The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

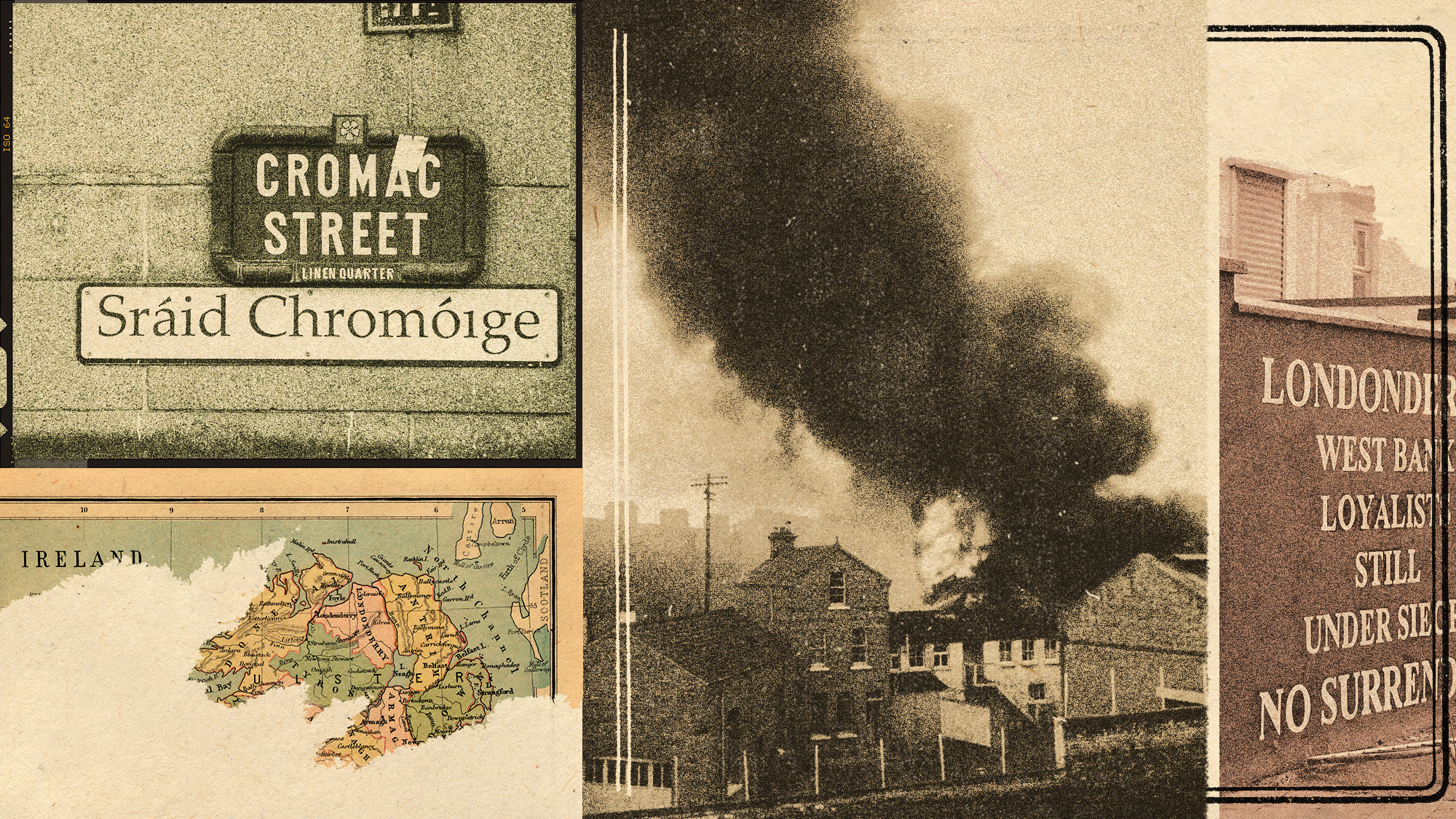

In Northern Ireland, where the Irish language is a proxy battleground between Unionists and Nationalists, dual-language signs have become a “key point of contention at Stormont”, said the BBC.

In October, Belfast City Council approved a draft policy to promote its use in public life, with bilingual signs across its facilities and official buildings. Sinn Féin hailed it as a “historic milestone” for a long-marginalised language.

But unionists objected, triggering a mechanism to “scrutinise the legitimacy of the decision”, said the Belfast Telegraph. Communities minister Gordon Lyons claimed some were using the language as a “weapon of cultural dominance”. The legal action has now arrived at the High Court.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A ‘greening’ of Ulster?

“What was once dismissed as a fading tongue is undergoing an exhilarating and vibrant revival”, said The Irish Times. North of the border, Belfast is leading the way. Bilingual street signs, permitted in Northern Ireland since the peace process, previously required approval by a two-thirds majority of residents. That was typically reached only in majority-Catholic neighbourhoods. But Belfast reduced the approval threshold to just 15% in 2022.

The dual-language signs are sparking anger in some areas “badly scarred by the Troubles”. “In a land where territory has long been marked by murals, flags and kerbstones daubed in national colours, they see the rollout of Irish signs as a ‘greening’ of Ulster by nationalists.” Existing bilingual street signs in the capital “have been vandalised more than 300 times in five years”, according to the BBC.

First Minister Michelle O’Neill and her deputy have been “unable to agree a joint position” on the latest Belfast policy, and won’t mount a challenge to the High Court action, said Irish News. Justice McLaughlin has reserved judgment on the legality of the policy, saying: “I’ve got an awful lot to think about.” Until then, the draft proposal remains on hold.

Irish language ‘imposed’

Irish was declared the first official language of the Irish Free State in 1921, but in the six counties that remained in the UK as Northern Ireland, the language continued to be suppressed and treated with suspicion by the authorities. Less than 2.5% of the population in Northern Ireland speaks it daily, according to 2021 census figures.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, the government, which “suppressed Irish for decades, is now openly boosting it”, said The Washington Post. The Identity and Language Act of 2022 bestowed official, protected status on the Irish language in Northern Ireland and overturned a ban of almost 300 years on its use in court.

Last year, Stormont appointed Northern Ireland’s first Irish language commissioner to promote its use across public bodies. Irish-language schools and classes are growing in popularity, “even among Protestant parents”, marking a “stark shift in attitudes about culture, identity and heritage that are gaining pace throughout Belfast”.

The language has “scored cultural breakthroughs”, said The Guardian. Popular Belfast hip-hop trio Kneecap, who sing primarily in Irish, “have given the language a punk cachet” and are credited with sparking increased uptake in classes.

“However, beneath all this buzz lies a battleground,” said The Irish Times. The Irish language remains “highly politically charged across Northern Ireland”. Unionist leaders reject “what they see as an erosion of their identity and traditions”.

“There are some who wish to see Irish imposed on the whole society,” Clive McFarland, a spokesperson for the Democratic Unionist Party, told The Washington Post. They are “trying to make Northern Ireland less like the United Kingdom and more like the Republic of Ireland”, with the goal of a referendum on reunification.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.