Review of reviews: Books

Book of the week, author of the week, also of interest ... in the uses of power

Review of reviews: Books

Book of the week

The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

By David Halberstam

(Hyperion, $35)

The Korean War, wrote the late David Halberstam, was a conflict in which “almost every key decision on both sides turned on miscalculation.” In mid-1950, North Korea’s Kim Il Sung wrongly assumed that his army could invade South Korea without provoking a sustained U.S. military response. Gen. Douglas MacArthur soon seized an advantage by ordering a daring September landing behind North Korean lines, but incorrectly predicted that American troops could push onward toward North Korea without pulling China into the fight. The eventual July 1953 truce re-established the exact border that divided Korea before the fighting. By then, 33,000 Americans were dead—as were 415,000 of their South Korean allies, 2 million of their Chinese and North Korean counterparts, and 2 million to 3 million civilians.

Providing a fitting cap to a brilliant journalistic career, Halberstam’s final book seems certain “to become the standard one-volume history” of the so-called Forgotten War, said Tim Rutten in the Los Angeles Times. Halberstam finished it just days before a fatal car accident earlier this year, and it’s clear why the 73-year-old Pulitzer Prize winner had been telling friends that The Coldest Winter was his best work yet. Besides its “crystalline portraits” of the drama’s major figures and its incisive account of the conflict’s geopolitical dynamics, the book offers a vivid, grunt’s-eye view of crucial battles fought in a bone-chilling no man’s land. Halberstam interviewed dozens of Americans who saw combat in the war’s crucial early months, and their gruesome, heartbreaking stories underline the hubris and heedlessness of their leaders.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The self-regarding MacArthur, with his phalanx of toadies and penchant for lying to President Harry Truman, easily ranks as the tale’s foremost moral offender, said Stephen Sestanovich in Slate.com. But because Halberstam has a ready villain, he fails to notice that “groupthink,” the ailment of the powerful that he so memorably dissected in The Best and the Brightest, was as much to blame for American blunders in Korea as it was in Vietnam. In many ways, though, this book shows that Halberstam never could get Vietnam out of his mind, said Glenn Garvin in The Miami Herald. Judging from its dour tone, “you might think the Korean War was an American defeat.” If you ask the 49 million citizens of today’s “prosperous and democratic South Korea,” surely they “will tell you otherwise.”

The Billionaire Who Wasn’t: How Chuck Feeney Secretly Made and Gave Away a Fortune

By Conor O’Clery

(PublicAffairs, $26.95)

Chuck Feeney has spent much of the past quarter-century trying to erase his enormous wealth. He has neither a house nor a car. He wears a $15 plastic watch, buys suits off the rack, and wonders sometimes if he really needs more than one pair of shoes. In 1988, when Forbes magazine named him the 23rd richest man in America, the news shocked many of his old friends from working-class Elizabeth, N.J. Up to a point, though, the magazine had its facts right. What reporters didn’t know was that, six years earlier, Feeney had begun transferring much of his wealth to charitable trusts based in Bermuda. He was already on the road to giving it all away.

Feeney, now 76, has been nearly as secretive about his philanthropy as he was about his status as a billionaire, said Michelle Conlin in BusinessWeek. For decades, he made most of his donations anonymously. But he agreed to a biography when he realized his story was leaking out, and Conor O’Clery’s “superbly written page-turner” is the result. Feeney, a Korean War vet who went to Cornell with help from the GI Bill, launched the Duty Free Shoppers retail empire in the late 1950s when he and a partner started selling tariff-free liquor to American sailors stationed in Europe. As they built the business into a worldwide chain of airport concessions, said Jim Dwyer in The New York Times, they took advantage of a gray area of the law and were often “one quick step ahead of police or immigration authorities.”

After the “rollicking” tale of Feeney’s entrepreneurial achievements, said Jonathan Birchall in the Financial Times, our hero is shown devoting “as much energy to giving money away as he did to making it.” The $4 billion that Feeney’s foundations have thus far dispersed have supported AIDS clinics in South Africa, education programs in Vietnam, cancer research in Australia, and peace initiatives in Northern Ireland. But this “complex” man, a well-loved father of five, set the bar high four years ago when his foundation announced that it intended to spend its way out of business by 2017. To do so, said Leslie Lenkowsky in The Wall Street Journal, “it will have to donate at a rate of about a million dollars a day.”

