The long arm of the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is now recasting itself to combat terrorism. This is but the latest of the fabled bureau’s many incarnations. How did the FBI become the nation’s most powerful law-enforcement agency?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How did the FBI get its start?

It was created on July 26, 1908, during the trust-busting presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s attorney general, Charles J. Bonaparte, felt that to pursue Roosevelt’s progressive agenda, the Justice Department needed its own national crime-fighting unit. But Congress feared that the new body could easily become a secret police force. So when it authorized the new Bureau of Investigation (the “Federal” would be added in 1935), it gave the agency only 34 agents—and forbade them from carrying weapons and making arrests. The BI concentrated at first on antitrust cases, land fraud, and violations of the 1910 Mann Act, which prohibited transporting women across state lines for “immoral purposes.”

How did the bureau gain power?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Following the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia, the Red Scare swept the country. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer ordered the BI to round up hundreds of suspected anarchists and radicals. The “Palmer Raids” violated so many civil liberties, and BI agents grew so violent and corrupt, that in 1924, Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone turned to a 29-year-old BI division head named John Edgar Hoover to clean house.

Did Hoover succeed?

In the early days of his 48-year reign, Hoover brought a new professionalism to the bureau. He introduced the latest scientific advancements in crime detection and deterrence, ranging from the legendary FBI crime lab to the bureau’s fingerprint collection—the largest in the world. By demanding exacting professional standards, Hoover skillfully built up the bureau’s reputation as relentless, efficient, scrupulously honest, and infallible. He reinforced this image with unending public relations efforts—the widely publicized “Ten Most Wanted” list of fugitives, numerous staged arrests featuring Hoover himself, and favorable depictions of the FBI’s heroic agents in Hollywood movies.

What did Hoover actually accomplish?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

His greatest successes came in fighting gangsters, bank robbers, and other conventional outlaws. In the 1930s, the FBI earned national acclaim for killing such notorious figures as John Dillinger, “Pretty Boy” Floyd, and Lester Gillis, aka Baby Face Nelson. When agents captured George “Machine Gun” Kelly, he reportedly cried, “Don’t shoot, G-men!”—presumably short for “government men”—and added a legendary nickname to the American vocabulary. During the Cold War, the FBI turned its attention to counterespionage, unmasking such Soviet agents as Klaus Fuchs, who was convicted of stealing atomic secrets.

Did Hoover go too far?

During the 1950s and ’60s, Hoover became so obsessed with the communist menace that he investigated myriad Americans for “subversive” views and activities, amassing elaborate dossiers containing scurrilous material about their private lives. These efforts culminated with a counterintelligence program called COINTELPRO. Between 1956 and 1971, COINTELPRO operations sought to infiltrate, disrupt, and harass organizations the FBI deemed dangerous. These groups included the Ku Klux Klan, the Black Panthers, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the National Organization for Women. Files were created on thousands of private citizens who criticized the government. In 1975, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Activities said the FBI had engaged in a “vigilante program aimed squarely at preventing the exercise of First Amendment rights of speech and association.” That same year, a Gallup Poll found that only 37 percent of Americans gave the FBI a “highly favorable” rating, down from 84 percent just nine years before.

Has the FBI changed its ways?

After Hoover died in 1972, the FBI became a more conventional law-enforcement agency and focused on a new variety of threats. Whereas Hoover was slow to attack organized crime, today’s FBI has helped break its back, notably with the “Pizza Connection” heroin-trafficking cases of the 1980s. The FBI has also targeted the armed militia movement, and helped nab John A. Walker and Aldrich Ames, who sold classified information to the Soviets. Between 1993 and 1999, the bureau prevented some 40 potentially devastating terrorist attacks on Americans, says Ronald Kessler, author of the book Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. The foiled attacks included al Qaida plots to blow up the United Nations and New York’s Holland and Lincoln tunnels.

Then why is the FBI in trouble?

Because it has also made a series of spectacular mistakes. In 1992, sharpshooters from the FBI and the bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms gunned down the wife and 14-year-old son of the militant separatist Randall Weaver in Ruby Ridge, Idaho. The next year, the bureau attempted to take over the compound of the Branch Davidian cult in Waco, Texas; during the assault, a fire broke out and incinerated more than 80 members of the group. In recent years, the FBI investigated and jailed Chinese-American scientist Wen Ho Lee as an atomic spy, and misplaced more than 4,000 documents in the case of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh.

What about Sept. 11?

The terrorist attacks were, without a doubt, the lowest moment in the FBI’s 93-year history. Several months earlier, agents in two separate FBI offices warned that Islamic extremists might be plotting to hijack U.S. airliners. FBI Director Robert Mueller, who took over the agency a week before Sept. 11, now admits that the bureau missed “red flags” pointing to an al Qaida plot. “Our analytical capability is not where it should be,” Mueller recently told Congress. The bureau created to fight fraud, gangsters and prostitution, he said, needs a new focus. “We need a different approach that puts prevention above all else.”

