Briefing: When bullies go online

What is cyberbullying? Online bullying comes in many forms. Cyberbullies flood their targets with nasty e-mails or text messages. They set up websites devoted to attacking their victims or spread rumors and personal attacks via chat rooms. A clever harass

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is cyberbullying?

Online bullying comes in many forms. Cyberbullies flood their targets with nasty e-mails or text messages. They set up websites devoted to attacking their victims or spread rumors and personal attacks via chat rooms. A clever harasser can even steal another teen’s user name and use it to send out messages that appear to be from that teen. That’s what happened to eighth-grader Kylie Kenney of South Burlington, Vt. Someone stole her ID and sent out text messages that indicated that she was a lesbian. Then a website went up called “Kill Kylie Incorporated,” complete with a slew of crude insults under the heading, “She’s queer because ...”

How common is this kind of harassment?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some 32 percent of teenagers who use the Web report having received threatening or harassing messages or having had ugly rumors spread about them online, a recent Pew survey found. That’s three times the number from just three years ago. One in eight teens has felt scared enough after receiving online threats to have stayed out of school, says the National Crime Prevention Council, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that teenagers harassed online are more likely to experience emotional stress and get into trouble. While there have always been bullies, “there’s a greater potential for emotional harm from cyberbullying,” said Nancy Willard of the Oregon-based Center for Safe and Responsible Internet Use, “because it occurs 24/7 and the audience is much wider.”

Who typically gets picked on?

Just as in the real world, it’s often the kids who stand out for one reason or another. One middle-school girl interviewed for the Pew study told how a gay friend’s online profile had gotten hacked. “Someone put all this really homophobic stuff on there and posted like a mass bulletin of like some guy with his head smashed open,” she said. “It was really gruesome.” A 16-year-old Chicago girl described how she and her friends slammed a student on MySpace: “There’s this boy in my anatomy class who everybody hates. He’s like the smart kid in class. And some girl in my class started this I Hate [the boy’s name] thing. So everybody in school goes on it to comment.” A popular middle-school girl whom other kids envied was baffled when her classmates suddenly started shunning her. It turned out that someone had launched a text-message rumor that she had contracted SARS.

What’s behind this trend?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

With kids spending so much time in cyberspace, it was probably inevitable. Mean kids have always preyed upon more vulnerable types in locker rooms, on playgrounds, and elsewhere. But cyberbullying is even easier to carry out, because it can be done anonymously and from a safe distance. “People are too wussie to stand up to the person in real life,” said 16-year-old Colleen Harris of Minneapolis, who endured a battery of online name-calling. “So they decide to go on the computer and send mean, nasty messages.” Indeed, one study found that nearly two-thirds of youngsters harassed online had never been bullied face to face. “The person who could be bullying you [anonymously online],” said Monterey, Calif., school administrator Jo Ann Allen, “may be acting like your best friend at school.”

What’s the impact on victims?

Many shrug it off, but others are traumatized. When 14-year-old Olivia Gardner of Novato, Calif., discovered an “Olivia Haters” Web page filled with slurs such as “bitch” and references to “kicking her ass,” she became so upset that she had to change schools. The harassment continued, and Olivia’s parents eventually decided to home-school her. Some victims have even committed suicide. In a high-profile case that created national headlines last year, 13-year-old Megan Meier of Missouri killed herself after she was courted online and then dumped by a boy she knew as “Josh Evans.” It later emerged that “Josh” was the creation of a girl who had had a falling-out with Megan. The girl’s mother actually helped her daughter perpetuate the ruse.

What’s being done about such behavior?

The Meier case prompted many websites, school districts, and state legislators to try to address the problem. MySpace set up a special cyberbullying hotline, while schools are adding “online behavior” to their codes of conduct. Nine states have either incorporated electronic harassment into existing harassment statutes or established it as a separate offense, while five states are considering such legislation. A few states have also passed laws to give school districts greater authority to intervene even in incidents that don’t take place on school grounds.

Are these efforts making much difference?

It doesn’t appear so. For starters, enforcing these laws can be difficult because of constitutional roadblocks. “Harassment runs squarely into First Amendment rights, particularly over the Internet,” said computer law expert J. Bradley Young. “Where does free speech end and harassment begin?” Another problem is that many of the laws put the onus on schools to deal with the problem, but educators say their ability to monitor, let alone stop, actions that take place outside school is severely limited. As a result, for some kids, there simply is no respite from the mean-spirited taunts of their classmates. “When students used to be bullied at school, home was a safe place,” said Marji Libshez-Shapiro of the Anti-Defamation League in Connecticut. “Now the bullying follows them home.”

