Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Frida Kahlo

Walker Art Center

Minneapolis

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Through Jan. 20, 2008

Frida Kahlo’s “vibrant paintings loom so large in 20th-century art” that you may be surprised how physically small most of them are, said Mary Abbe in the Minneapolis Star- Tribune. Of the 46 paintings united at the Walker Art Center’s retrospective— more than half of the Mexican artist’s lifetime output—many are “not much larger than sheets of copier paper.” They are, in part, a visual biography of a life filled with physical suffering. From childhood polio to a terrible bus accident and violent miscarriage later in life, Kahlo lived in constant pain. “Like the paintings of Vincent Van Gogh or the poetry of Sylvia Plath, Kahlo’s work is so entwined with her biography that it reads as a road map of a tormented soul.” Kahlo first gained fame in the 1930s, when she married painter Diego Rivera and began exhibiting with the surrealists, said Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker. She turned out to be a finer artist than any of them. Her realistic still-lifes of fruit, flowers, and animals have greater psychological depth than the surrealists’ more ethereal flights of fancy, and “her selfportraits cannot be overpraised.” Overflowing with colors, they have a lush, sensual invitingness that simply doesn’t come across in reproduction. “The tactility of certain selfportraits is, among other things, staggeringly sexy.” This exhibition includes several Kahlo masterpieces, from the warm Me and My Parrots (1941) to the chilling The Broken Column (1944). For Frida fans such as myself, the exhibition provides an unprecedented chance to trace the unusually close relationship between her life and her art. Even the works here that aren’t in themselves great art are valuable as the “moving testaments of a great artist.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Rock Villa, Bequia: a hidden villa on an island epitomising Caribbean bliss

Rock Villa, Bequia: a hidden villa on an island epitomising Caribbean blissThe Week Recommends This gorgeous property is the perfect setting to do absolutely nothing – and that’s the best part

-

Mexico’s vape ban has led to a cartel-controlled black market

Mexico’s vape ban has led to a cartel-controlled black marketUnder the Radar Cartels have expanded their power over the sale of illicit tobacco

-

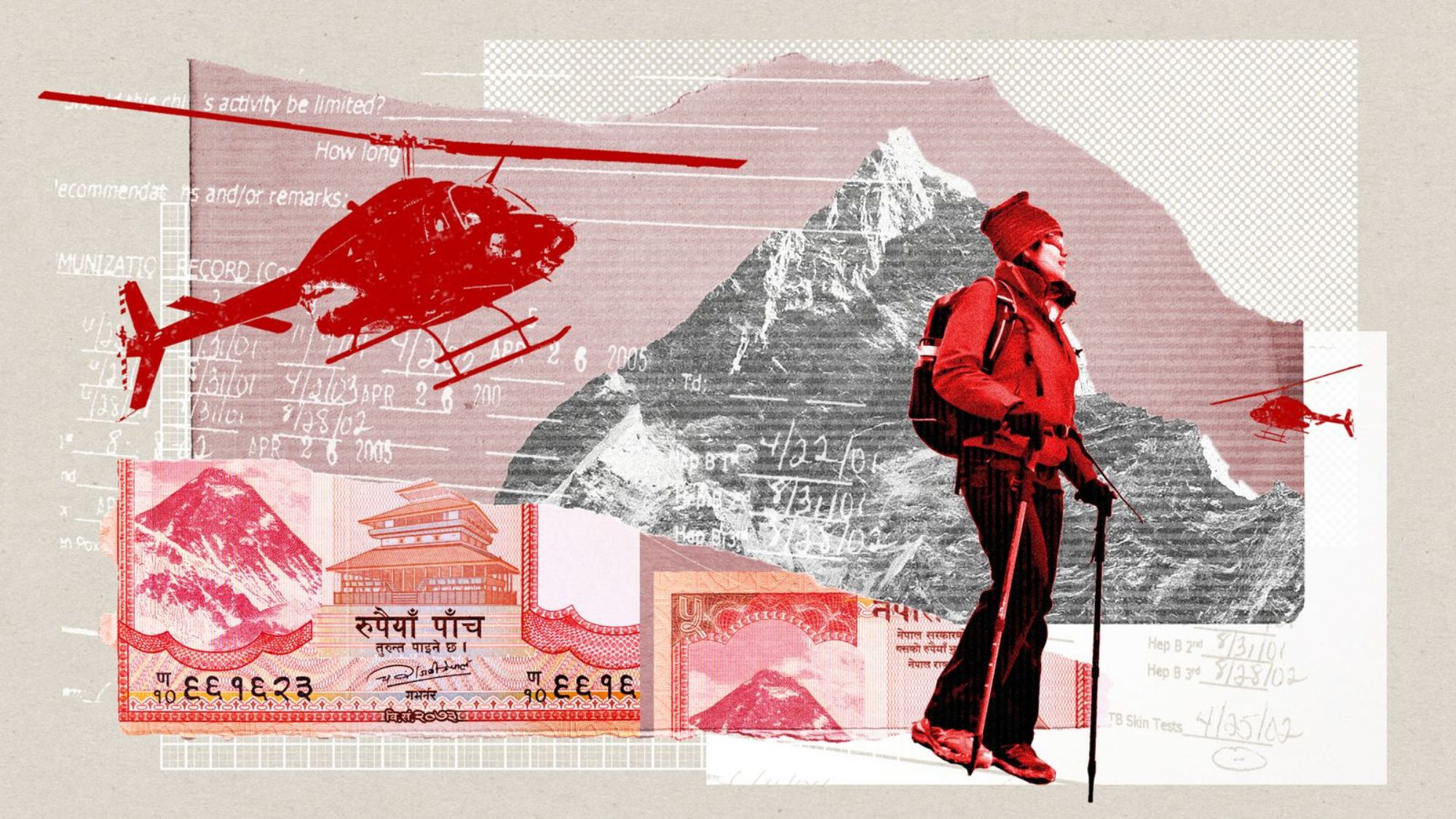

Nepal’s fake mountain rescue fraud

Nepal’s fake mountain rescue fraudUnder The Radar Arrests made in alleged $20 million insurance racket

-

If/Then

feature Tony-winning Idina Menzel “looks and sounds sensational” in a role tailored to her talents.

-

Rocky

feature It’s a wonder that this Rocky ever reaches the top of the steps.

-

Love and Information

feature Leave it to Caryl Churchill to create a play that “so ingeniously mirrors our age of the splintered attention span.”

-

The Bridges of Madison County

feature Jason Robert Brown’s “richly melodic” score is “one of Broadway’s best in the last decade.”

-

Outside Mullingar

feature John Patrick Shanley’s “charmer of a play” isn’t for cynics.

-

The Night Alive

feature Conor McPherson “has a singular gift for making the ordinary glow with an extra dimension.”

-

No Man’s Land

feature The futility of all conversation has been, paradoxically, the subject of “some of the best dialogue ever written.”

-

The Commons of Pensacola

feature Stage and screen actress Amanda Peet's playwriting debut is a “witty and affecting” domestic drama.