The G-men vs. the spooks

The FBI’s new focus on counterterrorism means it must work more closely than ever with the Central Intelligence Agency. But the two agencies have a deep and mutual disdain that dates back 60 years. In the 1940s, FBI Director Hoover fought endless turf wars with his old boss William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services, the CIA’s wartime forerunner. The sniping continued for decades; in 1970, Hoover actually ordered that the FBI “have absolutely no contacts with the CIA.” It hasn’t helped that the two cultures are vastly different. The CIA has long been run by Eastern establishment Ivy League graduates who regard the FBI as a glorified, blue-collar police force. The FBI, in turn, considers the CIA a collection of intellectual dilettantes. A 1996 conclave in Rome between all overseas CIA station chiefs and FBI legal attachés pointed up the disparity. “You felt that the CIA guys would be going to the opera after the meeting,” said one observer, “while the FBI guys were going to see the latest shoot-’em-up movie.”

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

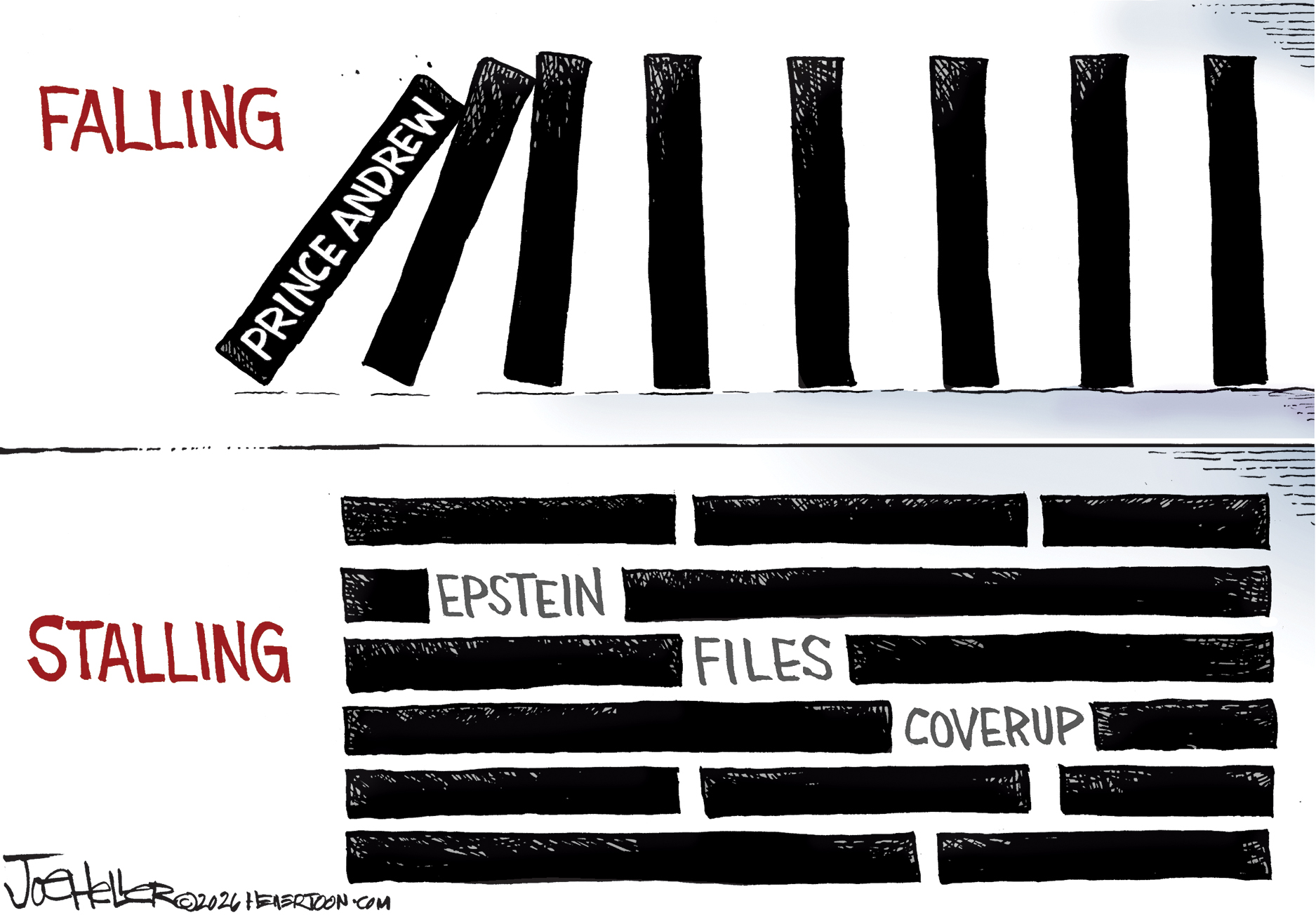

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more