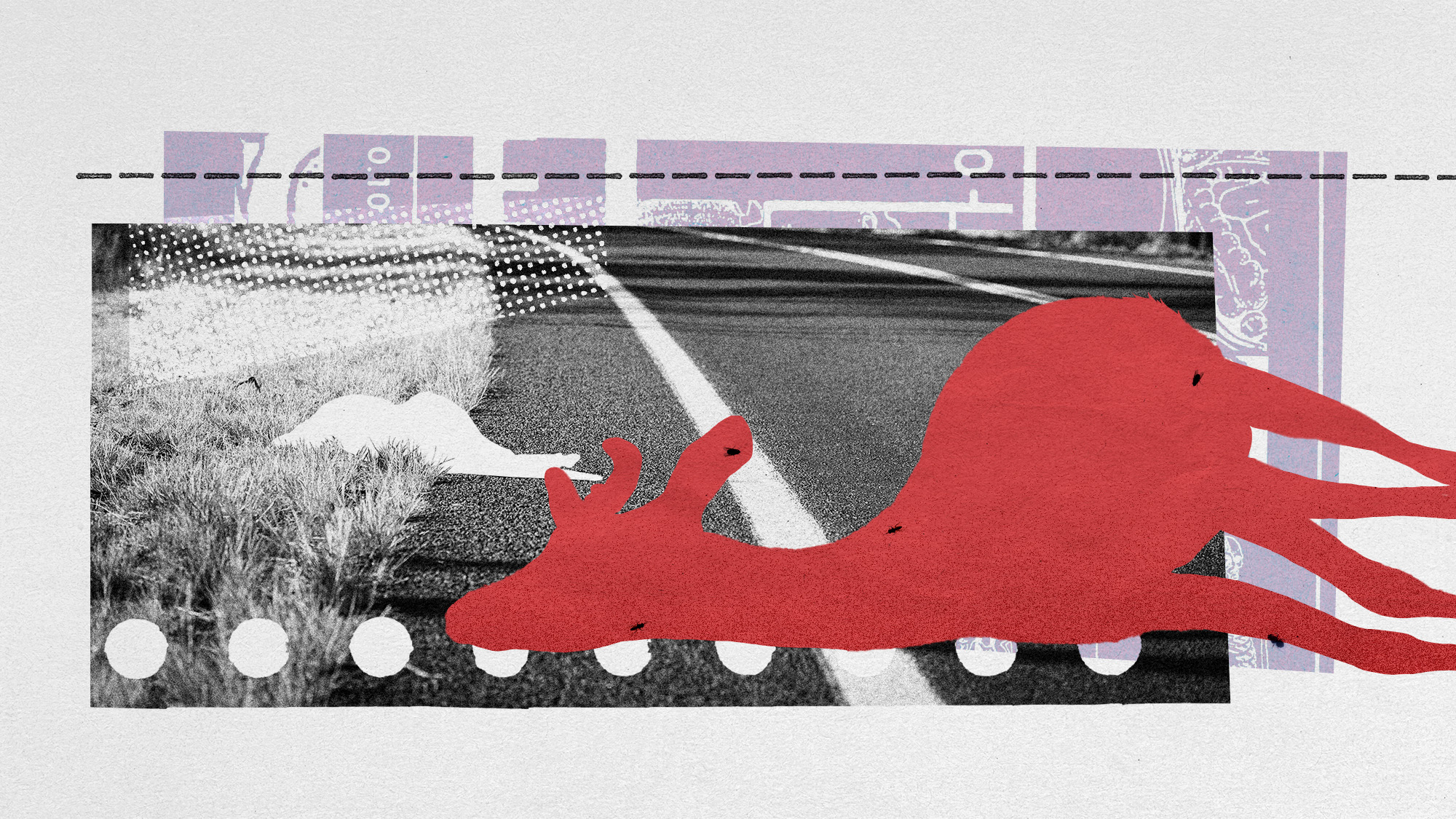

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them