Author of the week

Millard Kaufman

Millard Kaufman offers all 89-year-olds new hope, said Ron Charles in The Washington Post. At 90, the co-creator of the cartoon klutz Mr. Magoo has just published his first novel, and it turns out to be a “brilliant” comic epic that puts him in a class with those relative “young-uns” Kurt Vonnegut and Joseph Heller. Kaufman has a good excuse for withholding his literary talent for so long, said Teddy Wayne in RadarOnline.com. “I’ve been kind of busy making a living writing screenplays,” he says. When the last one, started four years ago, didn’t pan out, Kaufman started writing about a 14-year-old American doctoral candidate awaiting execution in an Iraqi town built entirely of human excrement. Kaufman’s wildly unpredictable picaresque, Bowl of Cherries, was off and running.

Kaufman had plenty of real-world experiences to draw from, said Rebecca Mead in The New Yorker. As a Marine during World War II, he made landings at both Guam and Okinawa. He then used those combat memories to write screenplays for two films—Bad Day at Black Rock and Take the High Ground—that garnered him Oscar nominations in the mid-1950s. One day while Kaufman was working in Italy, Charlie Chaplin taught him an important lesson by walking away from a family day at the beach just as the afternoon sun broke through the clouds. Chaplin explained that unless he wrote every day, he felt as if he didn’t deserve dinner. “That made an impression on me,” says Kaufman. In fact, he’s already working on a second novel.

Also of interest . . . in the uses of power

The Nine

by Jeffrey Toobin

(Doubleday, $27.95)

Jeffrey Toobin’s portrait of today’s Supreme Court reminds me of The New Yorker’s occasional pieces about baseball, said David Margolick in The New York Times. Toobin “writes about the court more fluidly and fluently than anyone” and obviously enjoyed great off-the-record access to three of the justices. But “the game’s been over awhile”; we’ve heard all these stories before.

The Argument

by Matt Bai

(Penguin, $26)

Anyone interested in the future of campaign politics should read this “incisive” and “engaging” account of how liberal bloggers and their deep-pocketed patrons are trying to change the Democratic party, said Jose Antonio Vargas in The Washington Post. But in suggesting that the party lacks a big unifying idea, Matt Bai “misses a big idea himself.” On virtually every issue that gets these activists exercised, all they want is “a government that works.”

The Age of Turbulence

by Alan Greenspan

(Penguin, $35)

The new best-seller by the former Fed chairman is not at all the self-exculpating memoir that news stories made it out to be, said Nicole Gelinas in the New York Post. Its second half is a “journey into the mind” of this accomplished banker and economic thinker. Its first half, better yet, is simply a good story: the tale of how “a hyperanalytic, baseball-obsessed kid” from a tough New York neighborhood grew up to be one of the world’s most powerful men.

Ana’s Story

by Jenna Bush

(HarperCollins, $22)

This nonfiction book for teens from first daughter Jenna Bush is “too earnest for its own good,” said Bob Minzesheimer in USA Today. The story of an HIV-positive teen mother whom the author met while working for UNICEF in Latin America, it may be of some use to American kids “who haven’t thought about what it’s like to be one of the 2.3 million children in the world with HIV or AIDS.” But Ana herself never comes to life, even as we watch her enduring “enough heartbreak to rival Job.”

The Art of Political Murder

by Francisco Goldman

(Grove, $25)

Francisco Goldman’s “finely honed” investigation of a 1998 Guatemalan political execution ventures “deeper than any book has ever gone into the criminal pathologies of contemporary Latin America,” said Roger Atwood in The Boston Globe. By the end of the novelist’s eight-year effort to unravel the conspiracy behind Bishop Juan Gerardi’s death, “his judgment seems to warp a bit.” Still, the truths he finds are “grimly satisfying.”

-

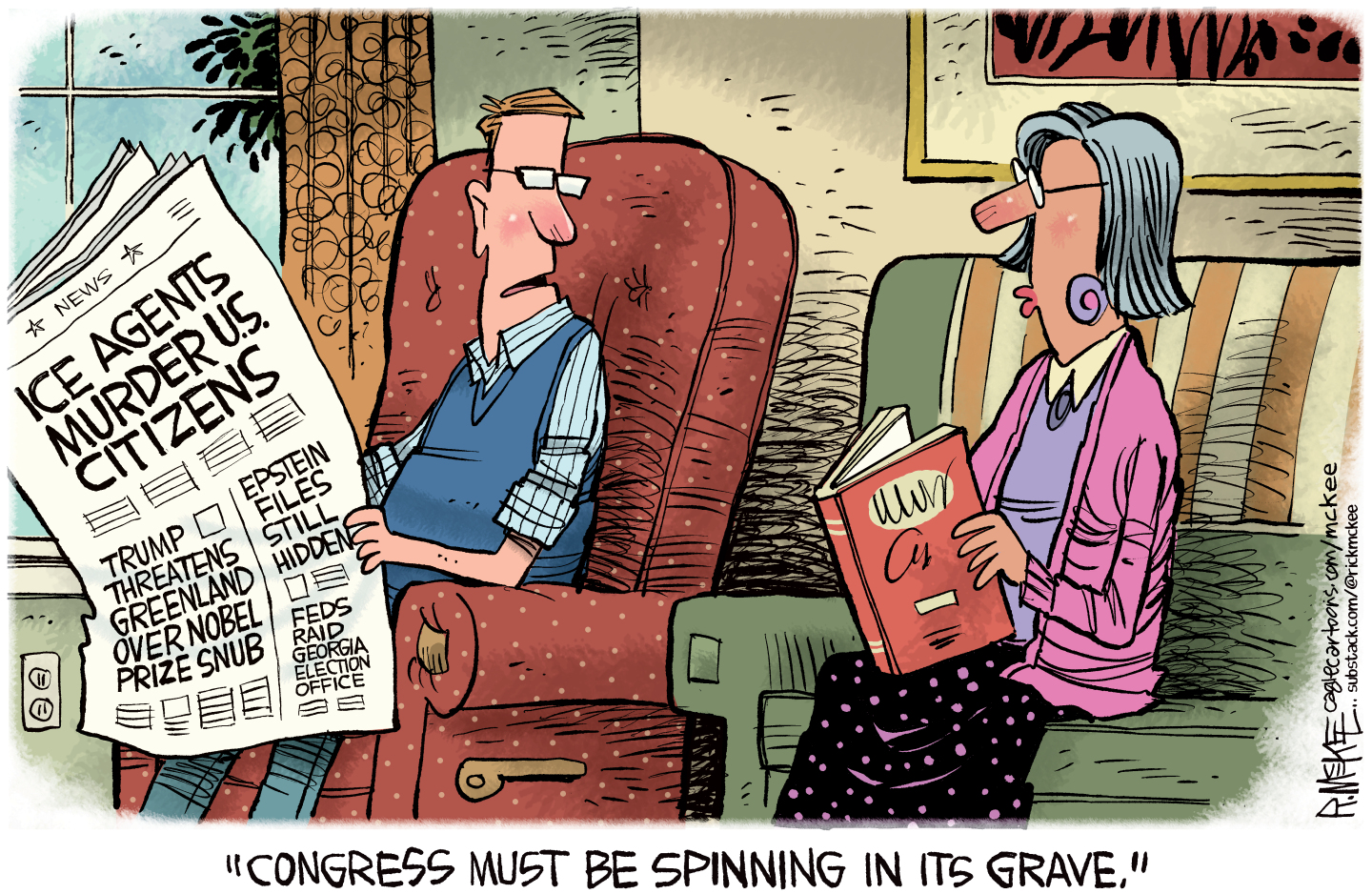

31 political cartoons for January 2026

31 political cartoons for January 2026Cartoons Editorial cartoonists take on Donald Trump, ICE, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Greenland and more

-

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

Also of interest...in picture books for grown-ups

feature How About Never—Is Never Good for You?; The Undertaking of Lily Chen; Meanwhile, in San Francisco; The Portlandia Activity Book

-

Author of the week: Karen Russell

feature Karen Russell could use a rest.

-

The Double Life of Paul de Man by Evelyn Barish

feature Evelyn Barish “has an amazing tale to tell” about the Belgian-born intellectual who enthralled a generation of students and academic colleagues.

-

Book of the week: Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt by Michael Lewis

feature Michael Lewis's description of how high-frequency traders use lightning-fast computers to their advantage is “guaranteed to make blood boil.”

-

Also of interest...in creative rebellion

feature A Man Called Destruction; Rebel Music; American Fun; The Scarlet Sisters

-

Author of the week: Susanna Kaysen

feature For a famous memoirist, Susanna Kaysen is highly ambivalent about sharing details about her life.

-

You Must Remember This: Life and Style in Hollywood’s Golden Age by Robert Wagner

feature Robert Wagner “seems to have known anybody who was anybody in Hollywood.”

-

Book of the week: Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson’s Lost Pacific Empire by Peter Stark

feature The tale of Astoria’s rise and fall turns out to be “as exciting as anything in American history.”