The death of a cybervictim:

Ryan Patrick Halligan of Essex Junction, Vt., was a musically gifted kid, though he was physically awkward. In middle school, tormenters began bombarding him with instant messages calling him gay, and his classmates began gossiping about him online. By eighth grade, Ryan was so consumed by the online chatter that he became isolated and morose. Sometimes he would emerge from his room in tears after hours online, but he never wanted to talk about it. Then, on Oct. 7, 2003, Ryan, age 13, hanged himself. Only afterward did his father, John, who has since launched a cyberbullying awareness campaign, get on Ryan’s computer and uncover his electronic trail. Among the e-mail messages he found was one from a girl Ryan had had a crush on; she told him she had shared all the e-mails he had sent to her with others, because he was a “loser.” One exchange of instant messages was particularly chilling. When Ryan told a classmate he was ready to kill himself, the youngster responded, “It’s about [expletive] time.”

-

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTU

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTUIN THE SPOTLIGHT How does the party out of power plan to mark the president’s first State of the Union speech of his second term? It’s still figuring that out.

-

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanches

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanchesThe Explainer Several major ones have recently occurred

-

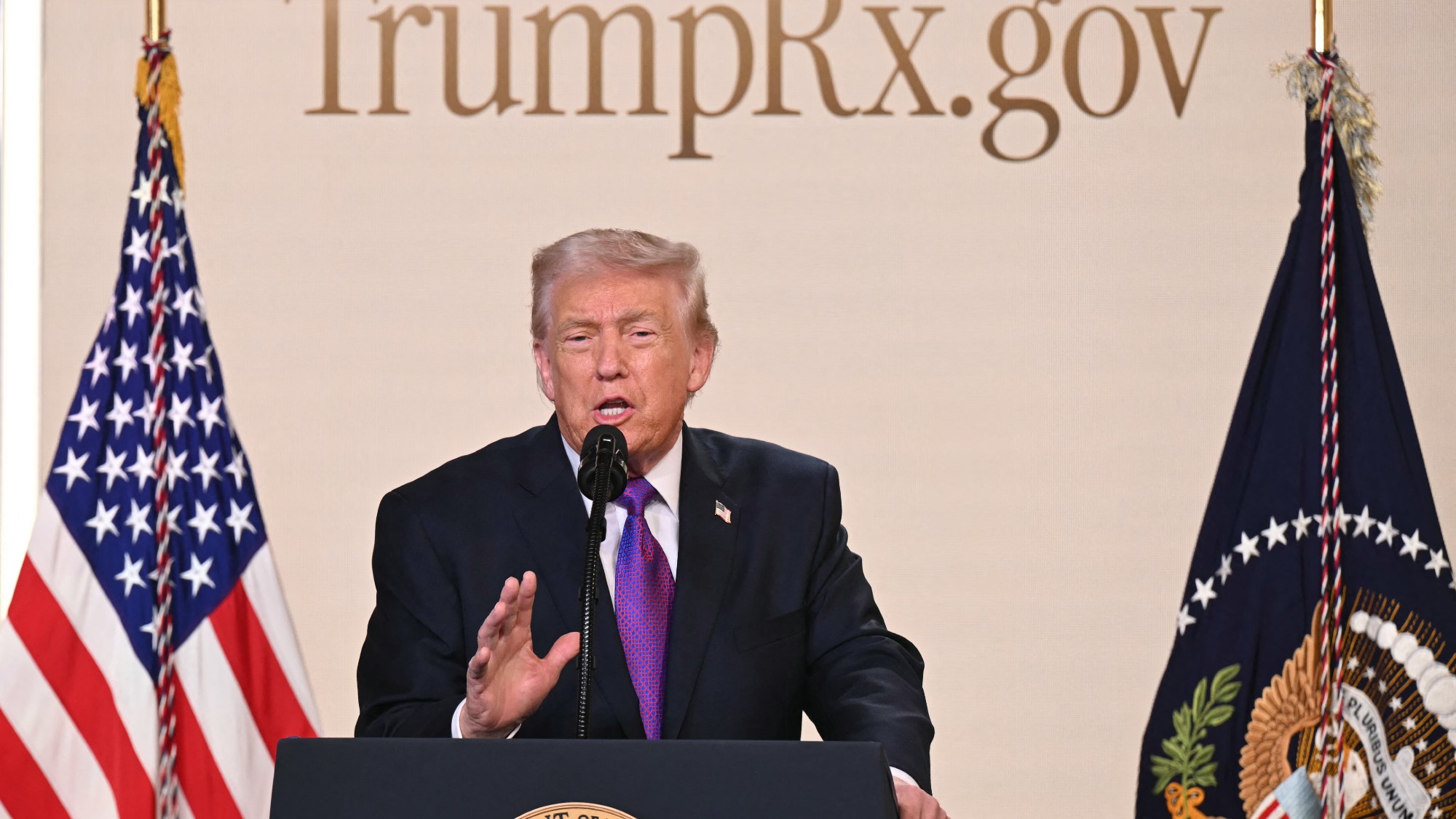

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?The Explainer The new drug-pricing site is designed to help uninsured Americans

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred